Today, the biggest news comes from the Russian Federation.

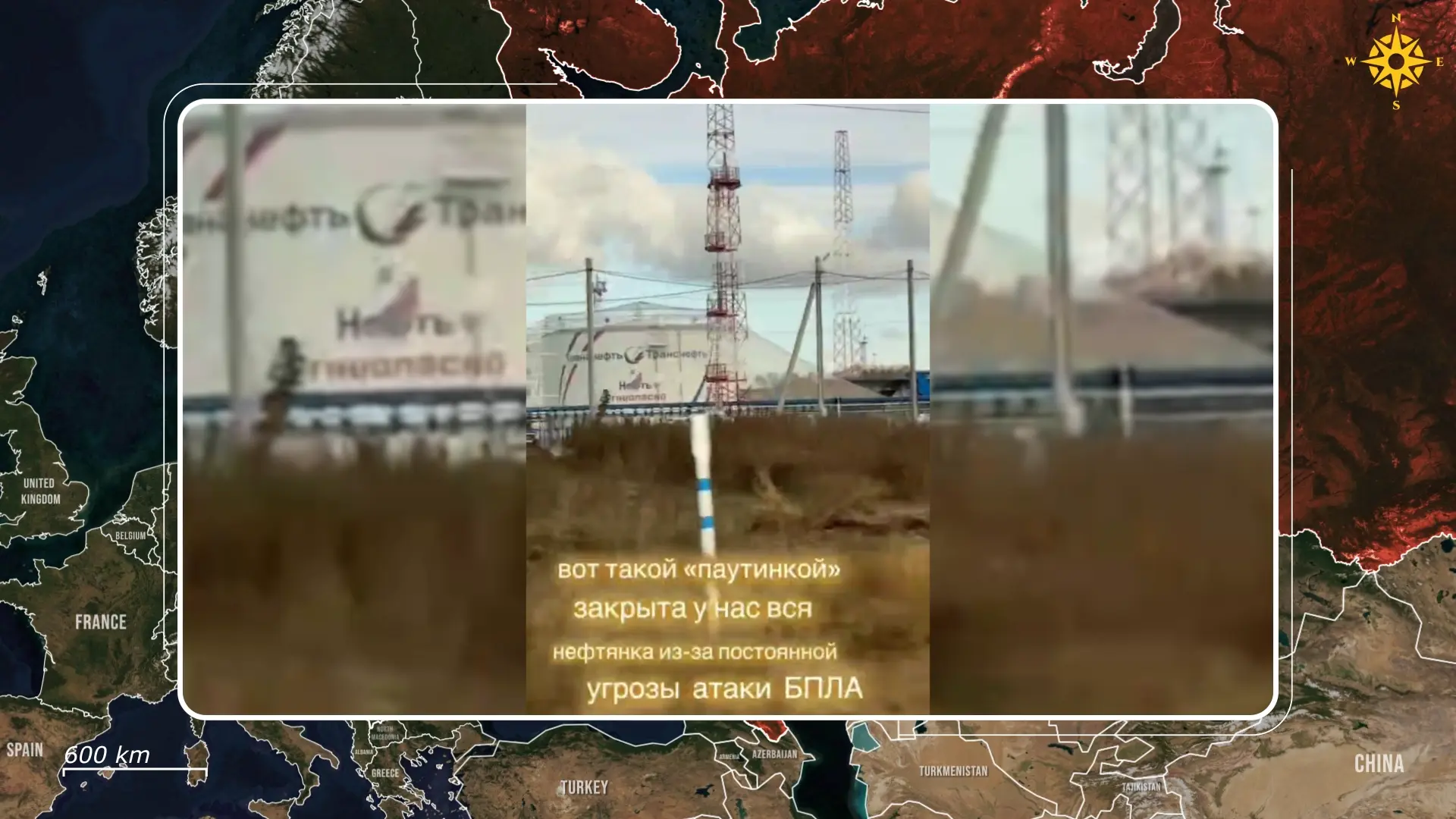

Here, Russians have started building metal and mesh cope cages around refineries to shield them from Ukrainian drone attacks, with calls to expand the structures and even build the cages around whole industrial cities. What began as a frontline improvisation has now spread deep into Russia’s industrial heartland, reflecting both the reach of Ukraine’s drone campaign and Moscow’s growing desperation to protect its fuel and industrial base.

