Recently, Russia’s main airbase in Syria has come under threat in a way not expected before. What could normally be dismissed as a local security incident has instead exposed the fragility of Russia’s military footprint and raised deeper questions about its future role in post-Assad Syria.

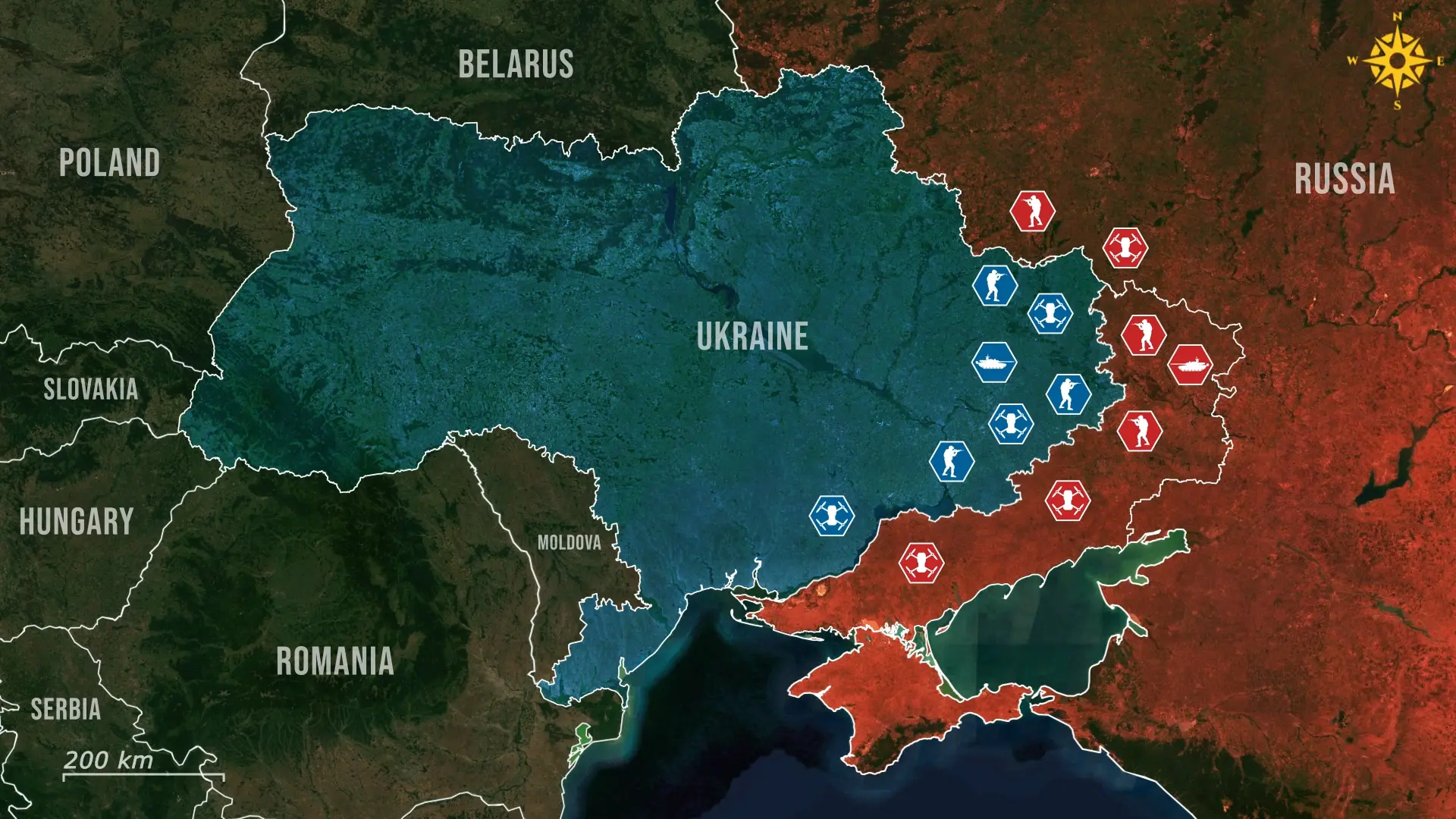

Recently, the Russian Khmeimim air base in western Syria was attacked when several militants climbed over the perimeter fence and launched a close-quarters assault on one of the outer guard posts. Armed with grenades and small arms, they engaged Russian personnel in a brief but deadly firefight. Two Russian soldiers were killed, and multiple others were wounded, before the attackers were neutralized. The bodies of the attackers were later claimed by local factions loosely tied to Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, a paramilitary group located in Syria, otherwise known as HTS. However, the group denied any responsibility for the attack. Still, the level of coordination, paired with sniper rifles and grenades, suggests this was not a rogue act.

Russian electronic warfare systems were deployed, and several aircraft were launched to resecure the perimeter.

