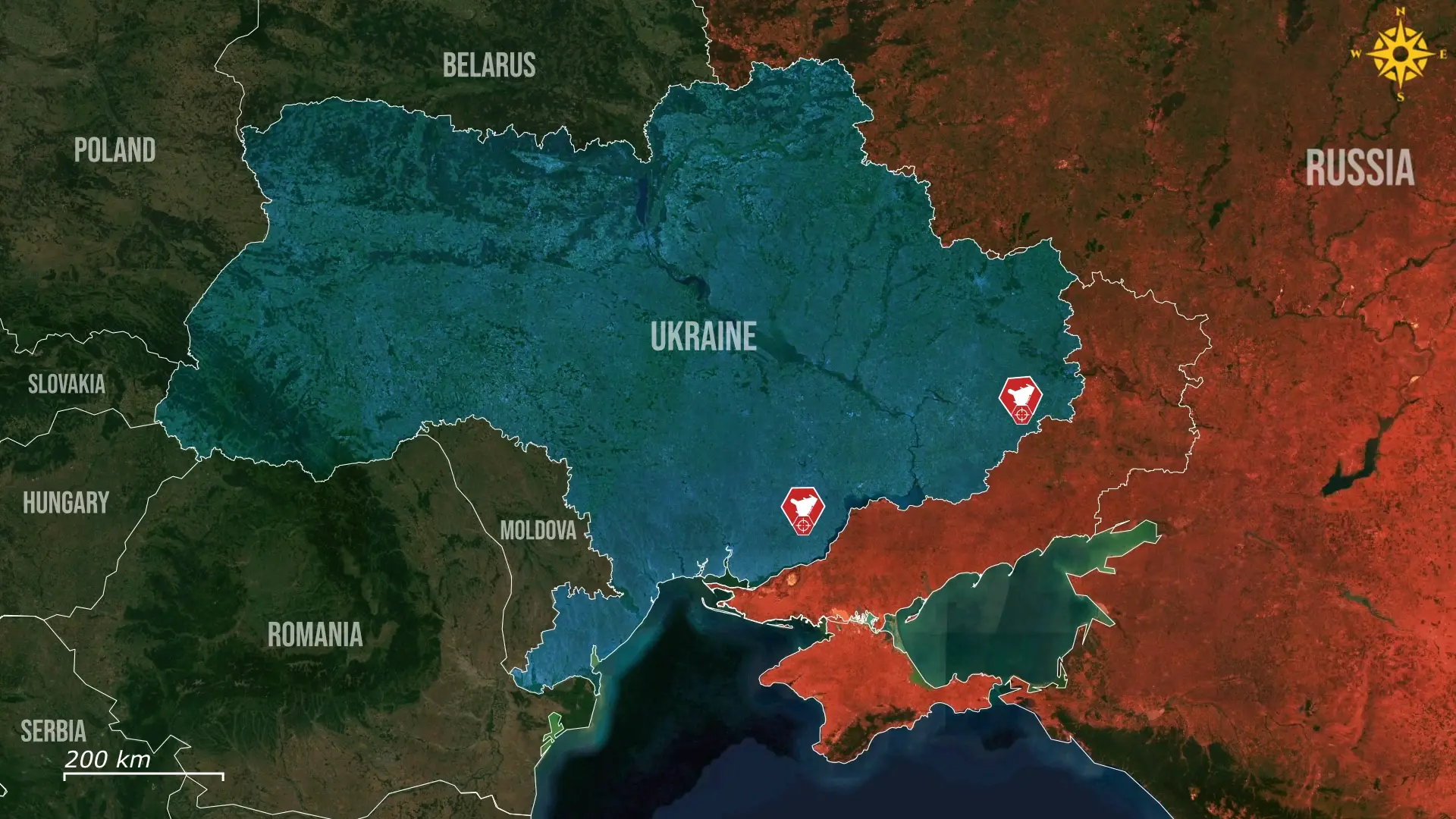

Today, the biggest news comes from the Black Sea.

