Recently, a strike on Russia’s Flamingo naval base in Port Sudan has pulled the Red Sea deeper into Sudan’s civil war. What was once a quiet military base is now exposed, contested, and central to a much larger regional power struggle.

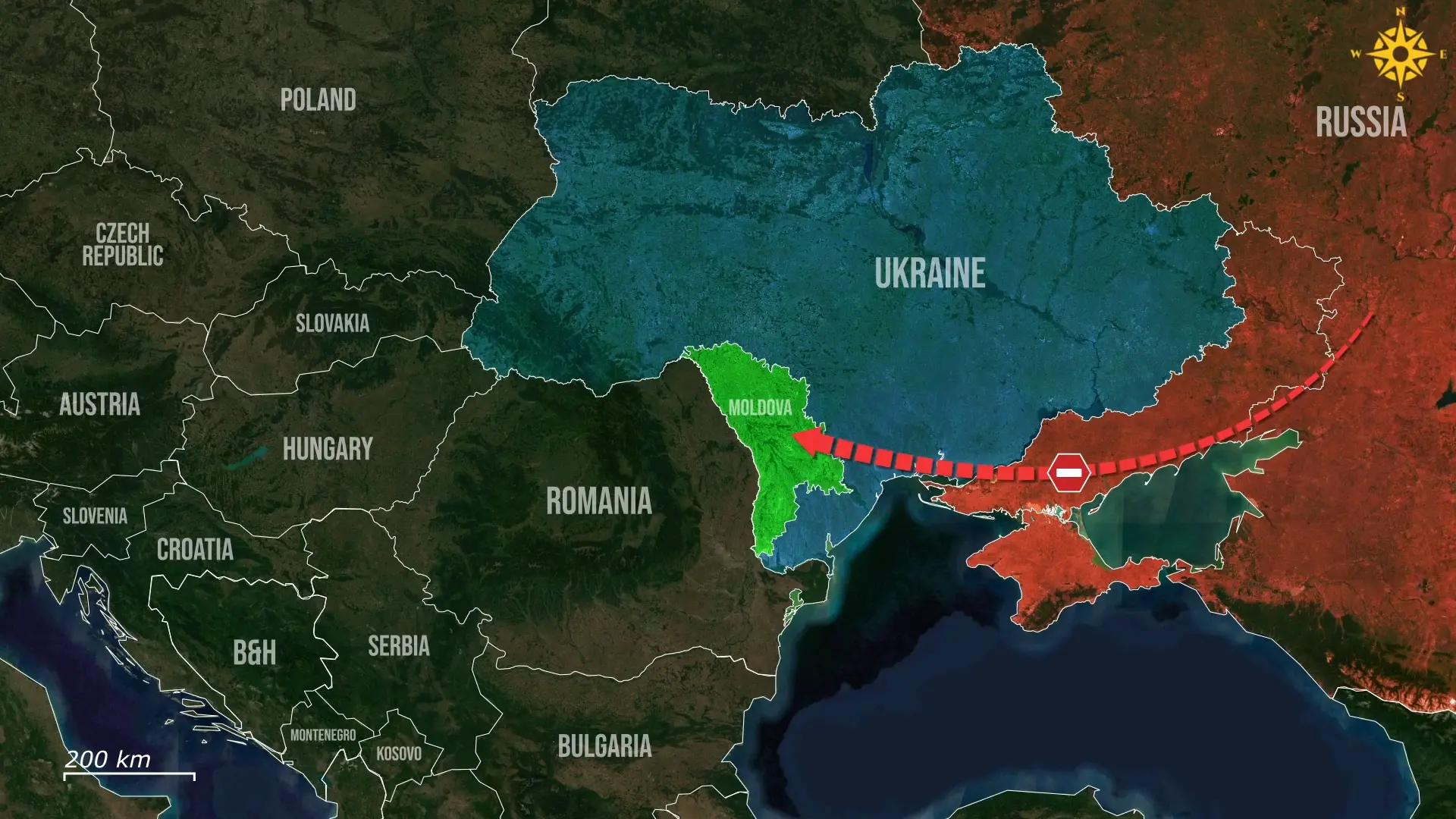

The Russian goal is to establish a long-term naval foothold on the Red Sea by formalizing and expanding the Flamingo military base in Port Sudan. The facility would serve as a logistics hub for naval assets, surveillance points over key sea lanes, and a launchpad for military and economic influence in Africa and the Middle East. Private military networks tied to Russia’s defense establishment, which evolved from Wagner, have used Sudan for training, logistics, and the evasion of sanctions.

With gold and fuel routed through Sudanese intermediaries, Russia’s presence in Port Sudan has allowed it to operate quietly but effectively, far from Western oversight.

