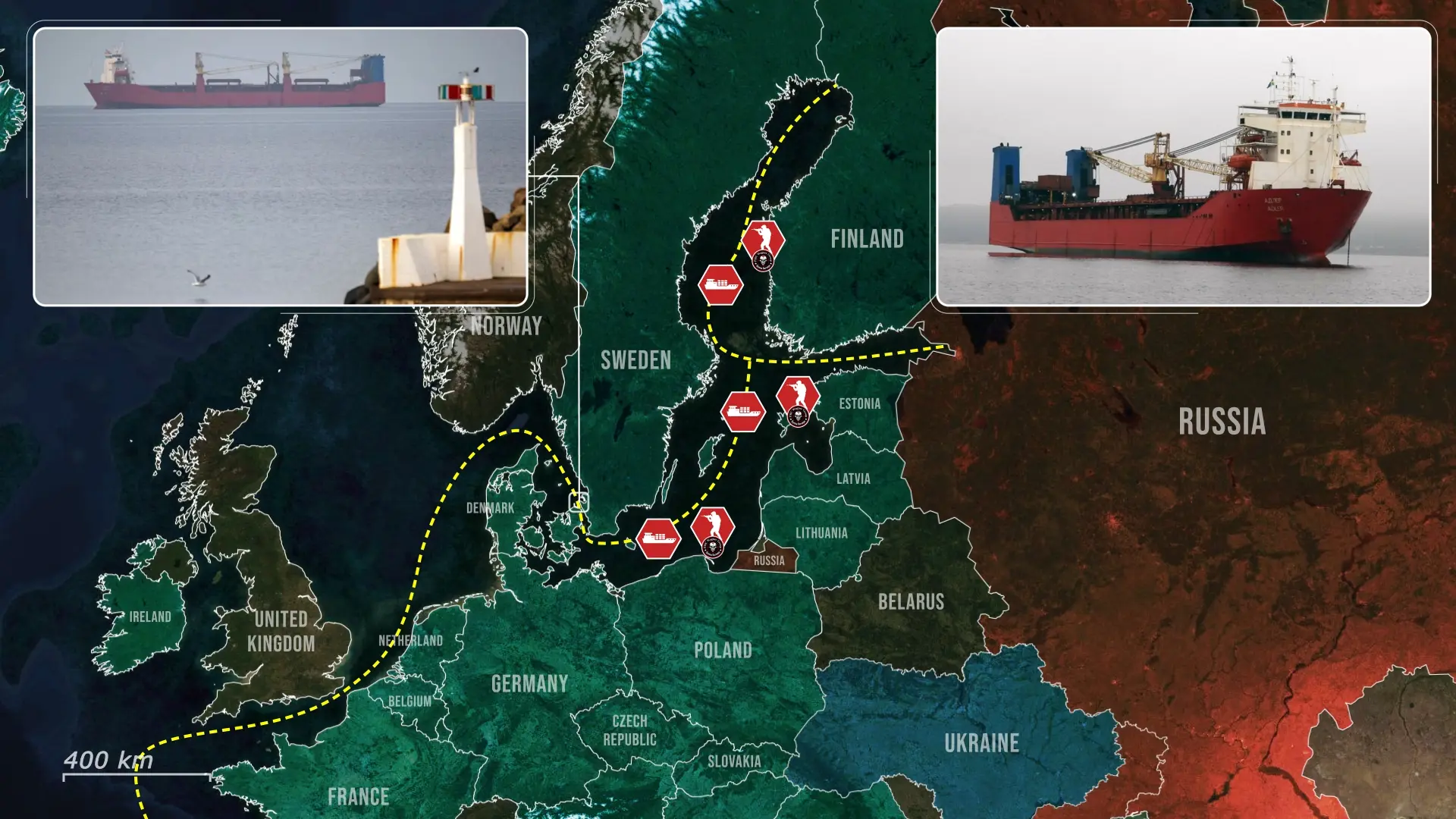

Today, the biggest news comes from the Baltic Sea.

