Today, the biggest news comes from the Russian Federation.

Here, after an extensive Ukrainian strike campaign, Russia has been effectively left with no refined fuel for export, as export flows of petrol and diesel have collapsed toward levels last seen during the pandemic, and the economy is beginning to feel a systemic supply crisis rather than a brief disruption. Trains and tankers that once delivered refined product reliably are now moving far less, and that shortfall is already visible at pumps, on ship manifests, and in ministry briefings.

Daily rail shipments of crude and refined fuel fell in September back to levels last seen in 2020, at the beginning of the pandemic collapse. Daily rail loading of crude and finished fuel fell to 3,690,000 barrels per day in September, a level last seen in June 2020. This reflects a massive drop of over 26% compared to the Russian average last year. So, where long strings of tank cars were once left at terminals routinely, rail moves far fewer products, and there are many fewer products available to feed export ships.

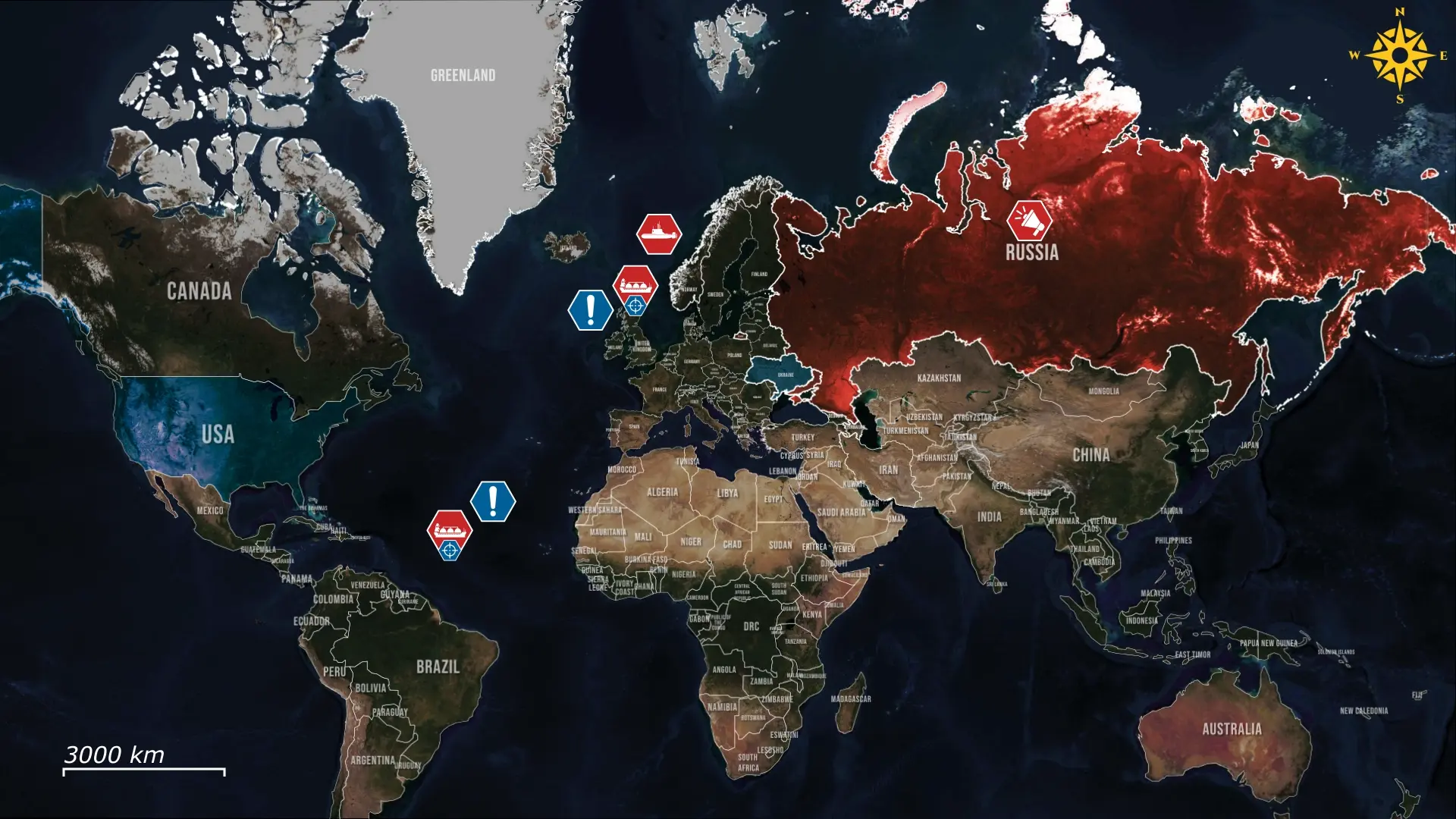

At the sea, the picture is also bad; seaborne exports of refined products dropped about 17 percent in September after strikes forced several big refineries to halt processing. When ports and ship calls become unreliable, insurers raise premiums or restrict cover for voyages, especially older shadow fleet tankers that sail with unclear documentation. That forces traders to hunt for scarce, more expensive insurance or switch to lower-quality vessels with thin or state-backed cover, delaying shipments and raising the cost of every barrel that moves. In practice, rising insurance and freight costs both squeeze buyers and make some trades uneconomic. The total drop equals 153 million barrels lost in September, causing a revenue drop of over 12 billion US dollars in one month alone.