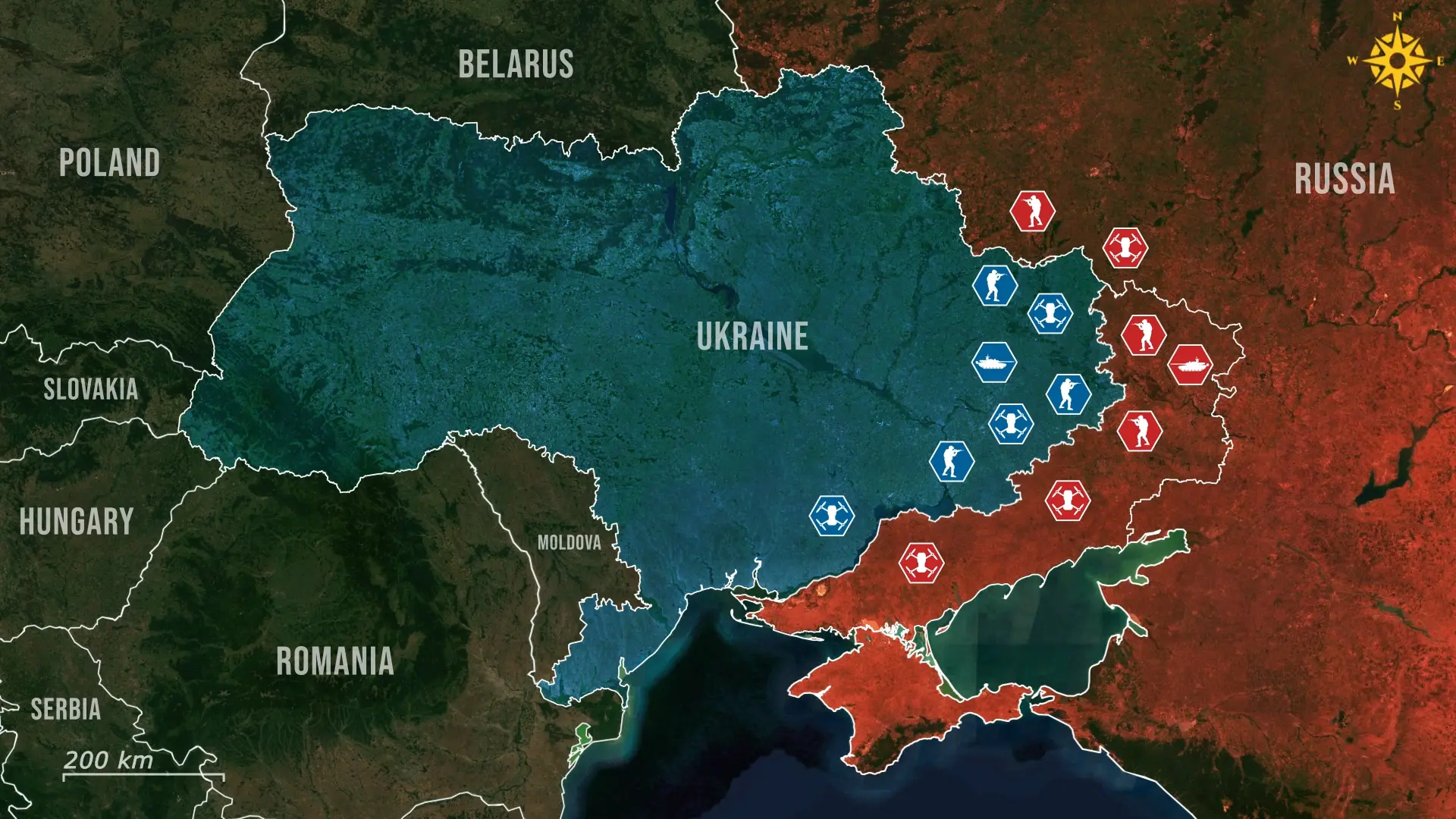

Sudan is now in the middle of a civil war between two rival factions. On one side are the Sudanese Armed Forces, led by General Abdel Fattah-al Burhan, which control the east of the country, including Port Sudan and the formal government apparatus. They are supported by Russia, Iran and North Korea, who provide military equipment, advisors, and strategic backing.

On the other side are the Rapid Support Forces, a rebel faction led by Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, which holds large portions of western Sudan and key smuggling routes. The Rapid Support Forces are backed only by the United Arab Emirates, providing drones, funding, and political support. This foreign involvement has transformed Sudan’s internal conflict into a regional battleground, where the control of ports, airfields, and foreign military facilities has become central to both sides’ strategies.

Though initially framed as a neutral logistics hub, the Russian Flamingo base evolved into a support node for government-aligned Sudanese Armed Forces. Russian private networks were increasingly tied to the Sudanese Armed Forces, offering training, surveillance support, and military aid routed through the port.

These activities strengthened the government side and, in effect, turned Flamingo into a military asset with operational relevance in the conflict, making it a valid target for the opposition forces to strike. The Rapid Support Forces launched a calculated strike to deny their rivals access to strategic advantage. The attack was carried out using a wave of suicide-drones followed by a manned aircraft strike. The drones were meant to saturate air defense, clearing a path for the primary strike.

By targeting Flamingo, they aimed to disrupt Russian-backed logistics, undermine the government’s supply lines, and signal their willingness to escalate against outside involvement.

Satellite images confirmed that multiple buildings at the Flamingo base were destroyed. Additional strikes hit nearby fuel depots, radar stations, and the Port Sudan airport, where a Russian Ilyushin transport aircraft was reportedly destroyed. Russian-linked sources also acknowledged several military casualties. These attacks marked the most direct challenge yet to Russia’s position in Sudan.

