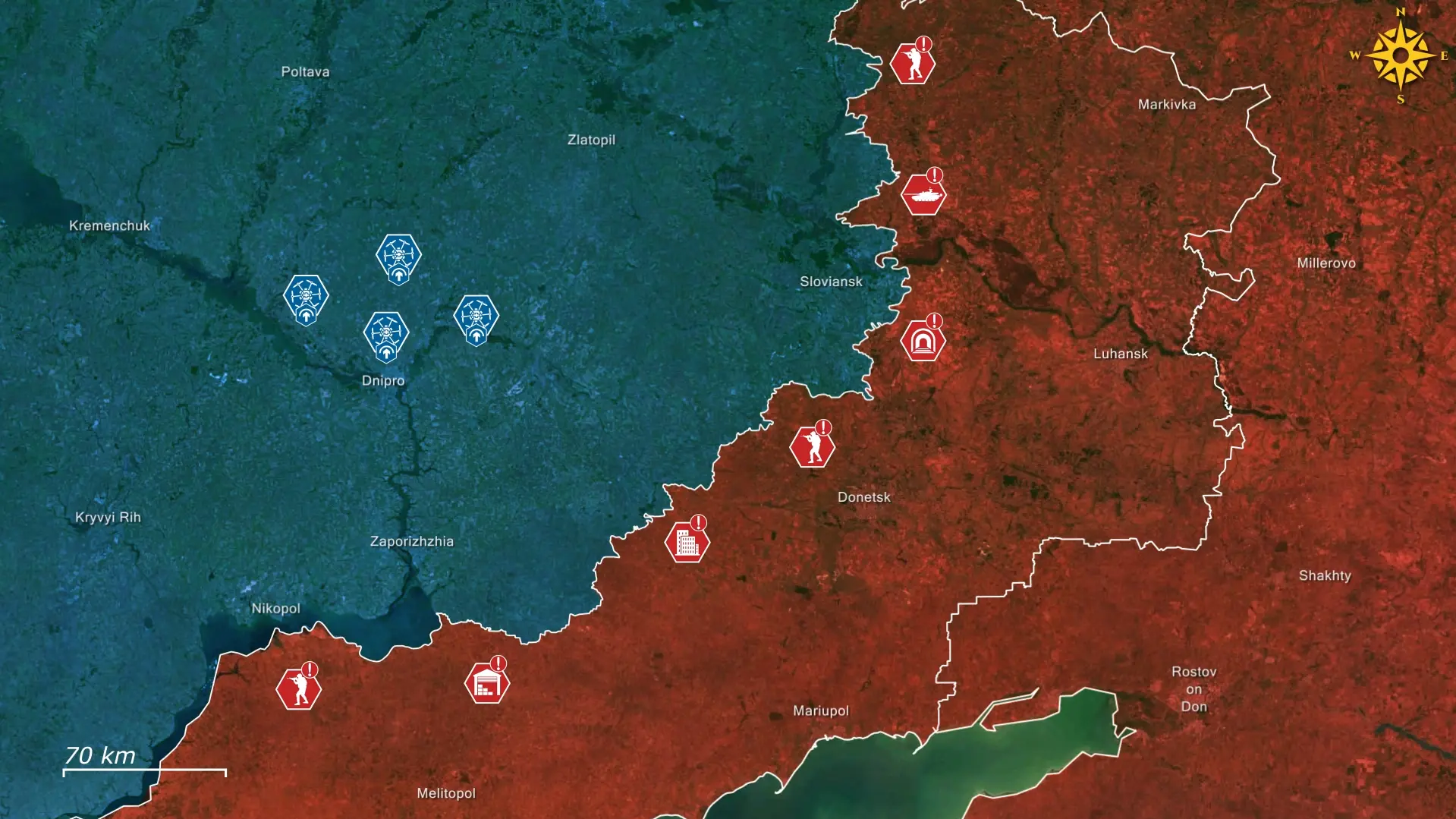

Today, the biggest news comes from the Black Sea.