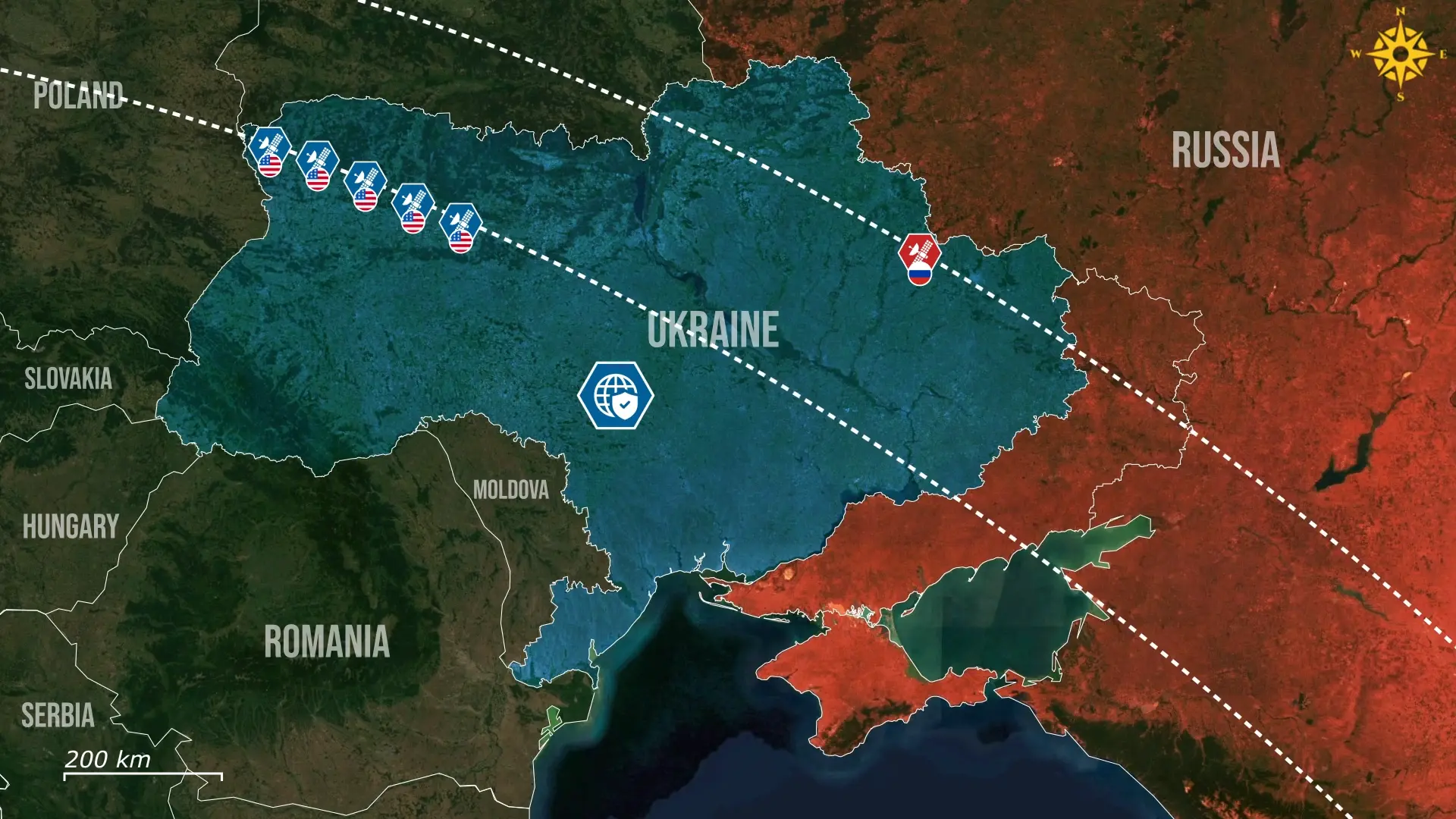

The Khmeimim Air Base is one of Russia’s most strategic military assets outside its borders. Located near the port of Tartus, it allows Russia to control vital Mediterranean airspace, resupply Russian-aligned units, and maintain power projection across the Middle East. Alongside its naval presence in Tartus, Khmeimim functions as a key staging ground for Russian operations across Syria and North Africa.

