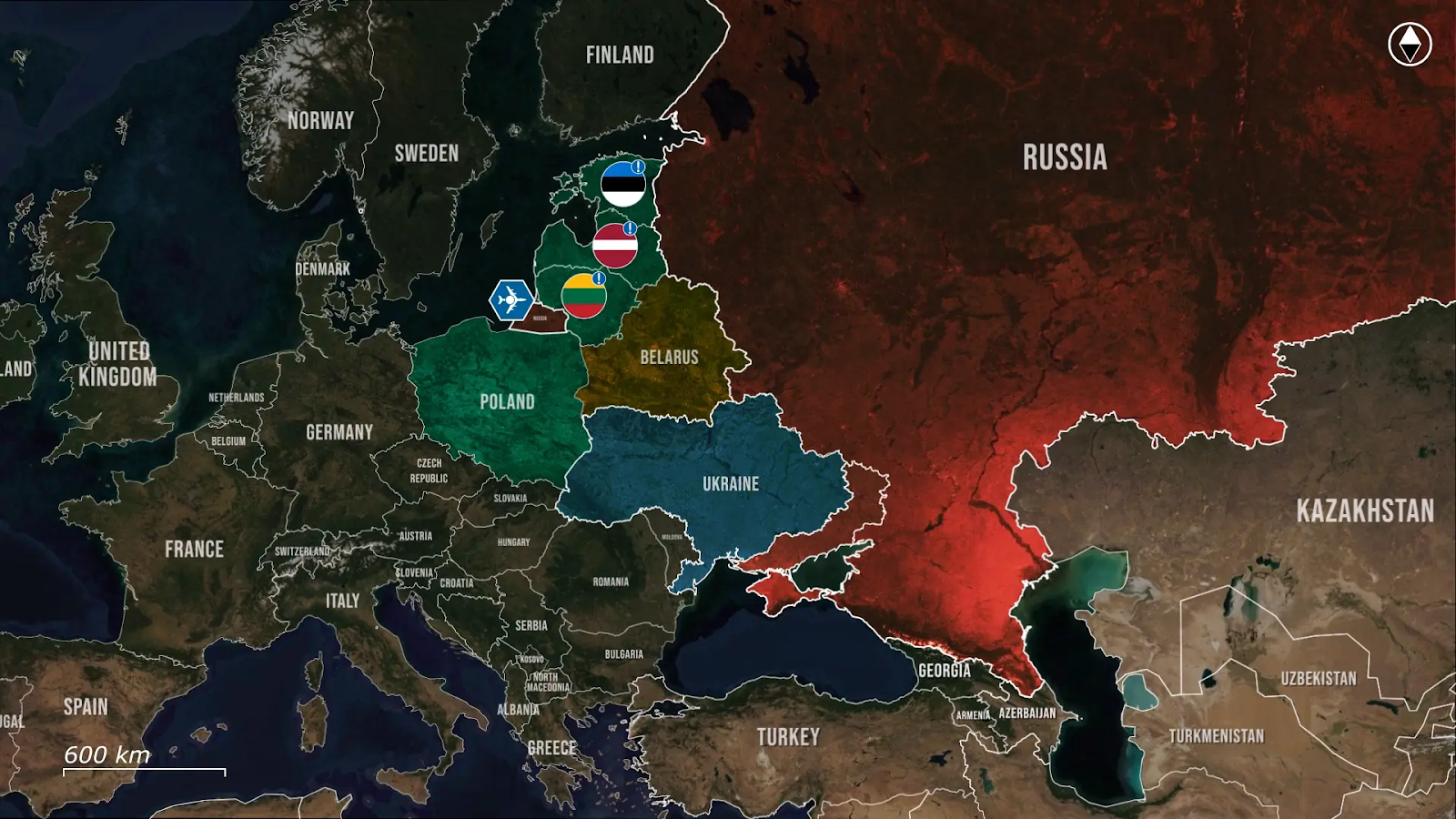

Today, the biggest news comes from the Baltic region.