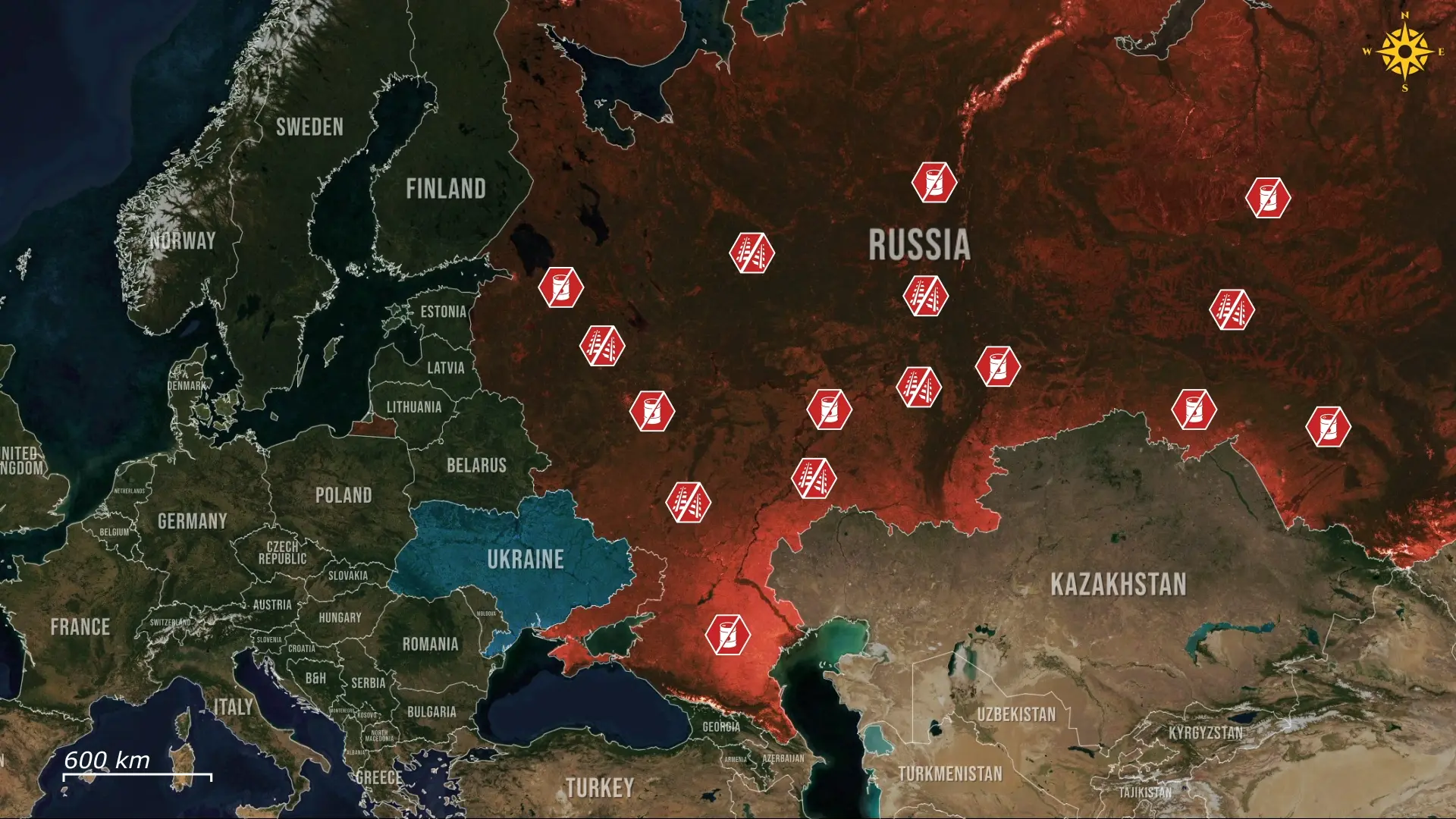

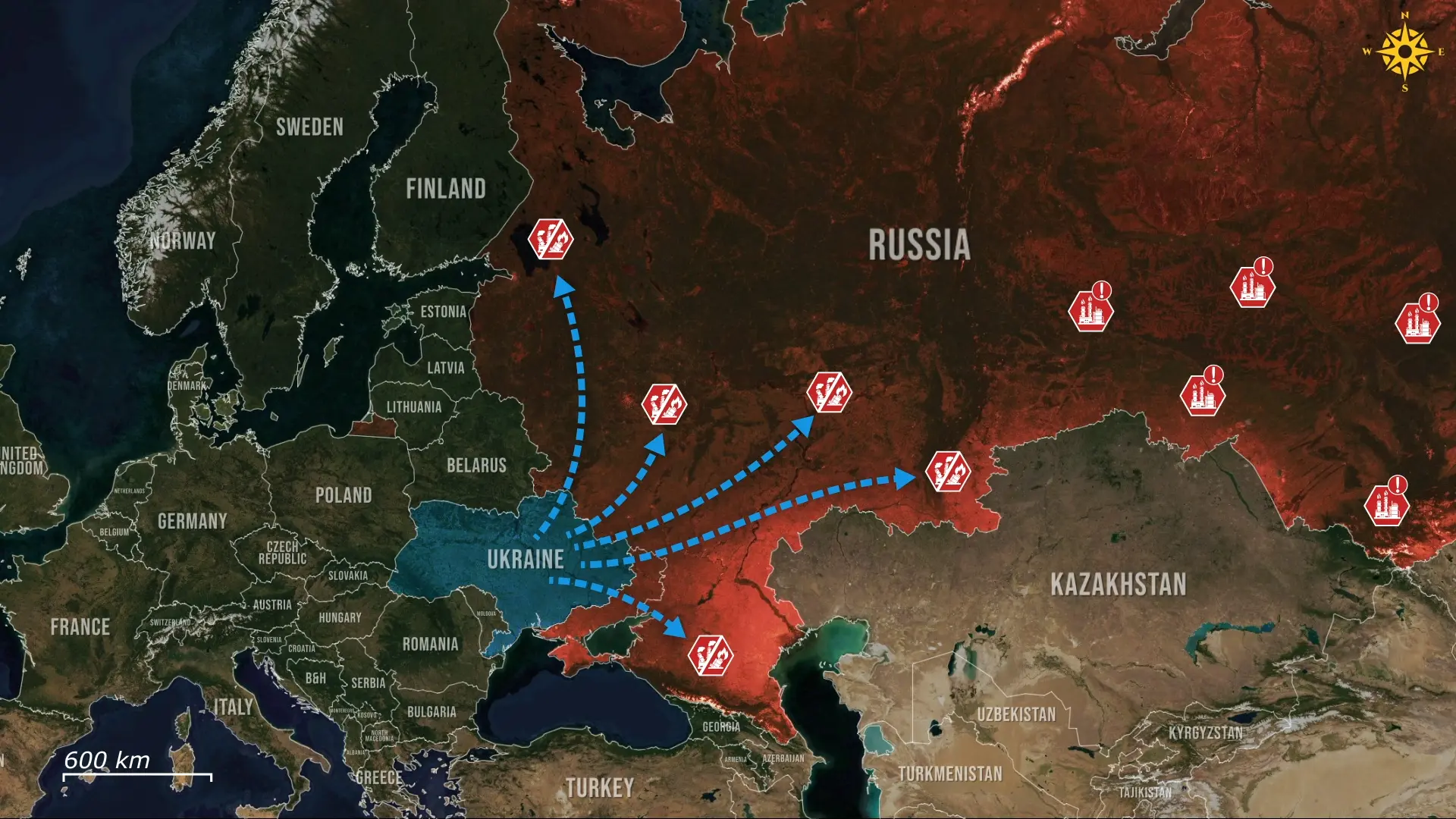

The reason this is happening is that about half of Russia’s refineries have been hit or forced to stop work after repeated Ukrainian drone strikes, leaving far less fuel to ship out. The remaining half are either too far from Ukraine to be immediately threatened or are already running at reduced output or strained production, because spare parts and specialist repair crews are difficult to obtain under sanctions, with the few Russia does have available often being rerouted to repair the destroyed facilities instead. That means even undamaged refineries cannot make up that shortfall to a necessary level.