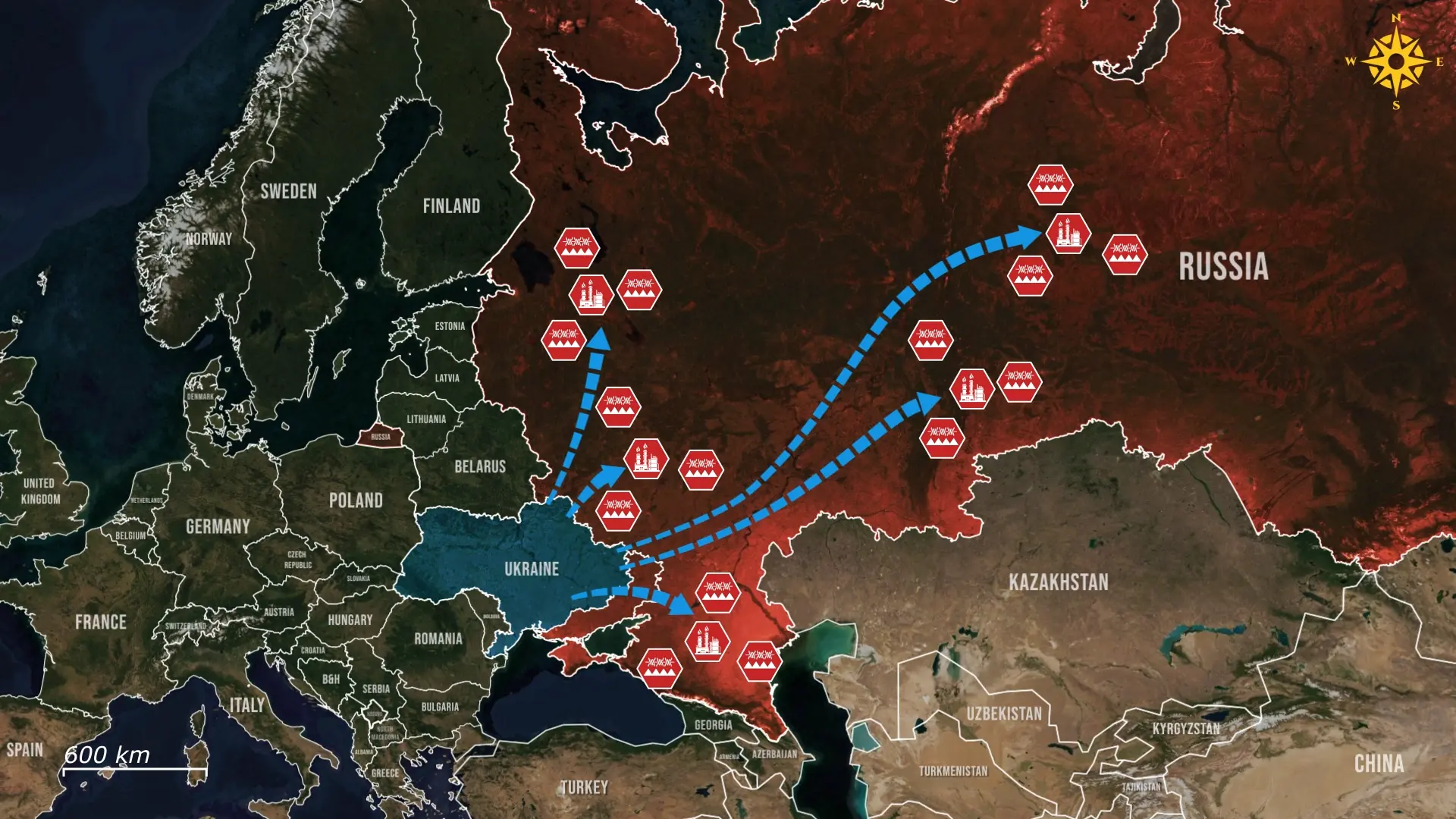

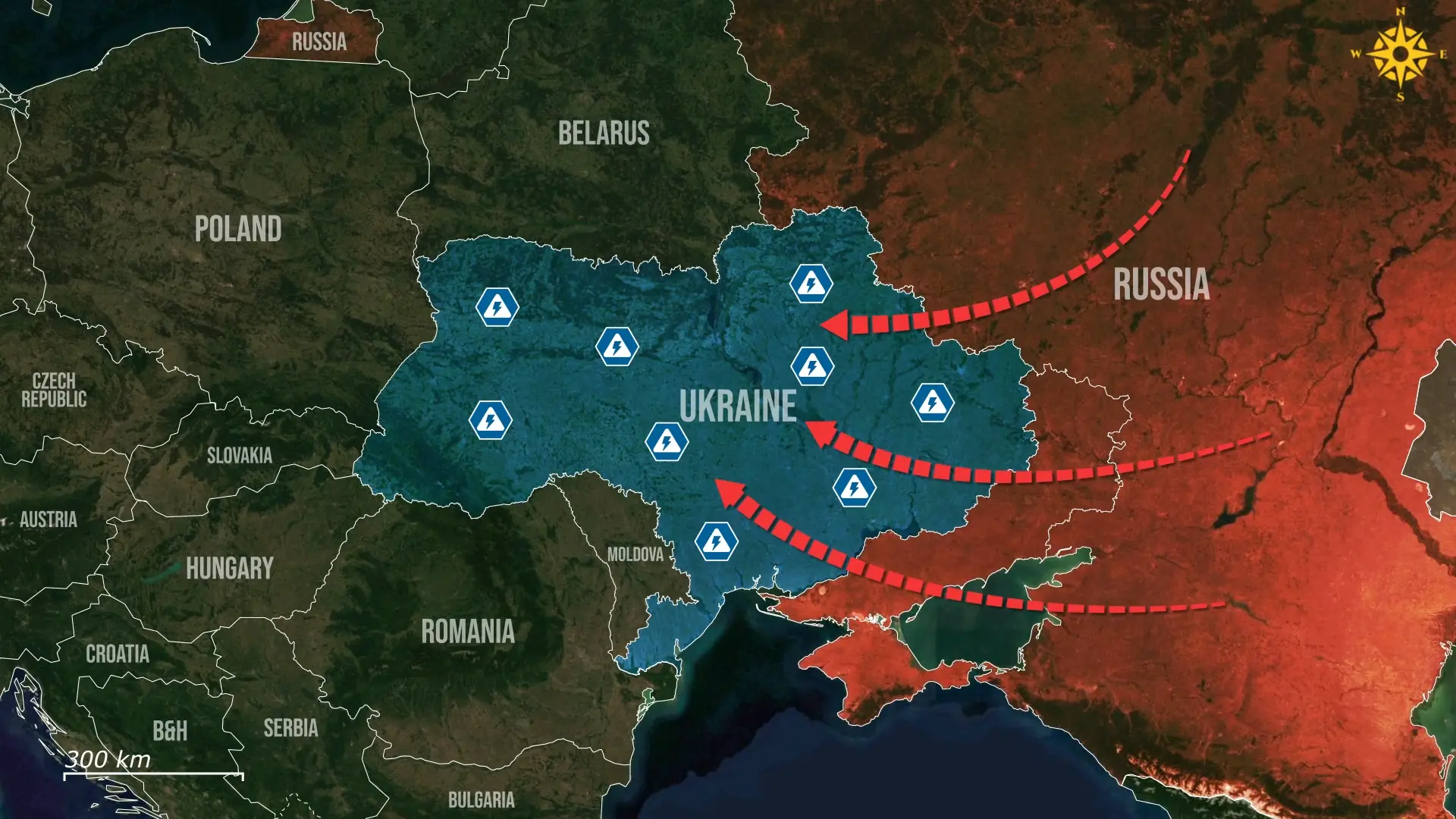

Ukraine’s strikes on Russian refineries have been among its most effective long-range operations of the year. In the past months, Ukrainian drones have hit at least nineteen refineries across Russia, knocking out an estimated fifteen to twenty percent of national refining capacity. The campaign has consisted of repeated strikes, with these refineries being the top targets to cause maximum damage, causing long term disruption of fuel exports and national shortages. Drone footage has additionally shown precision hits on fuel storage tanks in Ryazan, Tuapse, and Omsk, while thermal satellite imagery confirming several large-scale fires within hours of impact at each of the sites. One recent strike occurred at a fuel depot in Bologoye in the Tver region, where a drone struck an aviation-fuel tank but failed to ignite it, an outcome that may have contributed to the sudden rush to install cage protection.

With the damage mounting, Russian companies have turned to a makeshift defense borrowed directly from the battlefield. In Samara and other refinery hubs, metal frames and stretched nets cover storage tanks, pipelines, and loading platforms. These designs mimic the protective cope cages used on tanks at the front, a framework meant to detonate drones before they strike critical equipment.

Some facilities have even enclosed entire process units, forming little caged cities. The structures are appearing not just in Samar but also near Ufa, Oryol, and Novopolotsk, suggesting a coordinated effort backed by regional authorities rather than individual initiatives. The cages act as a blast diffuser, forcing an income drone to strike the metal mesh or frame before hitting the tank.

This can cause the warhead to explode prematurely and vent blasts upward, reducing the risk of full combustion. Early results suggest the barriers can absorb small impacts and deflect fragments away from exposed tanks, but their protection remains limited.