Here, Nato surveillance flights over Kaliningrad and live-fire drills in Estonia suggest that Europe is no longer treating the Russian exclave as a passive threat. Instead, Kaliningrad is being studied and tracked, while its neighbors are quietly preparing for a worst-case scenario.

Recently, Germany’s military counterintelligence service has reported that Russian espionage cases nearly doubled over the past year. Officials say Moscow’s operatives are using more aggressive cover strategies and entering Europe via third countries like Serbia and Turkey to evade detection.

At the same time, cyberattacks and political interference campaigns have surged across the Baltic states. In just the last month, Lithuania reported GPS spoofing on its commercial aircraft, Estonia flagged coordinated hacks on state infrastructure, and Russian-linked groups funded several political rallies in Latvia. These are not isolated provocations; they mirror the early warning signs that preceded Russia’s invasions of Georgia in 2008 and Ukraine in both 2014 and 2022. The pattern is familiar, and its central node is Kaliningrad. Nearly every signal-jamming incident, radar incursion, or drone probe in the region traces back to the Russian exclave, making it the catalyst for any new escalation.

That threat is not new, but its urgency is. Kaliningrad is a heavily militarized Russian enclave wedged between Poland and Lithuania, and has long served as a launchpad for threats against nato. Home to Baltic Fleet warships, Iskander missile systems, and advanced air defense, it gives Moscow a constant forward presence inside EU territory. During previous standoffs, Russia used Kaliningrad to simulate nuclear strikes, stage snap exercises, and threaten shipping routes in the Baltic Sea. But in recent months, it has also become a nerve center for hybrid operations, coordinating cyber-attacks, transmitting jamming signals, and testing nato’s airspace readiness with frequent higher flyovers. In short, Kaliningrad is no longer just a base; it is a battlefield node already in use.