Here, Russia’s shadow fleet is coming under mounting pressure in the Baltic, as interceptions increase and European states move more aggressively against sanctioned vessels. However, now Russia is responding by placing Wagner mercenaries on board these ships, bringing one of its most violent forces directly into Nato-monitored waters.

The European Union has just released a new sanctions package targeting forty-one additional shadow fleet vessels, bringing the total to more than six hundred ships now barred from European-linked ports, insurance, and services. These ships are losing access to harbors, maintenance, and technical certification, which forces Moscow to rely on improvised routes that squeeze through increasingly narrow corridors. Beyond oil, these vessels also move sensitive cargo linked to Russia’s war effort, which makes each interception far more consequential than a financial loss alone, and as enforcement tightens, the risk shifts from paperwork violations to direct seizure.

This shift became visible when Swedish authorities detained the Russian cargo vessel Adler after it entered Swedish waters with unresolved documentation issues. The ship’s owner is sanctioned for transporting materials linked to Russia’s weapons production, and when Adler suffered engine trouble in Swedish waters, the crew could not produce clean documentation. Swedish authorities boarded immediately, as the detention came amid growing reports that Russia has begun placing Wagner mercenaries on board shadow fleet vessels, raising the stakes for any inspection or boarding operation, and signaling that European states are no longer intimidated by the possibility of armed Russians on these vessels. If they boarded knowing Wagner might be present, it shows confidence, and if they boarded knowing Wagner was not there, it shows a level of intelligence penetration that Moscow cannot ignore.

This is the context in which Wagner has returned to the sea, as Russia is placing combat veterans with a record of severe violence on merchant ships to maintain board authority and deter foreign inspections. According to Danish maritime pilots, once Wagner personnel are on board, they often restrict access to the bridge and interfere with communication between captains and port authorities, and push for routing that avoids areas where inspections are common.

Wagner fighters were known in Bakhmut for killing deserters with hammers and other cruelty to Ukrainians and their own, and now they are deployed on ships where even minor disputes can escalate quickly, and for Moscow, Wagner functions as a last-line enforcement tool. Their role is to ensure that vessels keep moving even when legal and operational risks become unacceptable by normal commercial standards.

Crews bullied, beaten, or threatened by the mercenaries may even quietly signal nearby Nato ships for help, or attempt to sabotage equipment to force an emergency stop in Western waters, with the Adler’s crew possibly sabotaging the engine before they reached a Russian port, and Wagner’s would come on board. On top of that, owners of leased ships may object to hosting armed Russian soldiers, whose presence massively increases legal liability and operational danger. A single violent incident between Wagner and crew could bring Nato naval forces directly into contact with Russian mercenaries and shadow fleet operators in the middle of crowded shipping lanes.