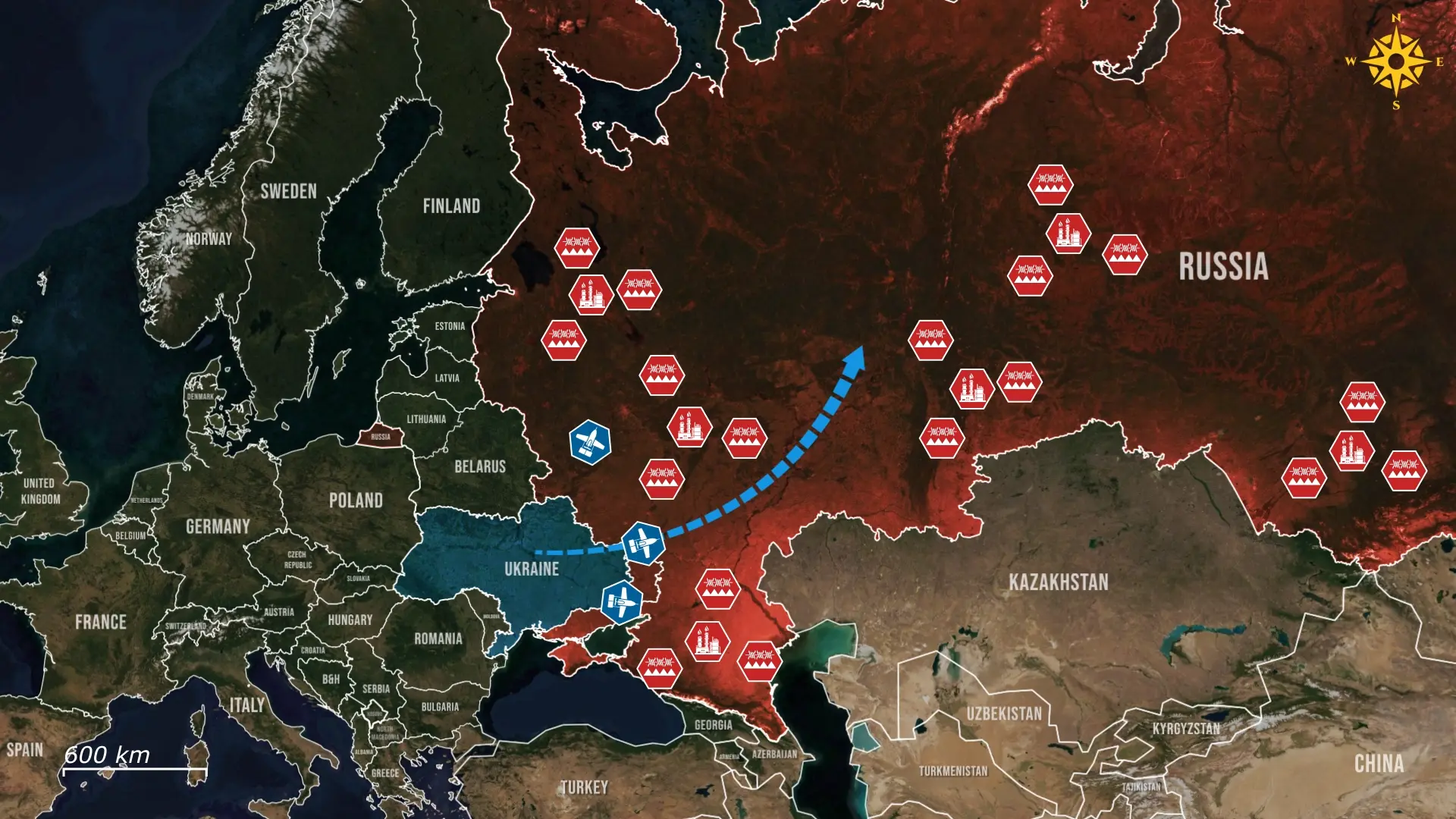

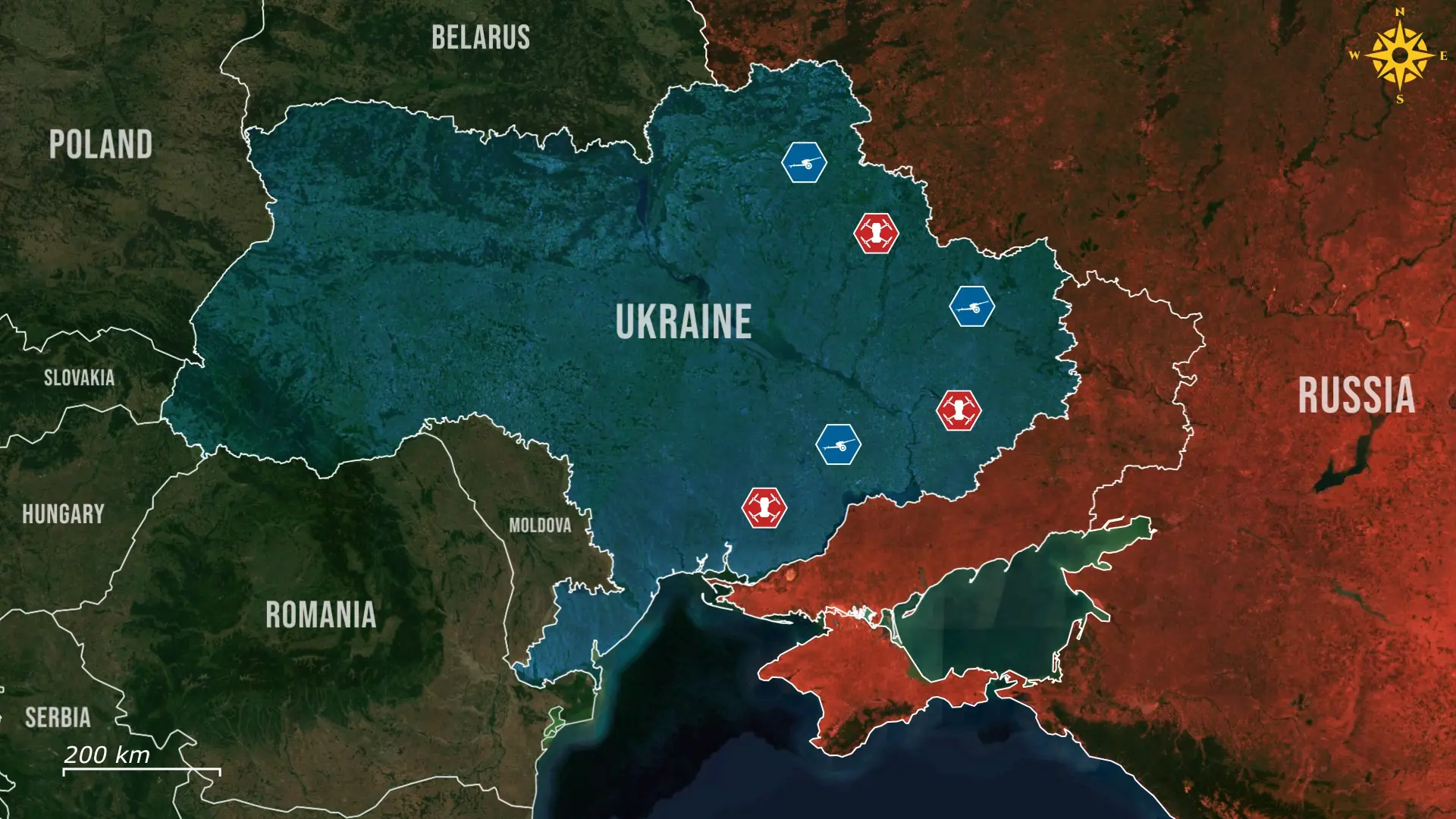

Many of the nets are thin, unanchored, and prone to tearing from heat and stock. Ukrainian drones have already been adapted with tandem warheads and downward-firing charges that can penetrate gaps in the mesh.

Others now target lateral pipelines, pump units, or rail-loading tracks, bypassing the overhead protection altogether. Even if a cage prevents a direct hit, a well-placed strike on connecting infrastructure can still disable an entire refinery section.