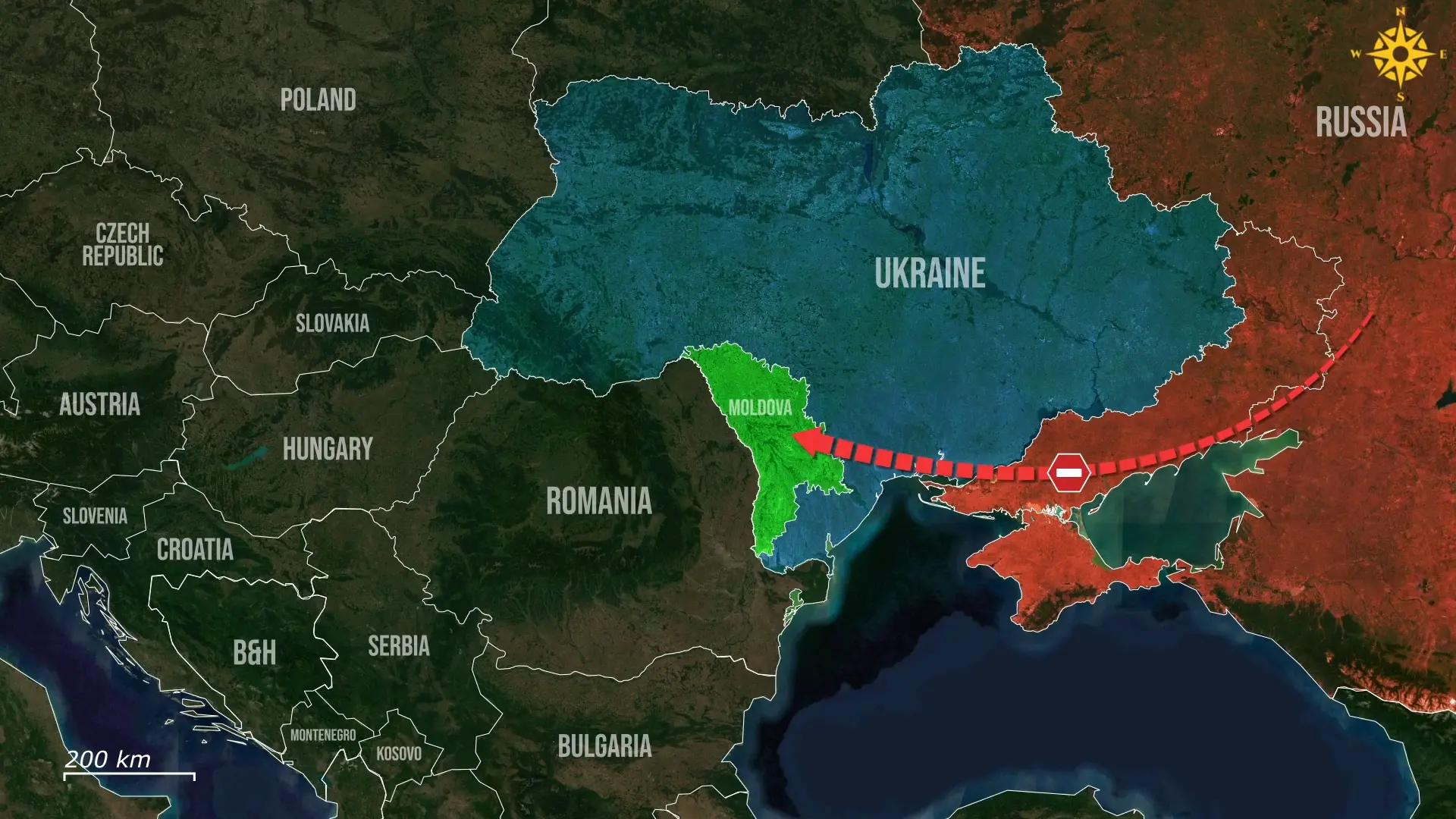

The goal for Russia is to preserve access to these military facilities in a post-Assad Syria. Losing the bases would mark a major setback in Moscow’s regional presence and weaken its influence in key theaters like the Red Sea and Eastern Mediterranean. However, talks between Russia and Syria over the future of Khmeimim and Tartus have reached a stalemate. After Assad fled to Russia, Syria’s interim president, Ahmed al-Sharaa, who led the coalition that ousted Assad, demanded his extradition in exchange for allowing Russian forces to maintain their bases.

Russia refused, and since then, negotiations have frozen. Ahmed al-Sharaa publicly states that he is open to allowing Russia to retain its presence, but only if it serves Syria’s interests. However, Moscow’s refusal to extradite Assad has been viewed as a red line. In response, Russian officers at Khmeimim have restricted Syrian civilians' access even to the surrounding checkpoints and supply zones, raising tensions with local authorities.