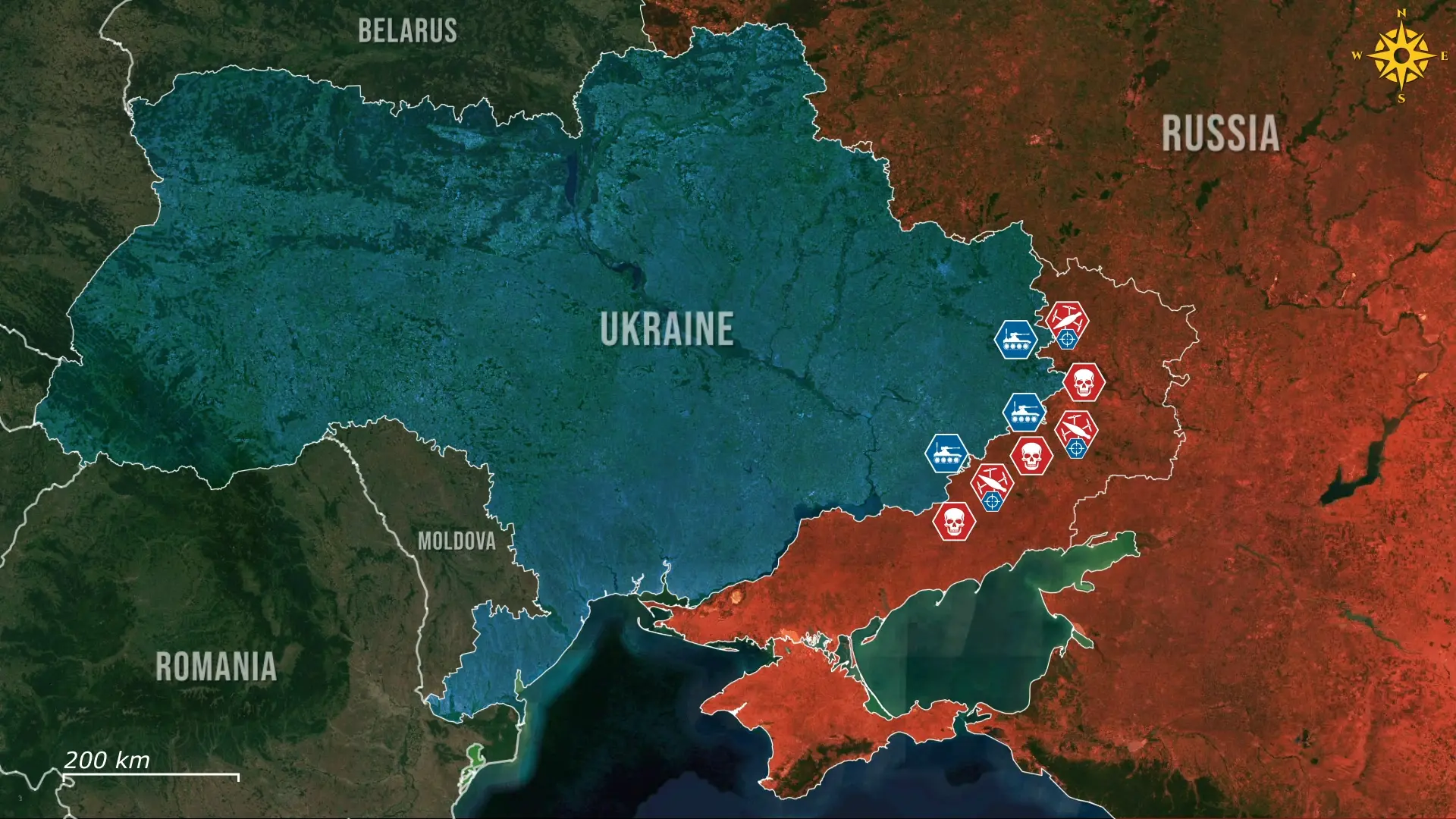

Ukraine’s strategy of targeting Russia’s shadow-fleet logistics has already resulted in 3 naval vessels taken out of commission in rapid succession, raising the risks of operating anywhere near Russian export routes. The results of this strategy turned out to be much more immediate and devastating than expected, with companies already pulling out their ships from the Russian shadow fleet and reassessing whether they can remain in the Black Sea and continue enabling the illicit Russian oil trade at all.