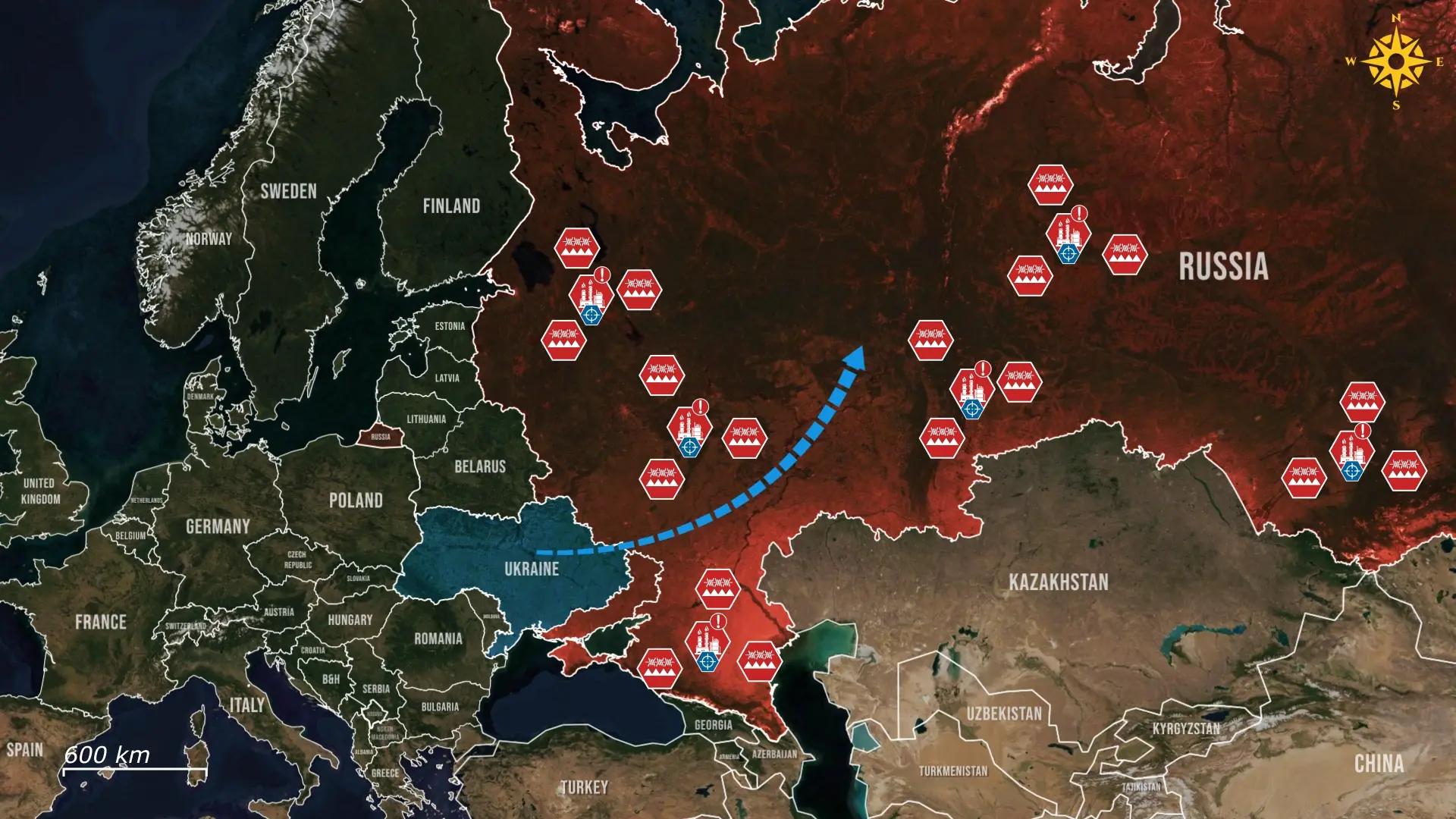

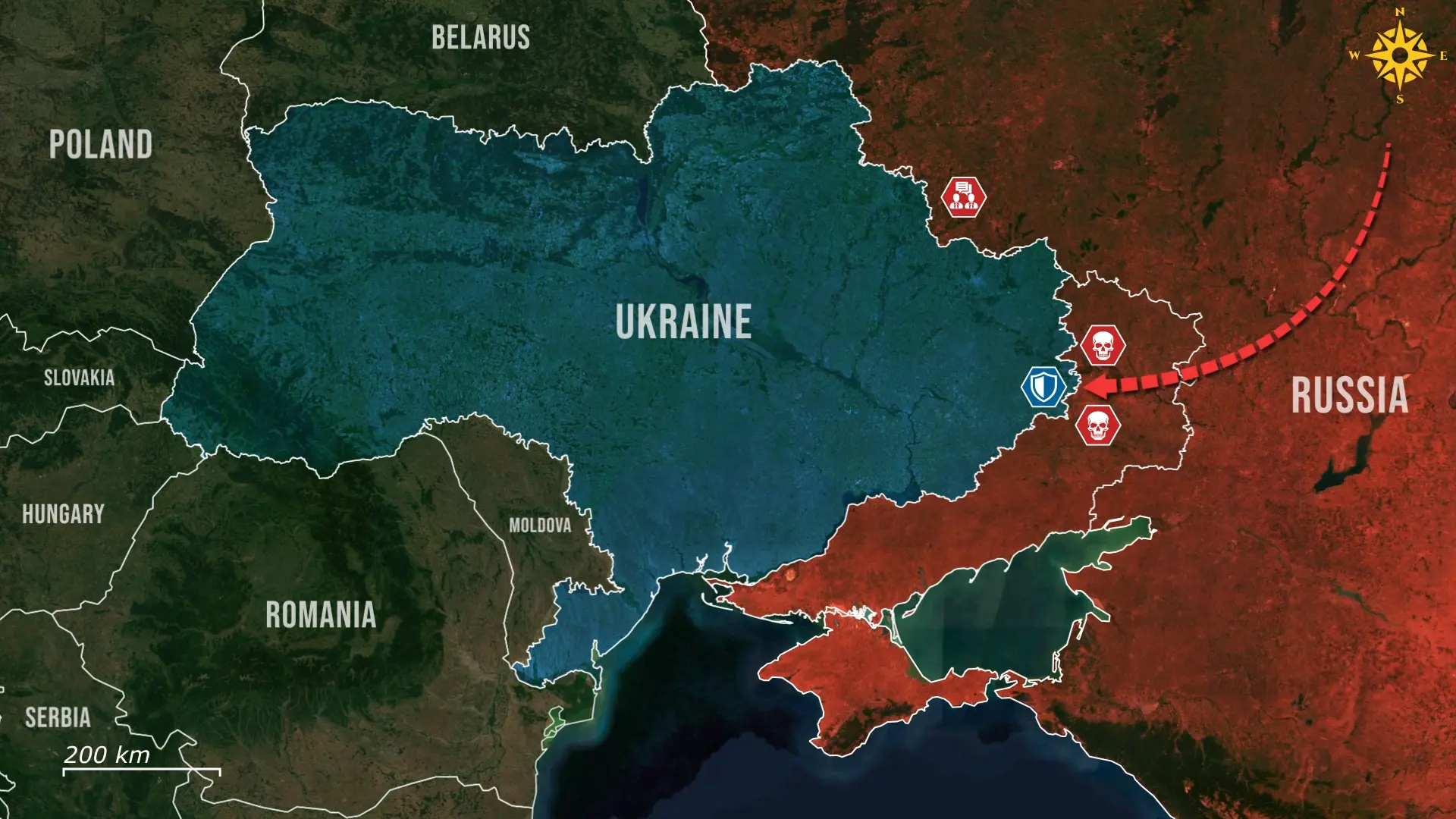

Inside Russia, these improvised defenses have stirred unease about who should be responsible for national security. The installation of cages is funded largely by the companies themselves, not by the state, and many within the energy sector quietly question why industrial sites must now shoulder the burden of air defense. Russian billionaires argue that the cost of building steel frameworks, maintaining watch teams, and installing sensors should come directly from taxes that already fund the security forces. Some officials defend the practice as pragmatic self-protection, but others see it as an admission that regular air defense has failed to keep pace with Ukraine’s expanding drone range. For many workers, the cages are as much psychological reassurance as they are physical protection.

Overall, the spread of these caged cities marks a revealing new stage in the drone war. It shows how Ukraine’s strikes have reached deep enough to reshape Russia’s industrial landscape and public morale, exposing the limits of the country’s failing air defense system. Yet the cages also highlight how defensive improvisation rarely keeps up with offensive innovation. If Ukraine continues to refine its tactics with heavier drones, simultaneous strikes, or a initial explosion to blow open the cage, Russia will face a costly cycle of damage and reconstruction.

What began as a short-term adaptation may become a long-term liability, drain resources while doing little to restore real security. In that sense, the new cage structures are less a sign of protection rather than a visible symbol of vulnerability, evidence that the war has now reached the core of Russia’s energy infrastructure.

.jpg)

Comments