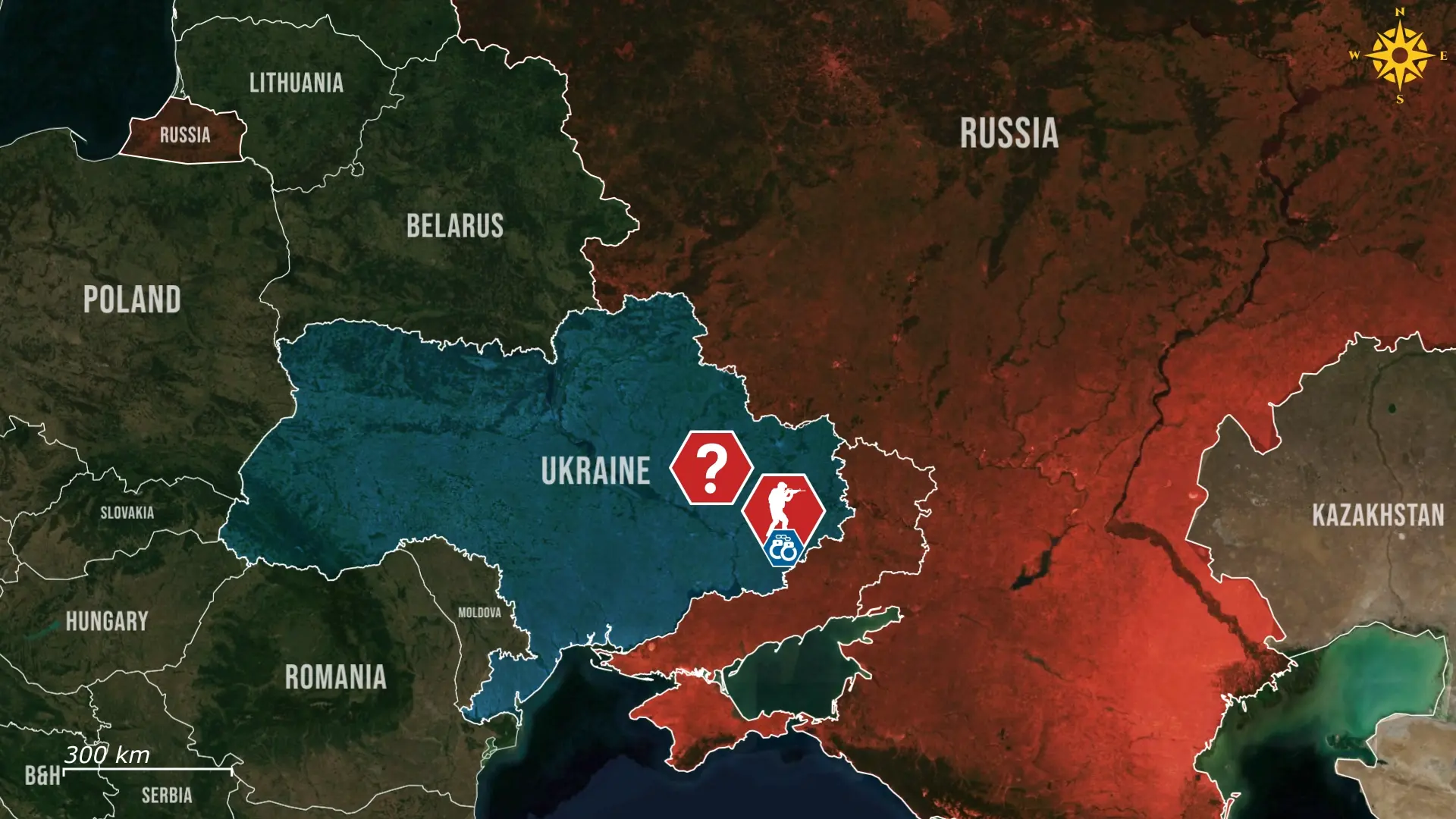

Internally, the new Syrian government faces its challenges. Ahmed al-Shaara has ordered all armed groups to disband or integrate into the newly formed Syrian army. He aims to centralize military and political control, hoping to prevent another fractured post-war state. However, resistance remains. Many groups, especially those previously linked to Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham or foreign fighters, have ignored the mandate. The attackers at Khmeimim are believed to come from one of those unaffiliated groups. It remains unclear if al-Sharaa ordered, tolerated, or simply failed to prevent the attack.

What is clear is that the broken nature of militant groups, some of which are still armed and autonomous, poses a serious risk to the new Syrian government. Allowing Russia to remain indefinitely could result in Moscow destabilizing the country from within or supporting breakaway regions if its influence is denied.

Analysts say Russia may try to keep its influence by holding onto military zones directly or backing friendly militia in key areas. Reports suggest that Russia is now positioning itself to back future Alawite separatist ambitions in the coastal regions, where many Alawites, historically loyal to Assad, still hold influence. Russia is quietly building ties, offering old pro-Assad groups shelter and protection against retribution from the new Syrian government. The new government opposes a long-term Russian presence if it is not beneficial to the country, and Moscow may escalate its involvement to protect its assets, making incidents like the attack on Khmeimim air base potentially politically explosive.

Overall, the attack on Khmeimim is not just a localized security breach; it is a possible harbinger of something much larger. Russia’s use of informal military networks and vague deals with local actors has made its position in Syria unstable and harder to defend. The new Syrian leadership is trying to reassert control but must now weigh whether Russia is a stabilizing partner or a long-term threat. The future of Russia’s military footprint in Syria will be defined not just by diplomacy but by exerting pressure in any form they can.

.jpg)

Comments