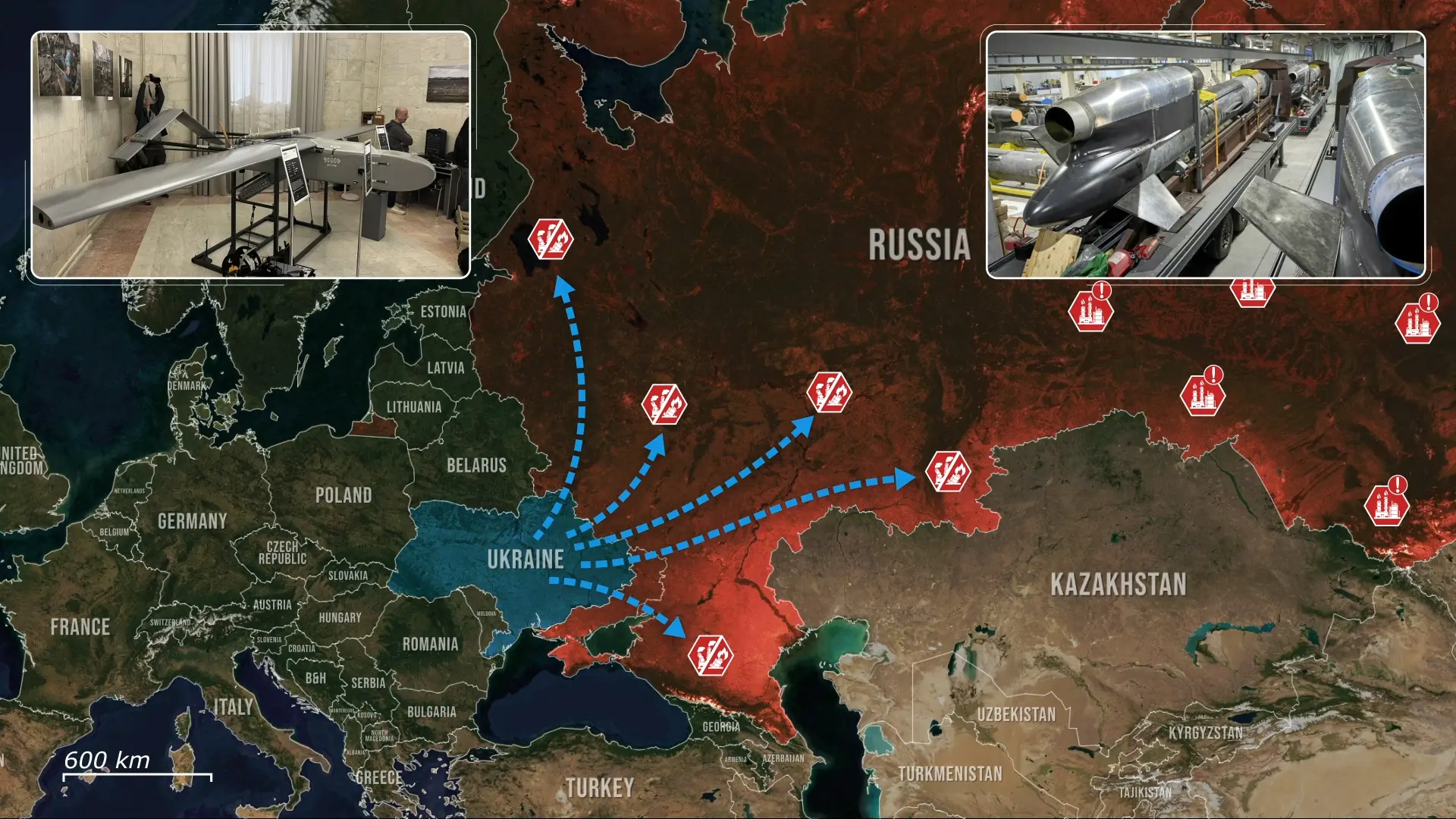

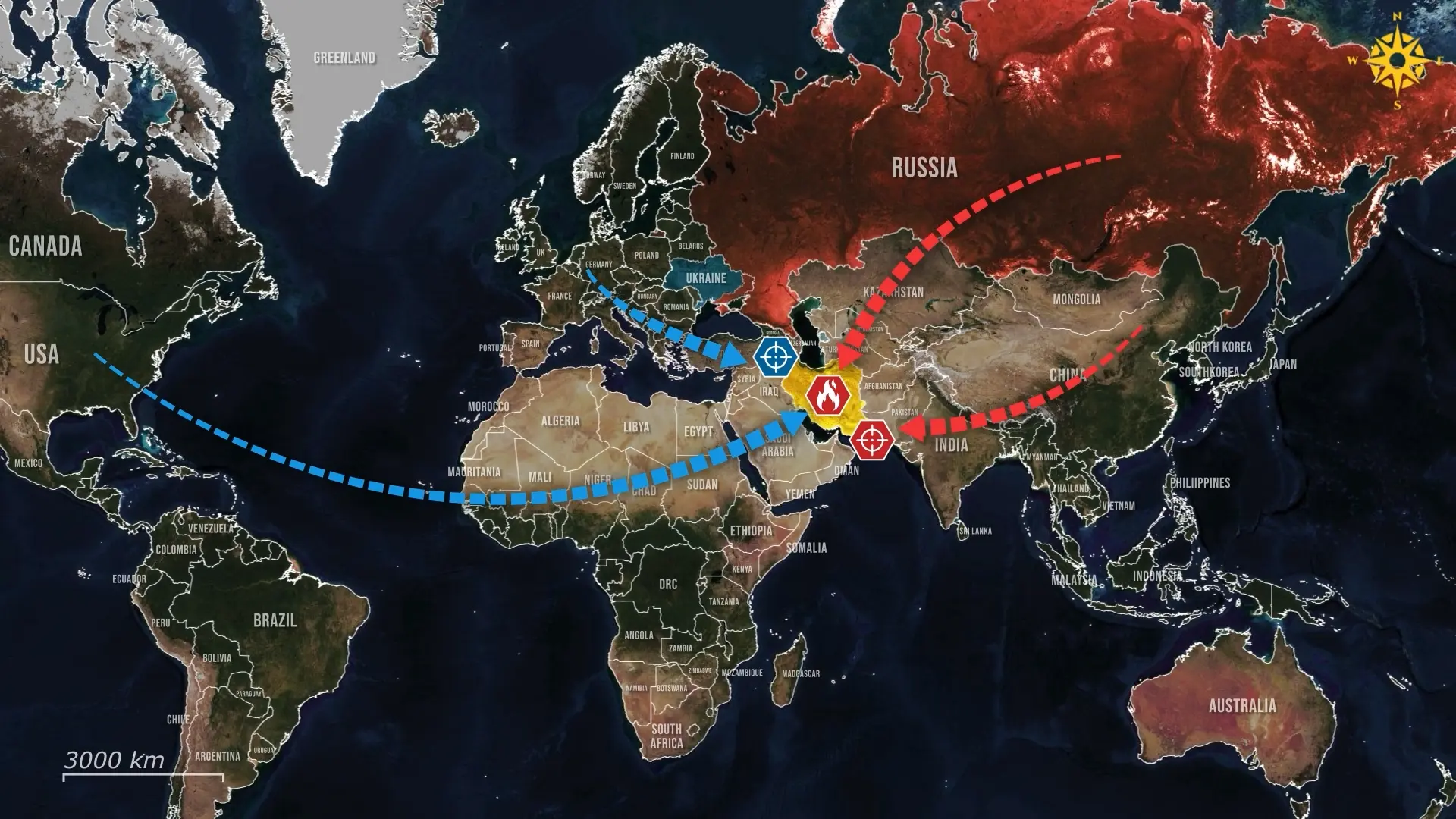

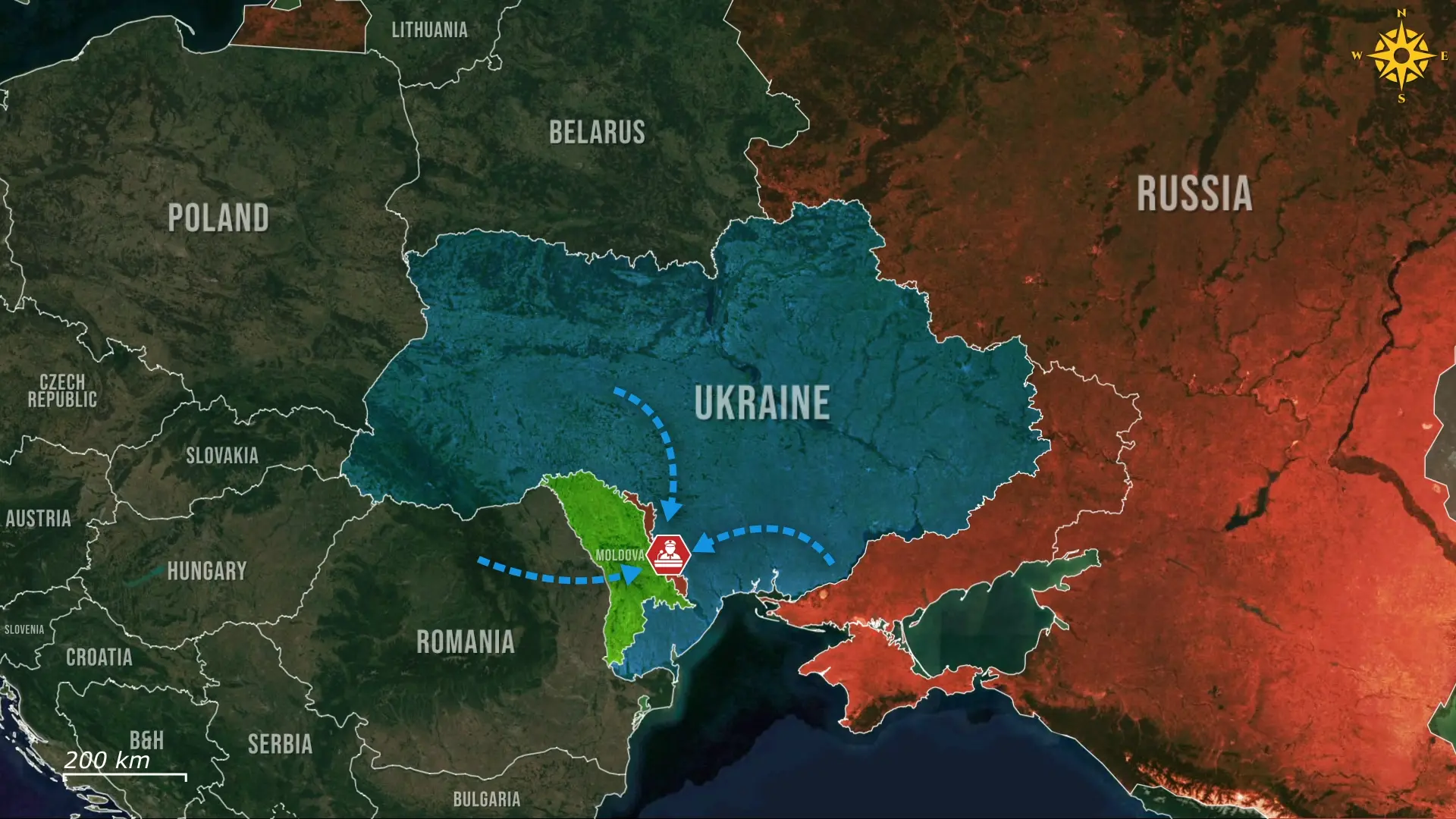

Ukraine’s expanded arsenal of long-range strike weapons is part of the reason, domestically produced and with impressive ranges. Ukraine’s FP-1 drones are responsible for 60 percent of the strikes, with a range of 1,600 kilometers and a 60 to 120 kilogram warhead, precise and powerful enough to cripple refinery modules. Notably, some reports indicate that Ukraine might have even used its new Flamingo cruise missiles to conduct some of the strikes on refineries, which, if true, would have caused much more devastating damage as a result.