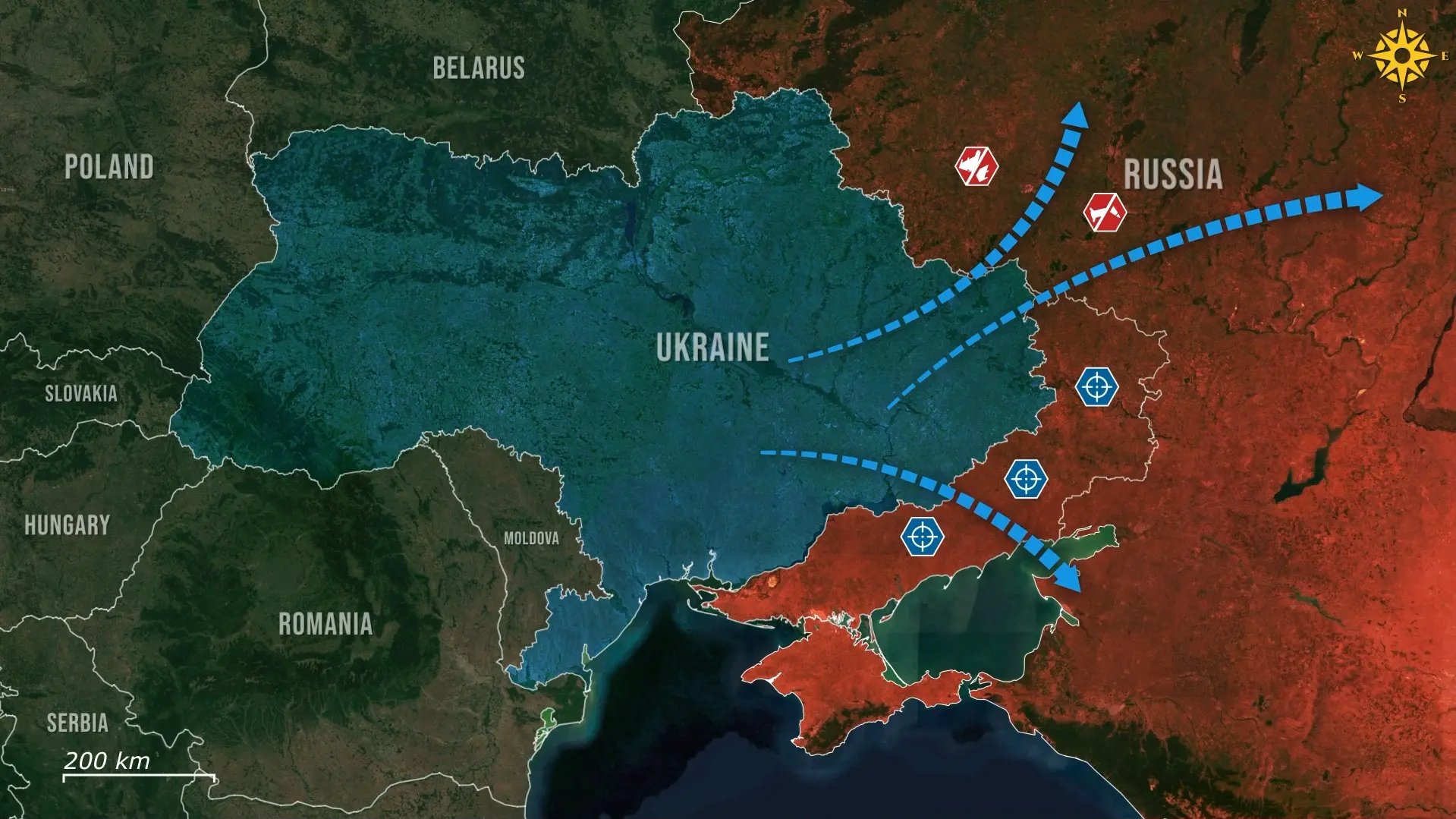

Here, Ukrainian naval drones have forced Russia’s shadow fleet tankers to scatter, halt, or divert, leaving major Russian ports without a single tanker to export their oil. For the first time, Russia’s maritime loophole around sanctions is being hit faster than it can recover, and the window for shadow-fleet operations is narrowing at an unprecedented speed.

