Today, the biggest news comes from Ukraine.

For the first time in this war, Ukrainian forces are matching Russia in one of its most destructive weapons categories: long-range kamikaze drones. Ukraine’s new FP-1 drone is already being produced at a higher rate and is Ukraine’s direct answer to the Russian Shahed drone.

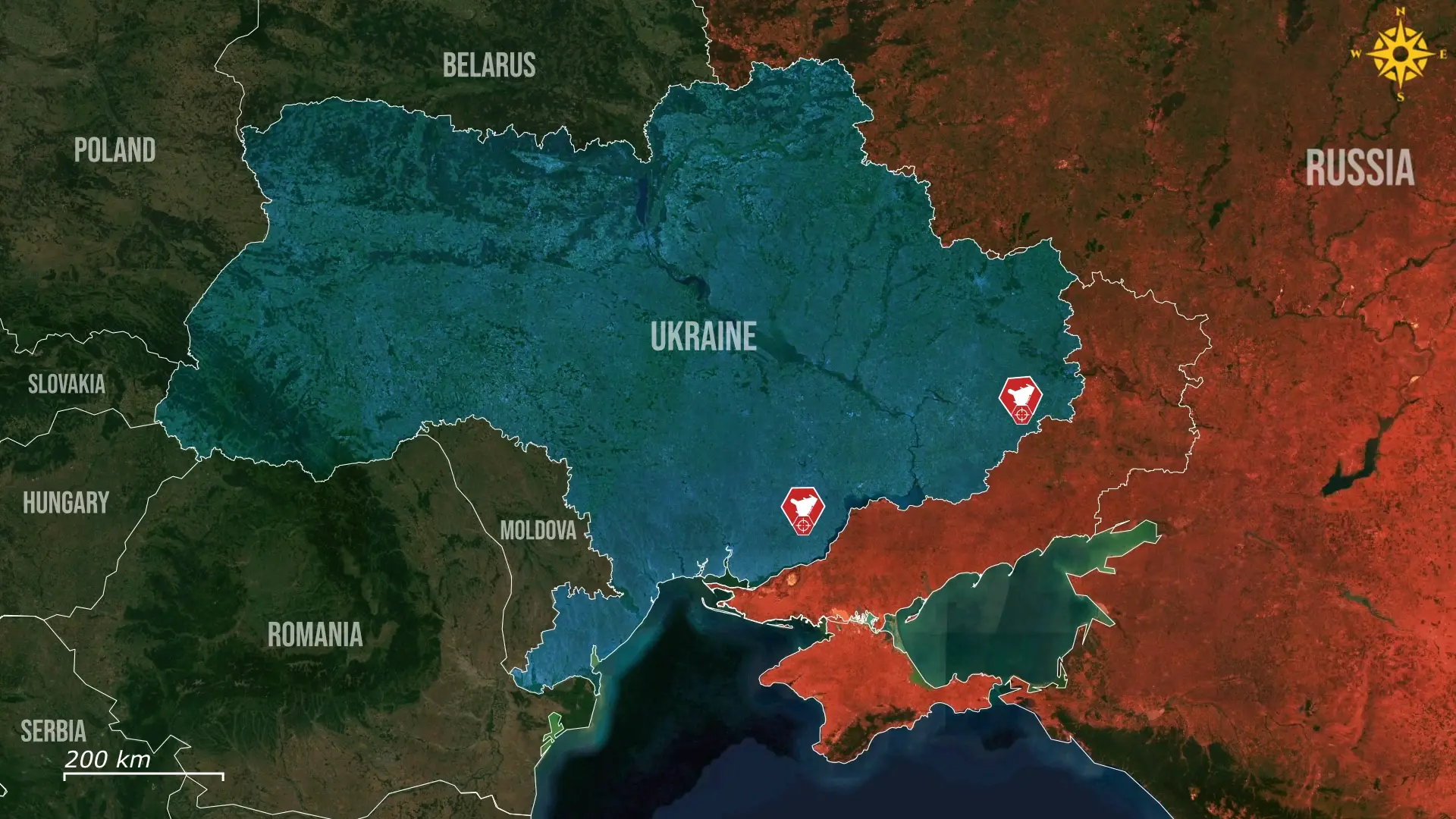

At first glance, the FP-1 looks rudimentary, as its plywood airframe and exposed components seem unsophisticated. However, built for only 55,000 dollars per unit, barely a third the cost of a Shahed, the drone carries a 60-to-120-kilogram warhead, depending on mission profile, and can hit targets up to 1,600 kilometers away, putting not only Crimea but the most major and war-critical Russian logistics hubs in range. Because these drones are built from off-the-shelf parts, their production can be scaled rapidly and put together even under battlefield conditions, allowing for strikes to be launched from positions even near the frontline. It’s easy production process matters because Ukraine’s biggest limitation has been a lack of resources, as it has advanced drones, but not enough to carry out sustained campaigns; the FP-1 changes that. By the end of this year, Ukraine is expected to produce over 3,000 of them per month, rivaling the 2,700 Shaheds that Russia produces each month, without any foreign dependency.

Its advantage lies in numbers and cost, as Russia spends heavily to field a few advanced drones, while Ukraine is betting on fielding thousands of functioning ones, and although the FP-1’s warhead is lighter than a Shahed’s its accuracy and flexibility compensate.

Footage from recent strikes shows Ukrainian drones bypassing static defenses and hitting fuel depots, rail lines, and radar systems, where precision and scale matter than brute force. Compared to earlier Ukrainian efforts like the UJ-22 or Rubaka, the FP-1 is a generational leap, as the UJ-22 had a shorter range and a more complex structure, making rapid production difficult, and the Rubaka had a decent payload but poor navigation.

By contrast, the FP-1 uses inertial and satellite guidance, cruises at 150 to 200 kilometers per hour, and can loiter briefly before impact. That gives Ukraine options: direct strikes, saturation attacks, or baiting out Russian air defenses.