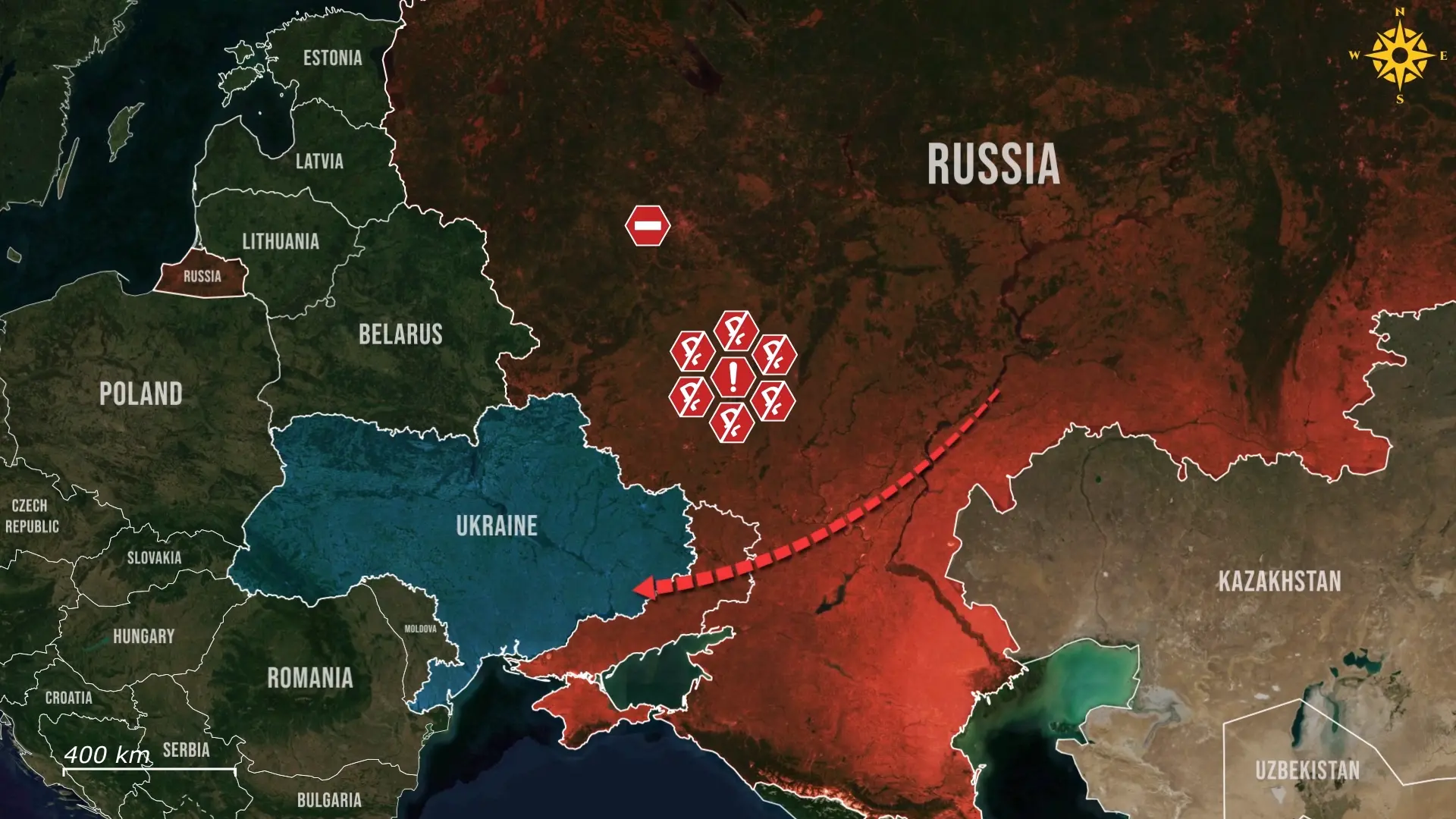

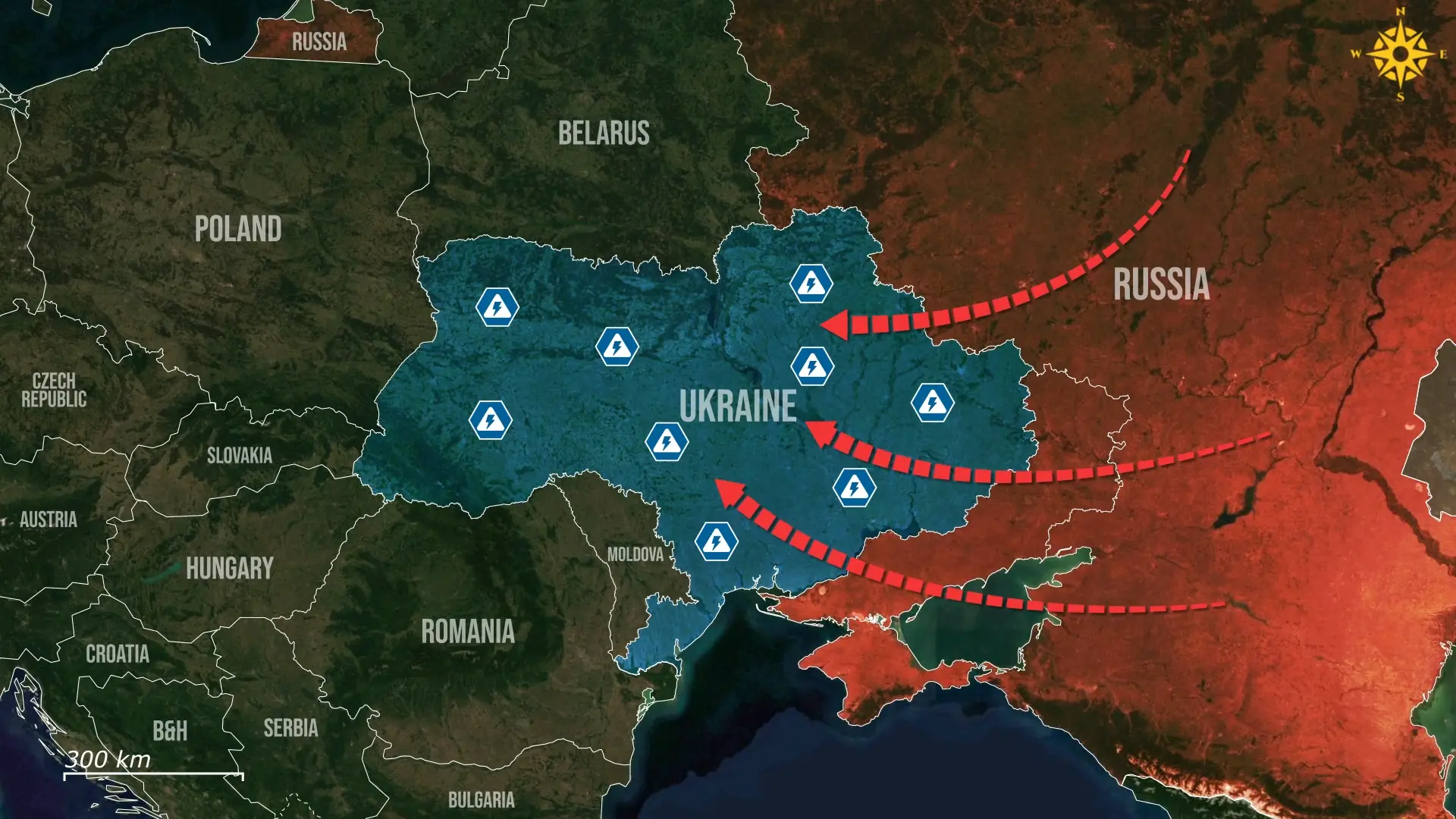

The case of Adler matters because it highlights how the shadow fleet is being used not only for oil, but for moving weapons and military-linked cargo. Western officials assess that a substantial portion of Russia’s imported ammunition components, explosives precursors, and sanctioned industrial equipment now arrives by sea, precisely because land routes and air transport are more exposed to interception. If vessels like Adler are increasingly detained or disrupted, Russia does not just lose revenue but risks bottlenecks in the supply chains that feed its weapons production.

Overall, Europe’s expanding sanctions and Sweden’s detention of Adler have pushed Russia into militarising its merchant fleet, creating an unstable environment in the Baltic. Wagner’s return to these waters increases the risk of conflict at sea, mutiny on board, and confrontations with Nato forces. This trajectory increases the risk of confrontation in the Baltic, where civilian shipping, armed mercenaries, and Nato forces are now operating in proximity, leaving Russia with limited room to de-escalate.

.jpg)

Comments