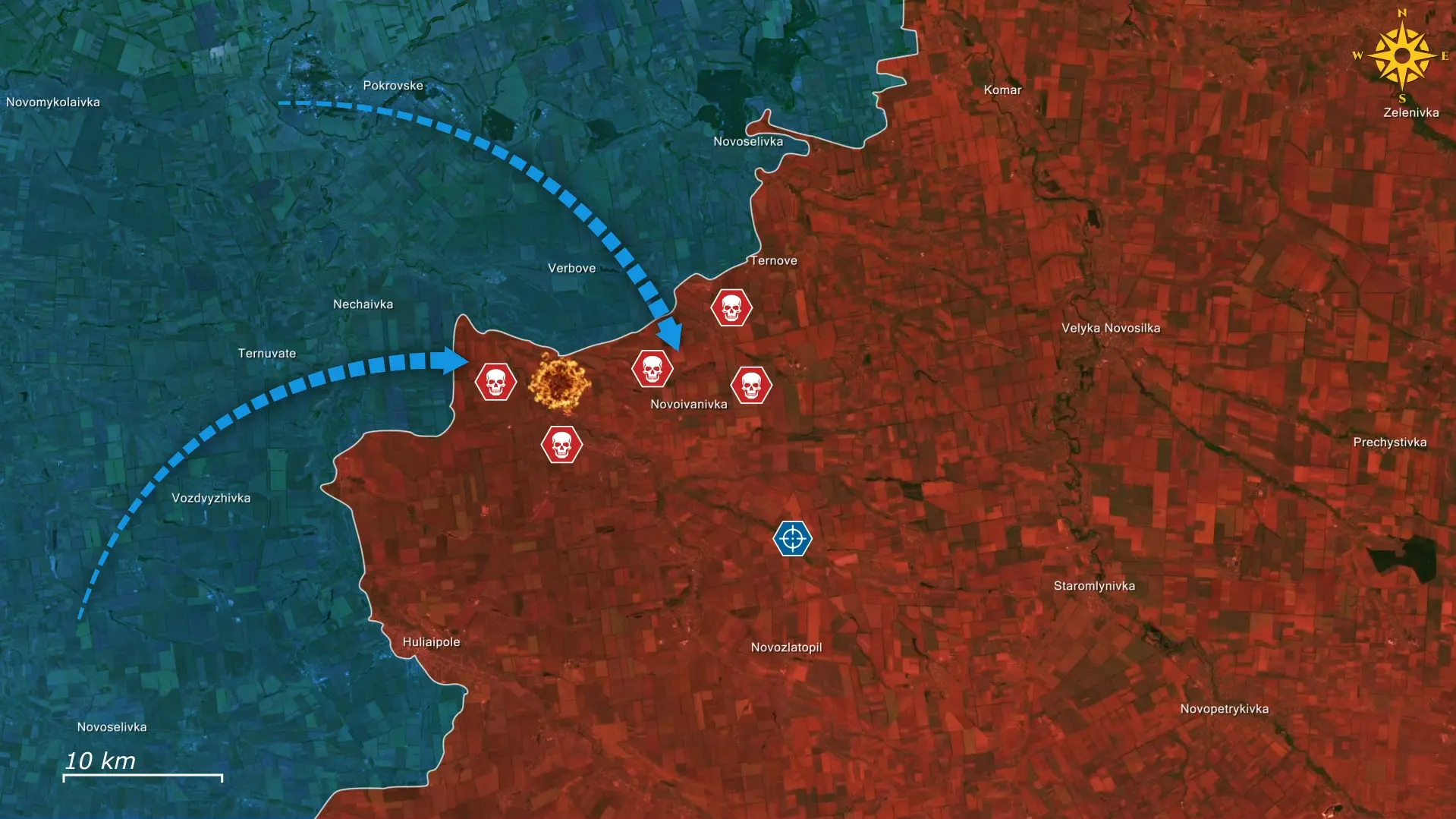

The recent naval drone strikes on the tankers Kairos and Virat set the tone, as both vessels were empty and heading for the major port of Novorossiysk for resupply when Sea Baby drones hit their engine rooms, forcing evacuation and leaving the ships burning.

Tracking data afterward showed tankers loitering offshore from Novorossiysk, holding position rather than entering port, and Russian economists warned that the real danger now comes from insurers. If Insurers refuse coverage and vessel owners decline to lease their ships into a war zone, Russia could lose access to a large share of the five hundred tankers it uses to move sanctioned oil. Roughly half of the shadow fleet consists of foreign-owned vessels that Russia leases, meaning those ships could disappear from its logistics chain if owners pull out, a prospect that Russian economists now describe as the most severe outcome of Ukraine’s maritime campaign.