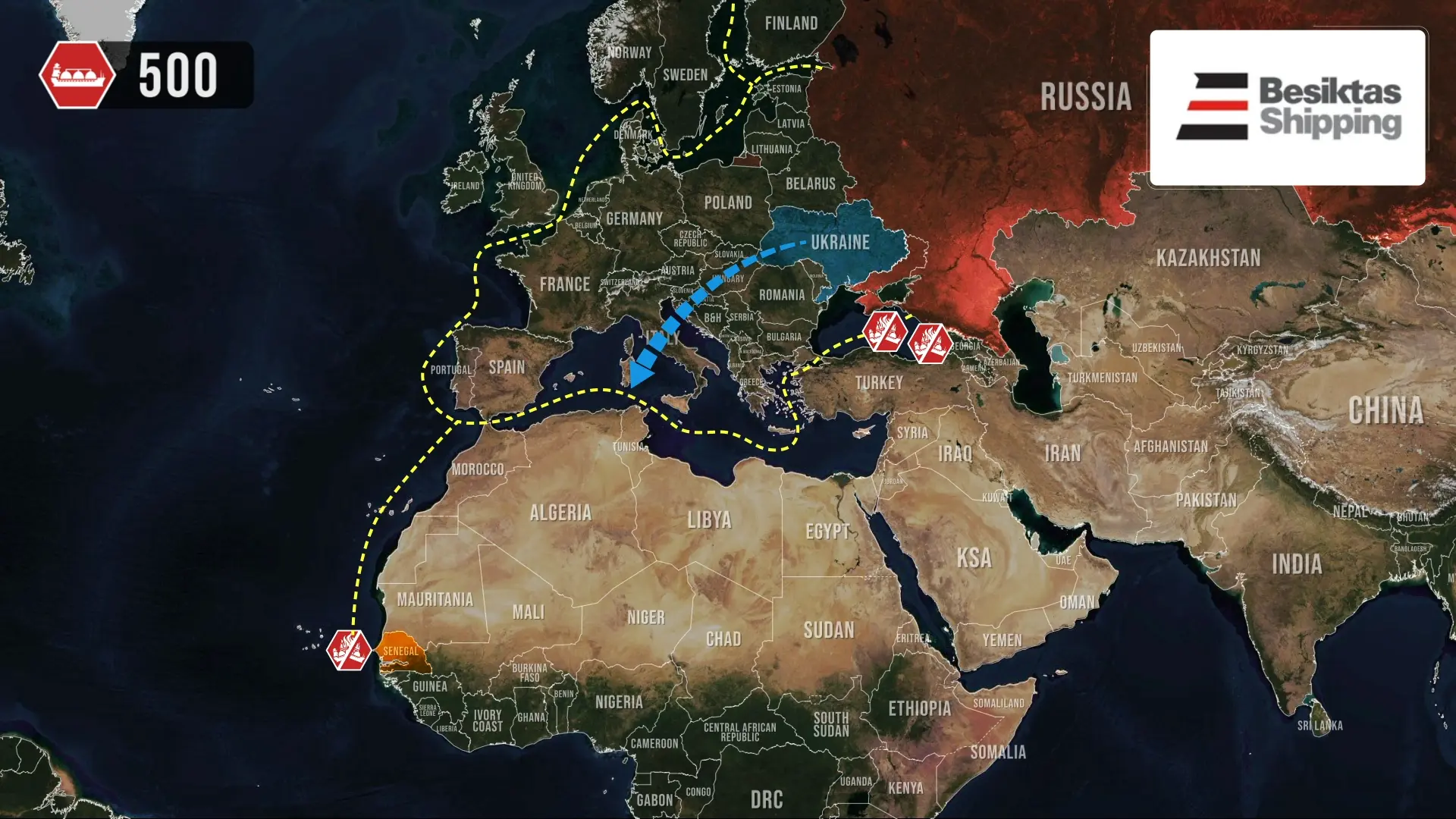

The loudest signal came from Besiktas Shipping, which stopped all cooperation with Russia after one of its tankers was damaged near Senegal. The company emphasized that it had operated within formal sanctions rules, even though its vessels still ended up serving routes connected to Russia’s shadow-fleet logistics. Besiktas controls around fifteen oil and chemical tankers, removing several hundred thousand tons of annual carrying capacity from Russia’s rotation the moment it withdrew.

This is exactly the outcome Ukraine aimed for, and the speed at which a major carrier pulled out shows the strategy is working far earlier than even Kyiv expected. Losing even this handful of compliant, insurable ships pushes Russia toward older, high-risk vessels. With around half of the 500 tankers carrying sanctioned Russian crude being foreign-owned and leased, more companies adopting the same stance would strip Russia of a large share of the fleet that keeps its exports moving.

If every foreign lessor withdrew, Russia would lose access to roughly half of its seaborne oil-export capacity, which translates into more than one hundred billion dollars per year in lost revenue and would erase over a quarter of the federal budget that depends on oil and gas taxes. This exposes the structural weakness of relying on leased tonnage, as Moscow cannot compel it to stay, while Ukraine can convince them of the contrary.

The importance of the Black Sea route makes these shifts even more consequential, as ports such as Novorossiysk and Tuapse previously handled roughly one-fifth of Russia’s seaborne crude and oil-product exports, forming a core component of federal revenue. Oil and gas income still provides roughly one-third of the national budget and around fifteen percent of GDP, making any sustained disruption immediately felt. If insurers restrict trips into the Black Sea and shipowners judge the risks too high, the impact becomes severe. Export volumes fall, Russia grows more dependent on older vessels with weaker compliance records, and each withdrawal introduces new scheduling gaps and revenue instability.