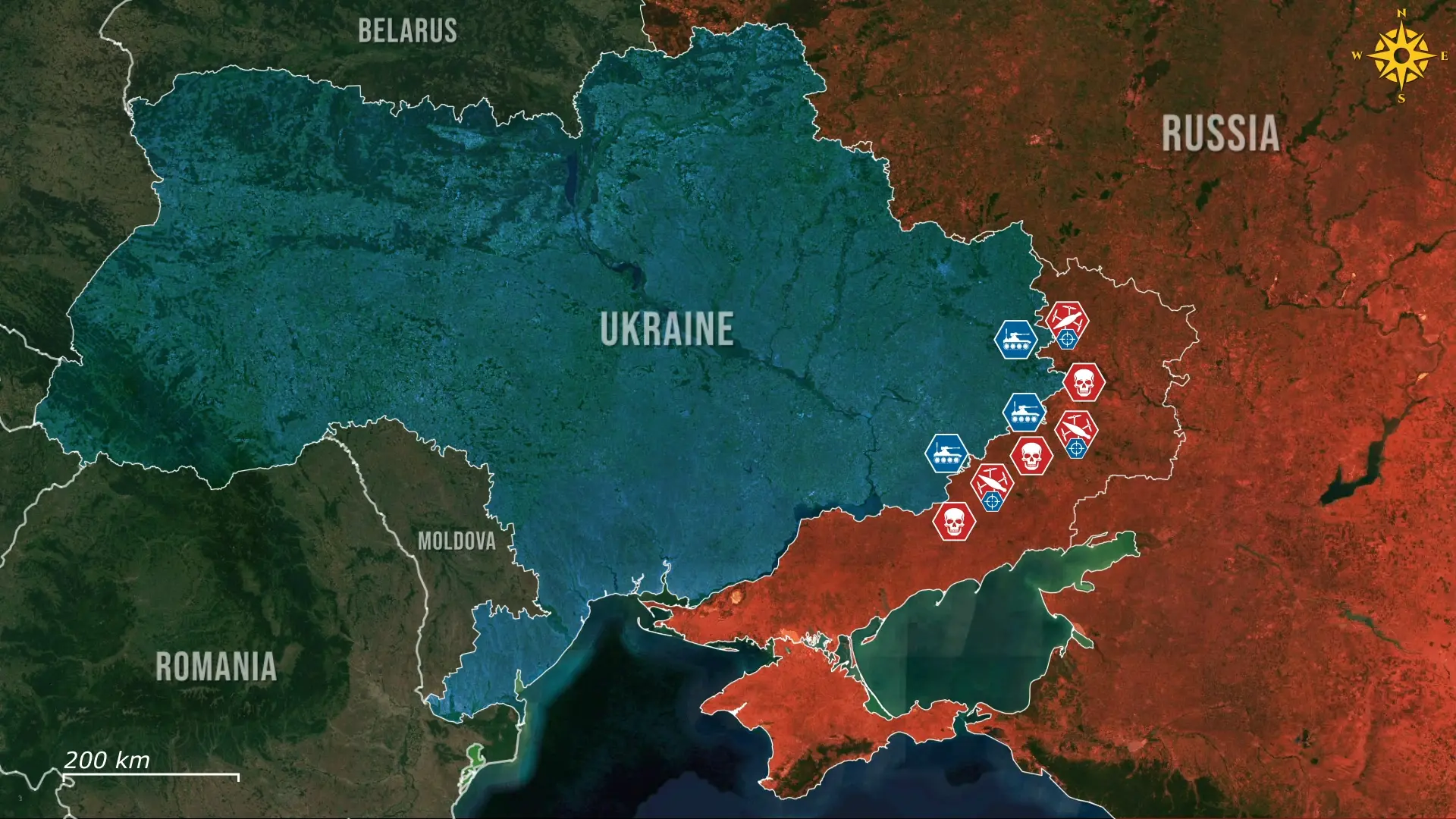

We are already seeing the first signs of this shift, in late August, Ukrainian FP-1s hit a fuel depot in Kursk, a radar station in Bryansk, and an airstrip in Crimea within 48 hours, none of which were previously targeted with such frequency. And unlike Storm Shadows or ATACMS, which are hoarded and only used for high-value targets, the FP-1 is meant to be used in mass.

That changes how Ukraine thinks about targets, because a strike no longer needs to justify the cost of a Western missile or an expensive and advanced drone; it only needs to be worth 55,000 and a few hours on an assembly line.