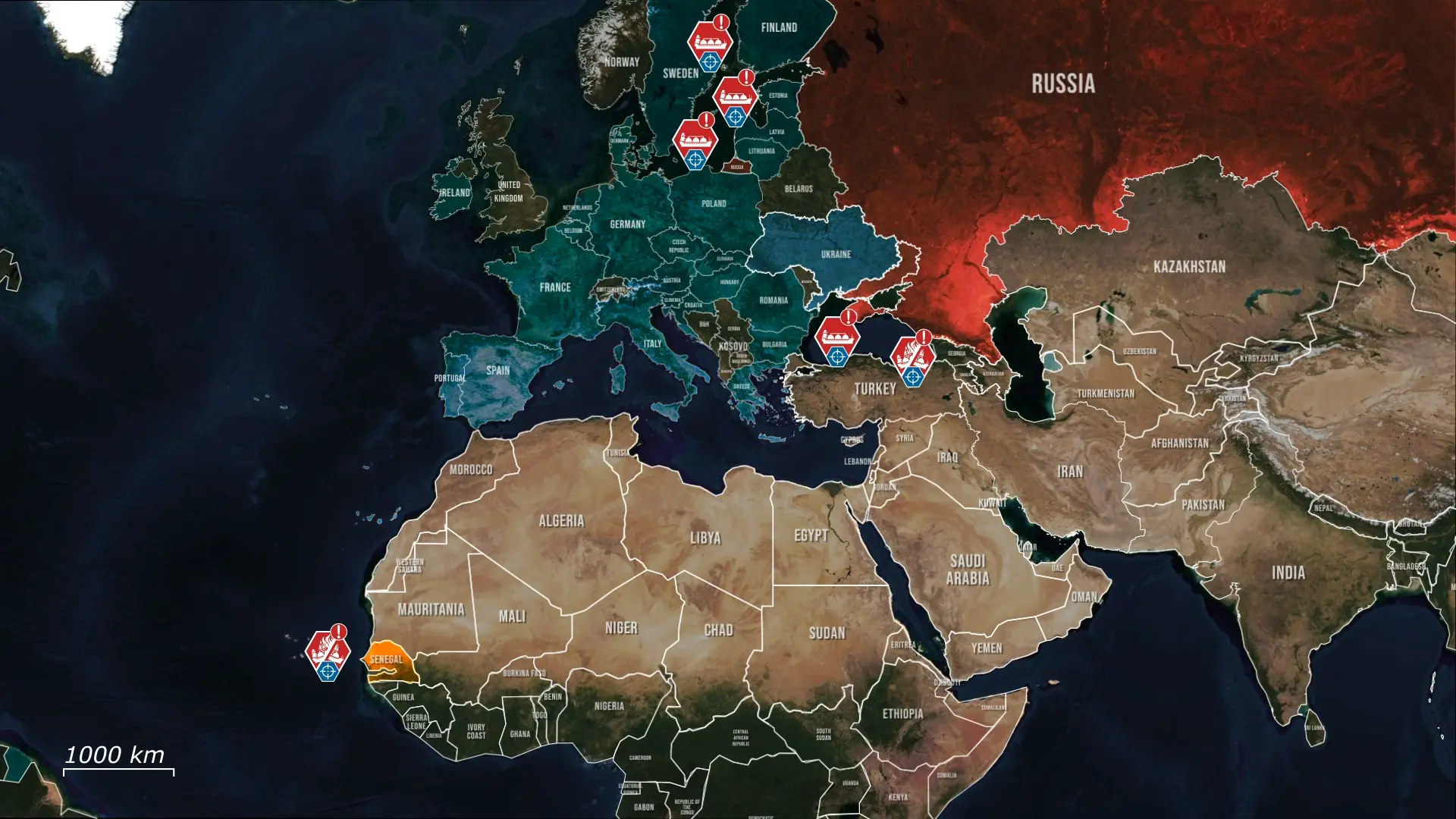

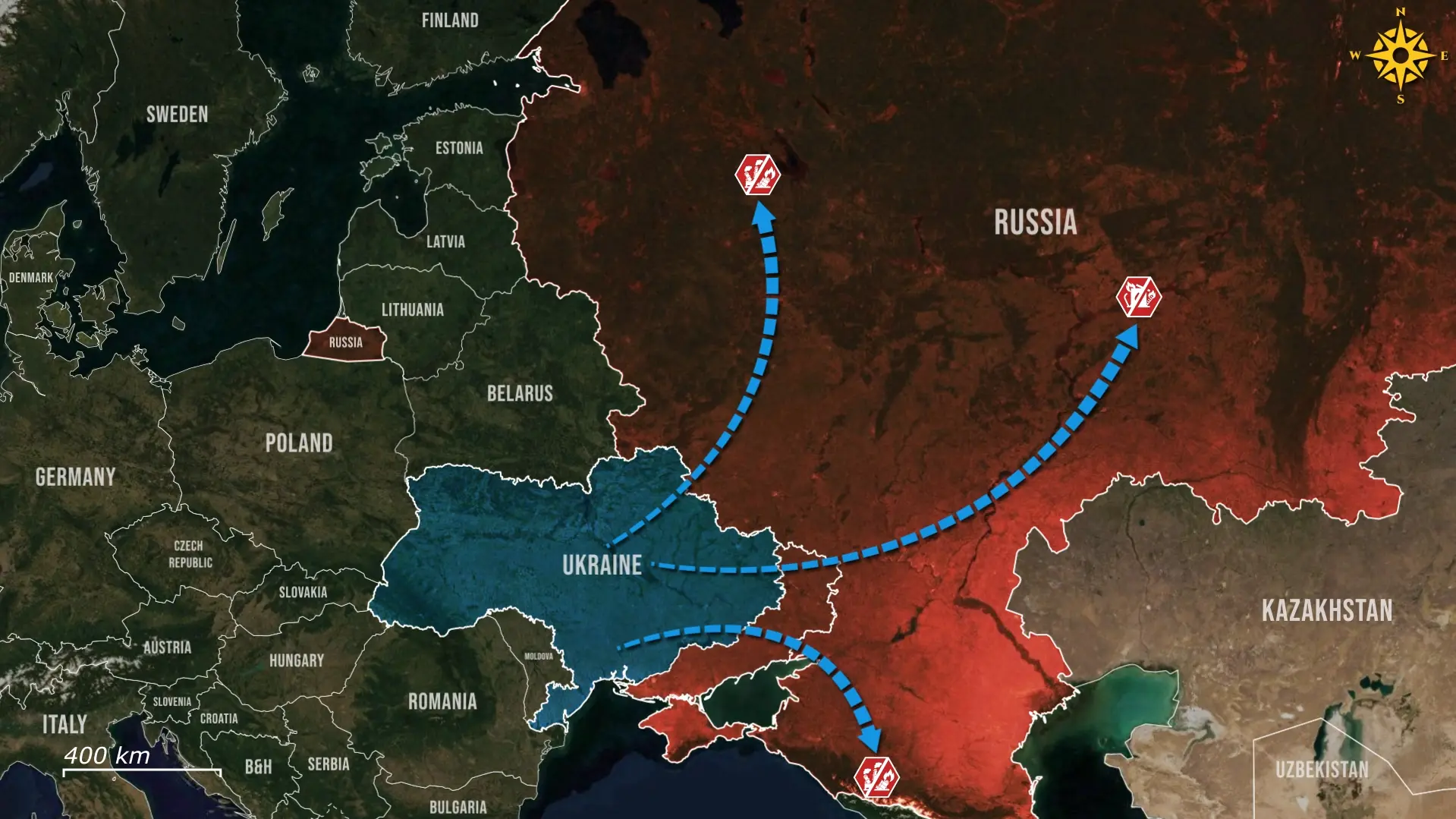

Now the pattern appears to be extending beyond the Black Sea, as off the coast of Senegal, the tanker Mersin is sinking after an explosion caused by an internal explosion. The vessel frequently visited Novorossiysk and Taman, making it a target for Ukrainian tracking of Russian-linked maritime logistics. The Mersin incident joins earlier attacks on the tanker Sig near Crimea, several strikes on vessels moving crude towards Asia, and multiple close calls along the Bosporus Corridor. Each case is different, but together they point to a strategy that follows Russian oil routes rather than staying confined to the regional theatre. This possibility is now openly discussed in Russian channels, which warn that any vessel tied to sanctioned exports may be at risk regardless of where it sails.