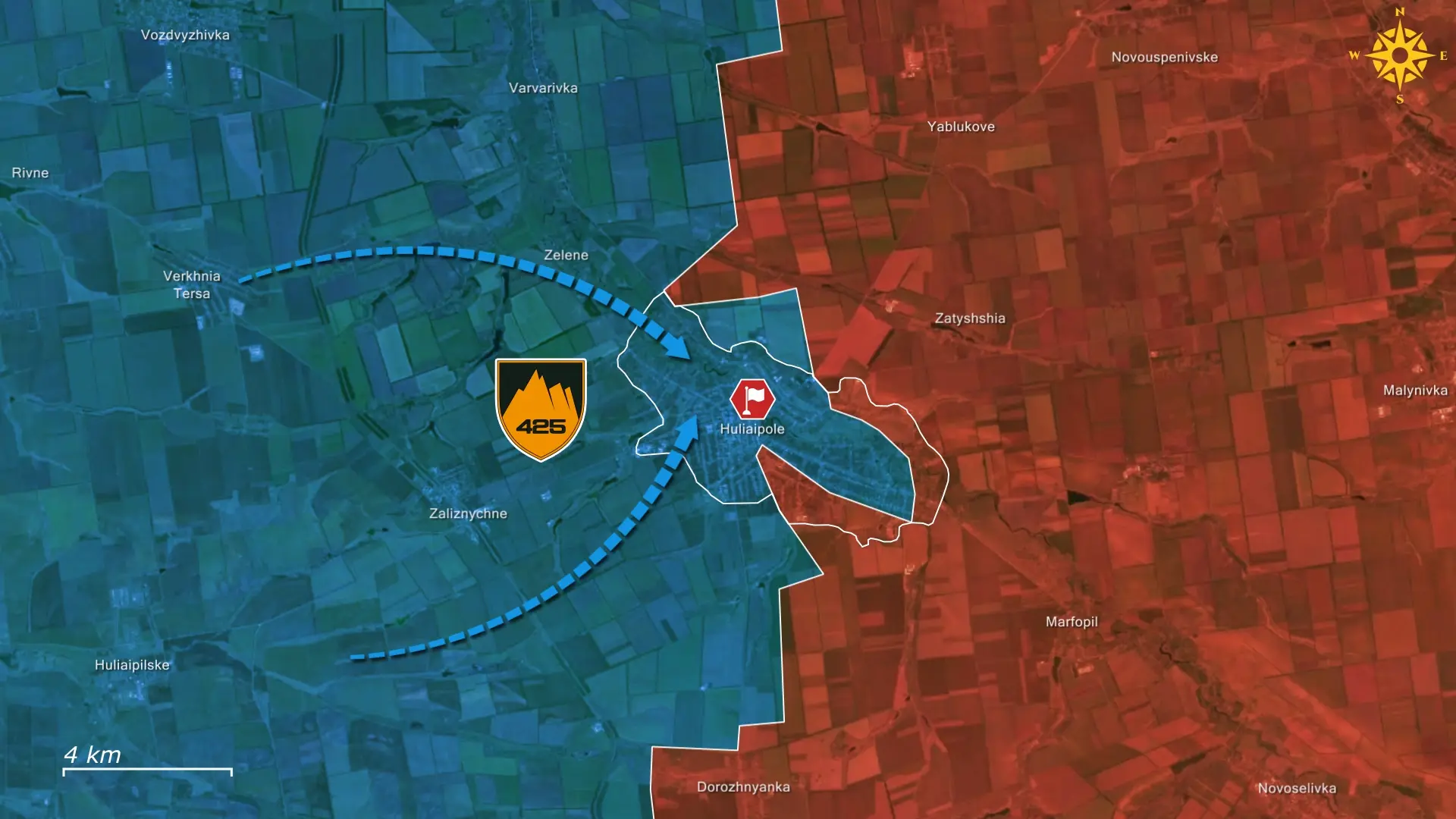

With Russia’s refineries out of action, depots have now become prime targets, where fuel waits before being loaded onto ships or trains. Footage and satellite images show large depot fires and damaged rail-storage sites.