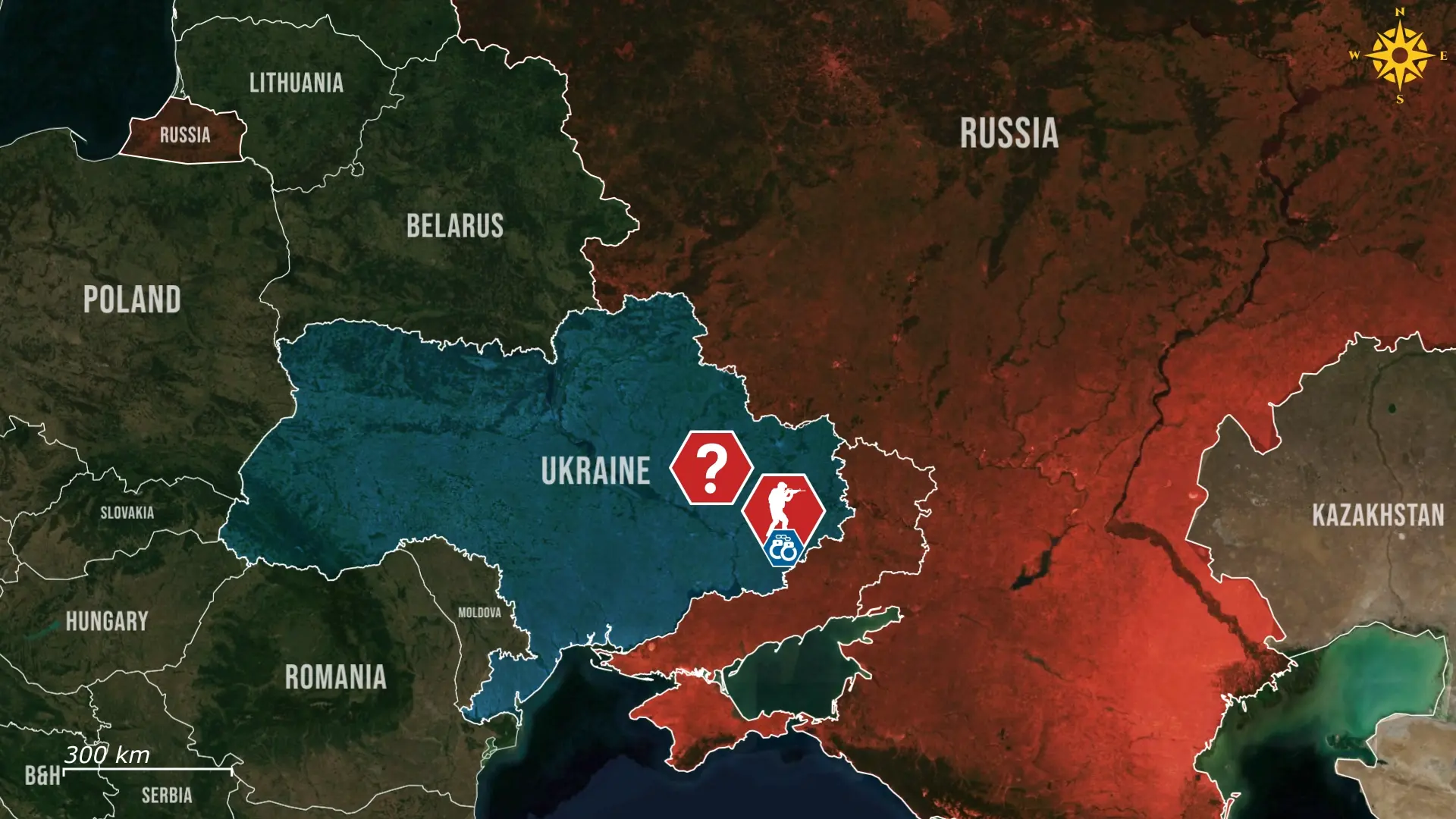

Until now, Russia operated under the radar, relying on deniable actors, local deals, and strategic ambiguity. But the strike exposed that model’s vulnerability. For the Sudanese Armed Forces, the attack validated concerns that accepting foreign basing rights or assistance also invites retaliation from rival powers. For the Rapid Support Forces, it showed that even highly protected foreign-backed installations could be hit if properly targeted.

In response to the strike, Russia is reinforcing the site through private military networks, increasing drone surveillance, and rerouting supply lines from Libya and Syria.