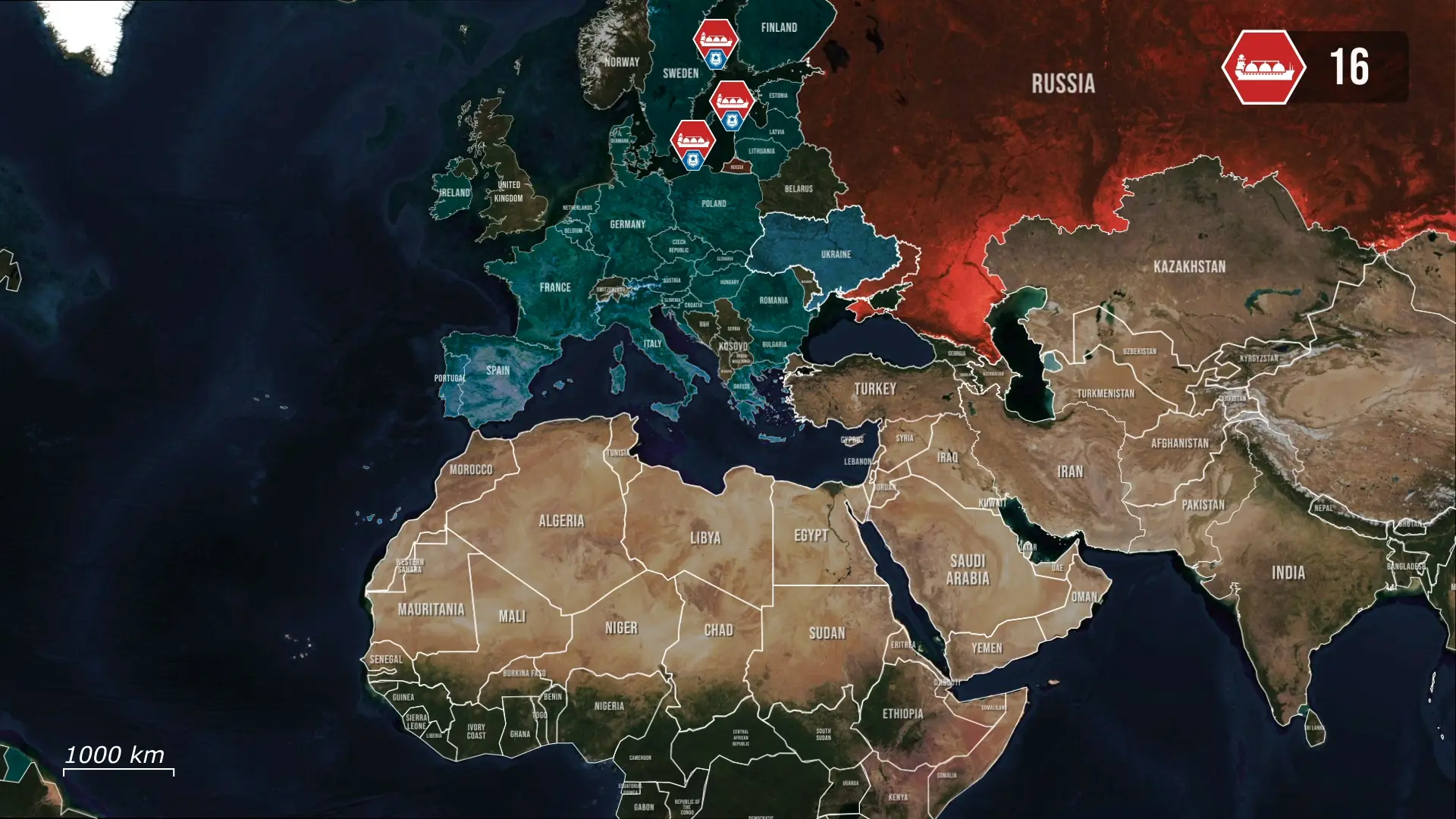

Meanwhile, Europe is moving to close the Baltic Sea to shadow-fleet traffic, after Moscow rejected key elements of the latest U.S. proposal, Washington signaled harsher sanctions that would expand liability for companies enabling Russian oil shipments. Brussels is acting as well, as the EU is preparing legal grounds to intercept all stateless or unflagged tankers under Article 110 of the UN Convention, shifting from the previous approach, which limited interception to only clear embargo violations. At least sixteen vessels fall under the new criteria immediately, and additional tankers may be blacklisted in the next sanctions package. This changes the operating environment in the Baltic, because European coast guards would gain authority to stop, inspect, and detain all Russian-linked tankers in international waters, mirroring the pressure Ukraine has created in the Black Sea.

European governments are also focused on a security threat that goes beyond oil, as on the front, FPV drones regularly travel forty kilometers, and Iran has shown that Shahed-type drones can be launched from containers mounted on civilian ships. Intelligence assessments warn that Russia could attempt a similar launch platform at sea, using the shadow fleet as a covert threat against European ports, energy facilities, or airport infrastructure.

Shadow-fleet vessels already operate with minimal oversight, often with murky ownership and inconsistent identification. This leaves room for maritime activity in a crisis, and European states are moving to close it early. The tightening of Baltic rules is therefore motivated by both sanctions enforcement and the desire to shut down a possible maritime drone threat, with Ukraine’s recent strikes adding urgency.

Overall, the pressure on Russia’s shadow fleet marks a turning point in the maritime phase of the war. Ukraine has turned the Black Sea into a high-risk zone for Russian oil shipping, leaving tankers stalled offshore and insurers unwilling to absorb the danger. Incidents near Senegal suggest that the threat now follows Russia’s global oil routes rather than remaining regional, while Europe is building the legal and security framework to restrict shadow-fleet movement in the Baltic. Russia built this network to evade sanctions and keep its oil revenue flowing, but with ships burning, insurers retreating, and enforcement tightening from several directions at once, the system that once protected Moscow’s exports is beginning to collapse under sustained pressure.

.jpg)

Comments