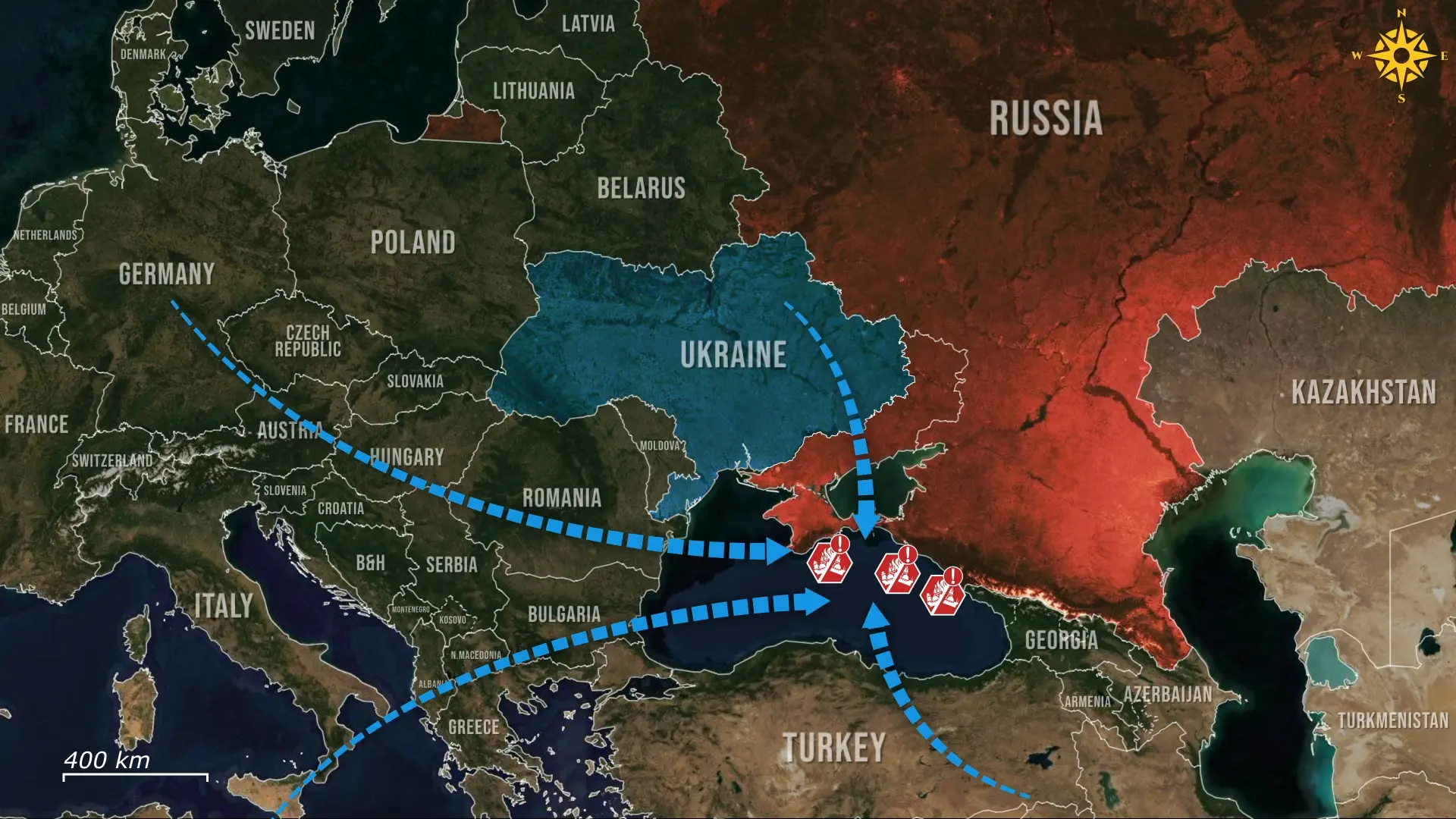

Moscow’s early reaction shows how exposed it feels, because after only two tankers in the Black Sea were destroyed and another damaged off Senegal, President Vladimir Putin publicly threatened to cut Ukraine off from the sea unless the attacks stop. Russian commentators speculated about targeting merchant vessels heading to Ukrainian ports or declaring parts of the Black Sea unsafe for navigation. In practice, these options are extremely limited. Ships supplying Ukraine operate under multiple flags and are insured by Western companies that have already accepted war-risk coverage to keep the corridor open. Any strike on that traffic risks confrontation with states that have avoided direct involvement, including Turkey, which controls the straits Russia still relies on. Escalation at sea would therefore strengthen Ukraine’s position more than Russia’s.