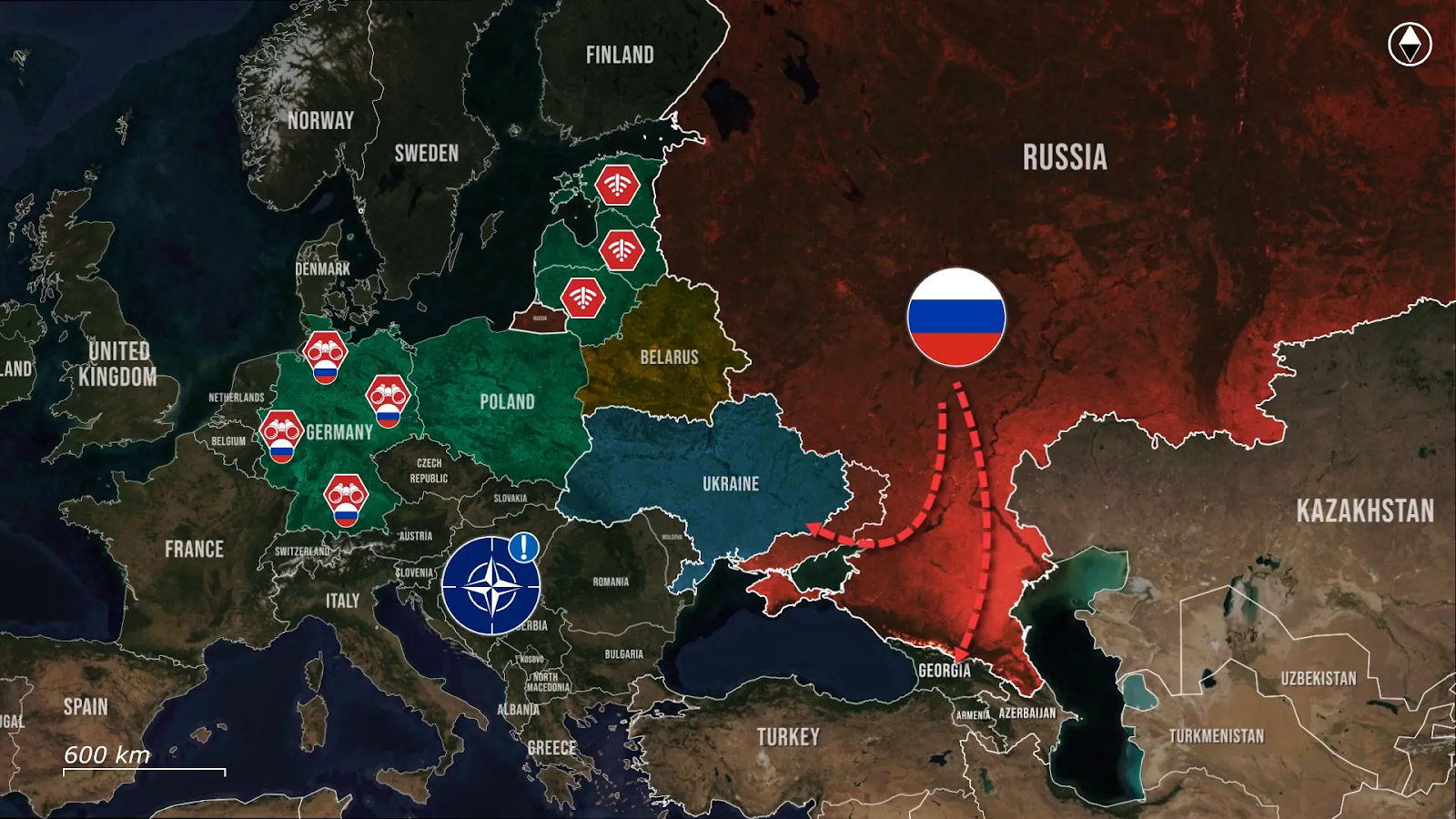

Now Europe is pushing back. Nato awacs surveillance aircraft have begun continuous flights over Poland and the Baltic Sea to monitor Kaliningrad’s military activity. Meanwhile, Estonia has just held its first-ever live fire drills using US-supplied himars, part of a six-unit acquisition aimed at boosting long-range strike capabilities.

The exercises focused on targeting simulated hardened positions, such as fortified bunkers and missile launch pads, the exact type of assets concentrated in Kaliningrad. Poland, which has received dozens of himars systems from the US, is preparing similar capabilities.

For frontline nato members facing the brunt of Russian pressure, these drills serve a clear dual purpose: readiness for counterforce missions and visible deterrence against Kaliningrad’s offensive potential. While no official scenario has been disclosed, these drills are being interpreted by analysts as a dry run for serious interdiction missions aimed at Russia: detecting, targeting, and disabling missile launch platforms inside the enclave.

In parallel, Poland has expanded troop deployments near the border, and Lithuania is accelerating work on reinforced border barriers.

If nato were to actually confront Kaliningrad militarily, the opening move would likely be a coordinated cyber and electronic warfare push, aimed at blinding Russian communications and radar coverage. This would be followed by continuous aerial reconnaissance through awacs and high-altitude drones to confirm positions.

Long-range precision strikes would then target key installations: Iskander launchers, air defense nodes and Baltic Fleet command centers. Himars batteries in Estonia and Poland could disable fixed missile sites, while German and US aircraft execute follow-on suppression missions. Naval forces would blockade Kaliningrad’s key port at Baltiysk to prevent reinforcement. Meanwhile, Nato ground units, already repositioned near the Suwalki Gap, would be tasked with containing any attempted Russian breakout into Poland or Lithuania. This is a hypothetical scenario, but it is now being actively rehearsed, with each exercise aligning more closely to an actual operational sequence.

Overall, the Kaliningrad threat that Russia spent two decades cultivating may be turning against it. Europe is no longer threatening the enclave as a static deterrent but as a live vulnerability that can be tracked, targeted, and potentially neutralized. For the Kremlin, this shift carries enormous risks: losing Kaliningrad would not only be a massive strategic blow but also a symbolic collapse of Russia’s forward posture in Europe. And for nato the message is clear: the era of passive containment is over.

.jpg)

Comments