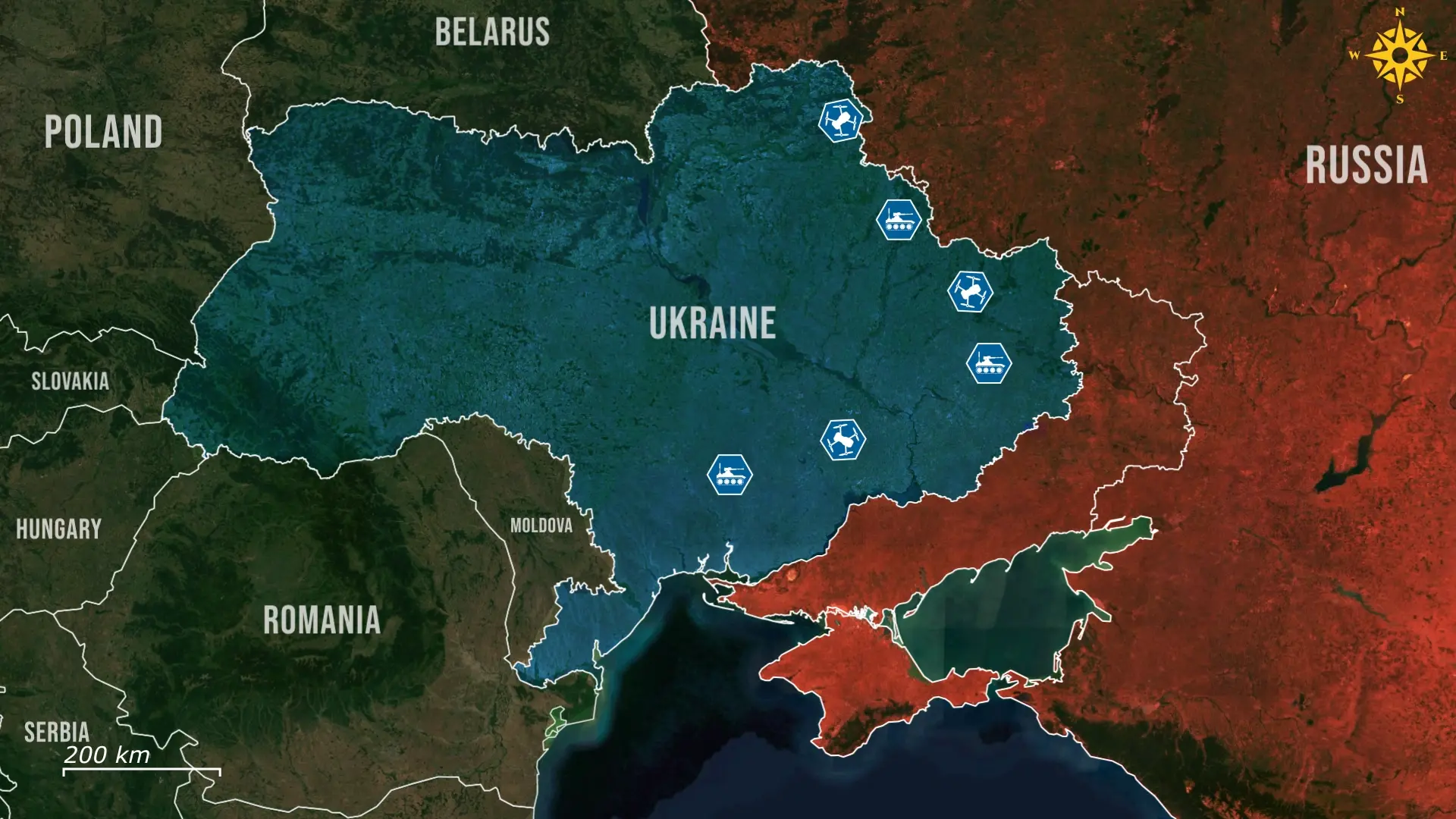

When those storage pools burn or are taken offline, producers cannot hold product for export or route it around damaged plants, so exports drop further, and local markets run out faster. Hitting depots is a simple and brutal way to widen the crisis while refineries are being repaired, offering valuable targets in the meantime while Ukraine waits to strike refineries again. The knock-on effects are immediate and easy to understand, as people and businesses face shortages and rationing, while even army units are suffering from low supplies.

Overall, damaged refineries, depot fires, and collapsed rail loading have combined to push Russia’s fuel system towards a crisis similar in scale to the pandemic shock. Fixing refineries takes weeks or months because parts and skilled crews are scarce, and every depot hit removes the buffers that would otherwise keep exports flowing. If pressure on both processing and storage continues, Moscow will face three bad choices: spend heavily to import refined fuel, accept long-term export losses, or ration supplies at home, none of which are quick or painless fixes.

.jpg)

Comments