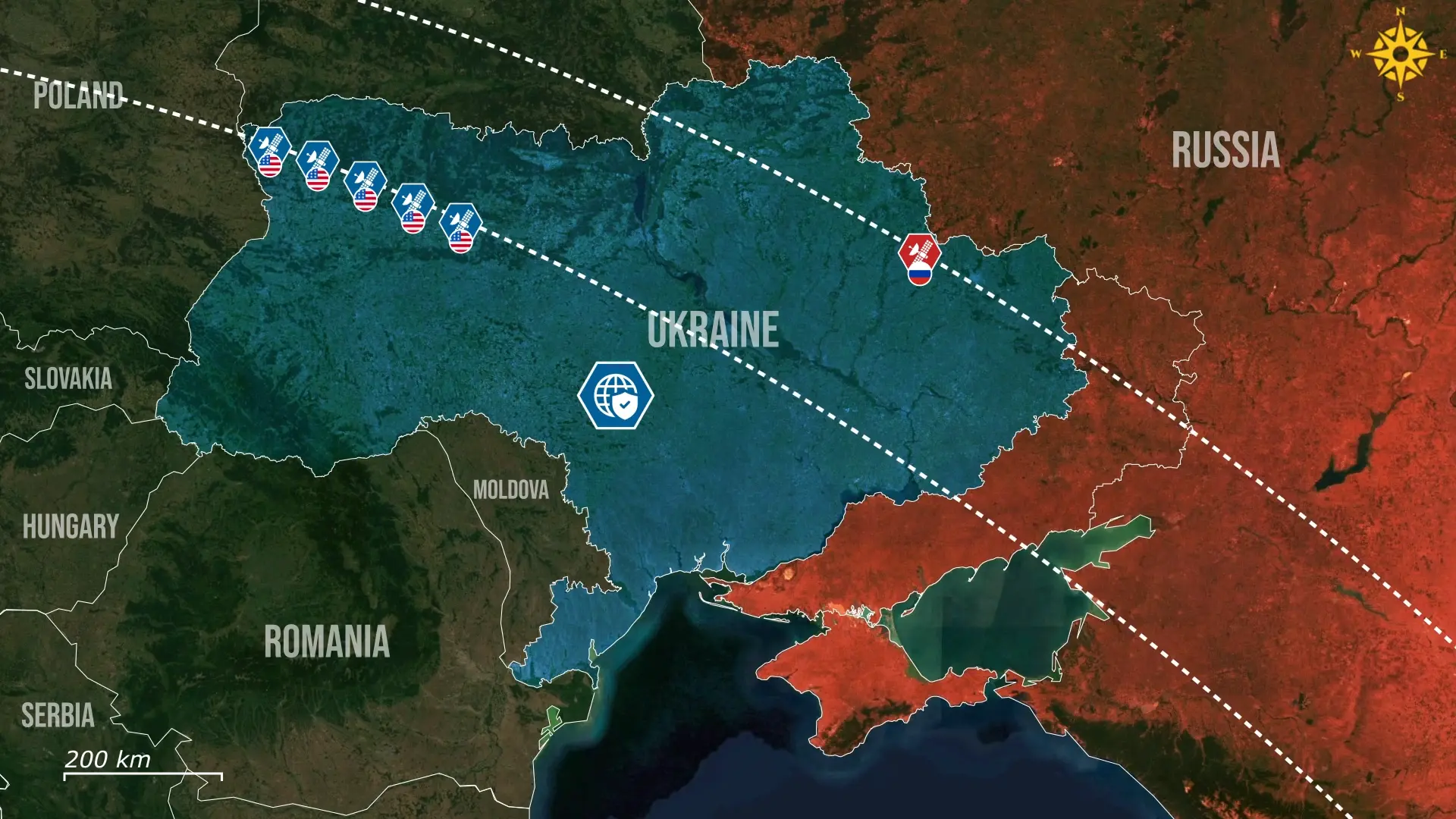

Quiet diplomatic outreach has begun towards Sudanese officials and Gulf mediators to limit further fallout. Meanwhile, the United States, taking the position of trying to end the conflict, is applying pressure on the United Arab Emirates to scale back drone transfers to the opposition’s Rapid Support Forces, and working with Egypt to shape a Red Sea security structure that excludes further Russian and Emirati military buildup.

Overall, the strike on Flamingo has forced Russia to defend a base it never officially acknowledged, yet one that holds major value for its influence across the Red Sea and northeastern Africa. The ability to quietly expand, using a gray network, deniable partners, and informal logistics, has reached its limit in Sudan. Whether Russia escalates, retreats, or absorbs further losses determines not only the future of Flamingo, but the credibility of its broader power projection strategy. Sudan, once an overlooked frontier, has now become a live test of how far Russia’s informal empire can extend.

.jpg)

Comments