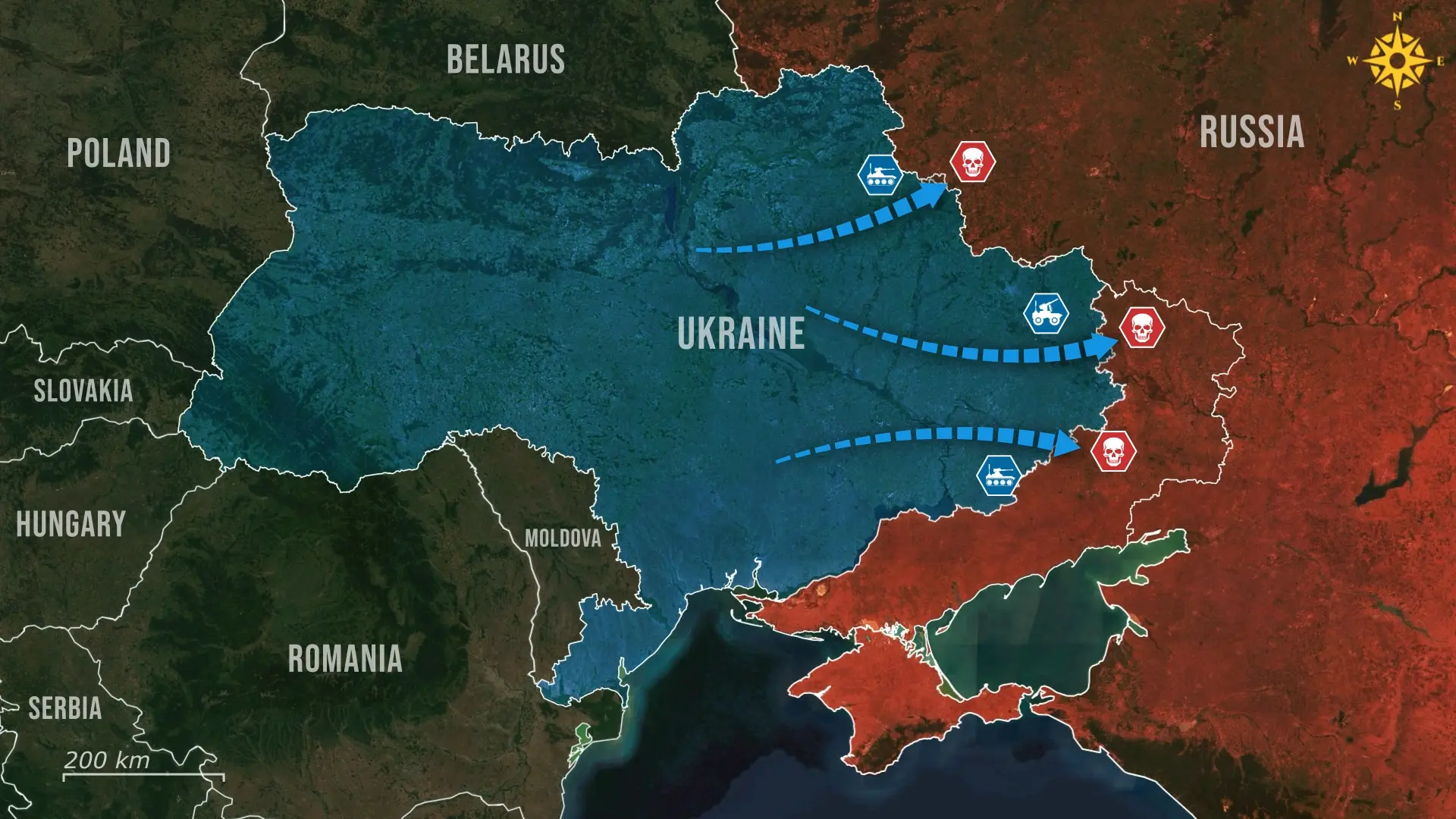

There are still limitations; the FP-1 is vulnerable to electronic warfare and relies on satellite signals that can be jammed. It is noisier and easier to detect than smaller drones, but the point is not invincibility; it is persistence, as one drone can be intercepted, but hundreds launched over a single night cannot. This is how Ukraine intends to wear down Russian air defenses: not through a single breakthrough, but through attrition. And the industrial logic is just as important as the specs, because Ukraine is building a wartime economy, one that can replace losses, scale innovations, and strike across a 1,500 kilometer-wide front as well as deep into the Russian rear. The FP-1 fits into this logic, as it is cheap, modular, and built with Ukrainian labor, in Ukrainian factories, using Ukrainian components

Overall, the FP-1 marks a turning point in Ukraine’s war, as for the first time, Kyiv has the tools to fight a parallel campaign of constant pressure and long-range disruption deep inside Russia. Unlike its Western arsenal, this campaign cannot be paused by a foreign vote or supply issue. Russia’s Shaheds once seemed like an asymmetric advantage, but now they are being met head-on by drones made in Ukraine, flying every night, and hitting harder each time.

.jpg)

Comments