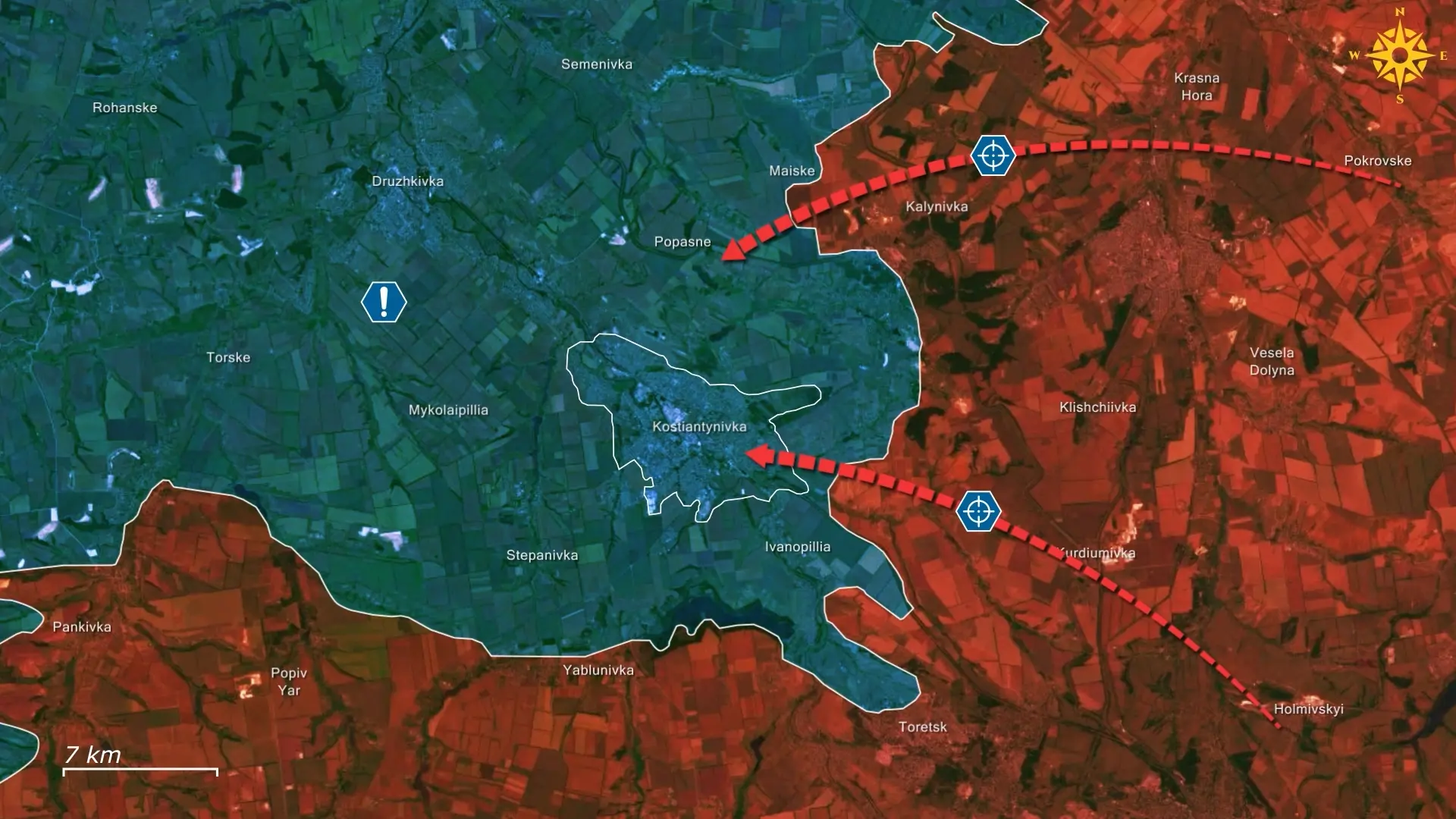

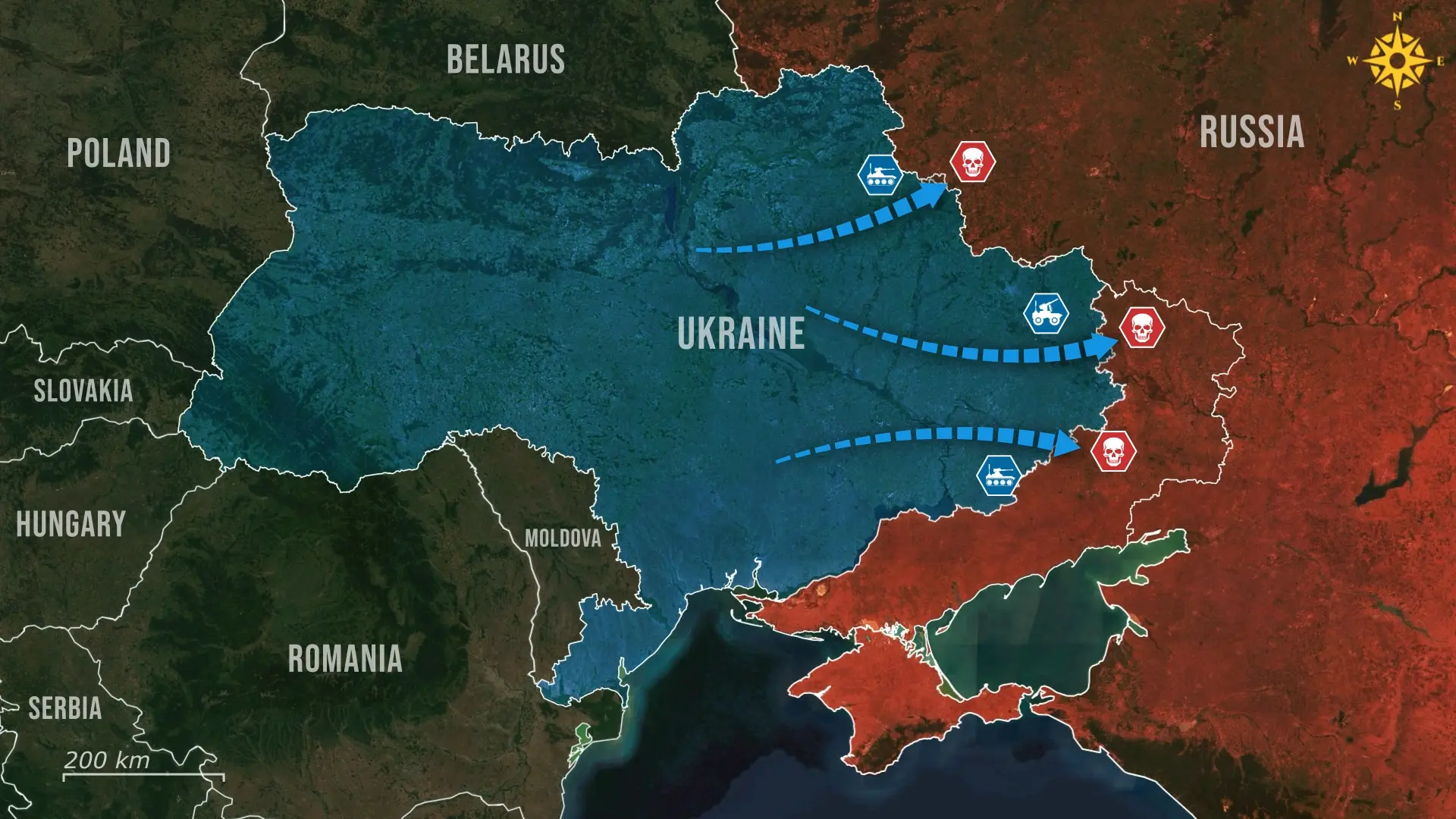

The only alternative would be to remove Ukraine’s ability to stage naval attacks altogether, requiring an offensive toward Odesa or along the southern coast. Yet Russia’s battlefield performance makes this implausible. At the current rate of advance, Russian forces would not reach the administrative border of Donetsk till August 2027. Even with significant manpower deployed, progress remains measured in meters per day in Donetsk, and opening a new front would only further stretch logistics, require contested river crossings, and recreate the vulnerabilities that allowed Ukraine to cripple Russian supply lines during the Kherson counteroffensive. Under current conditions, a move to isolate Odesa would likely create more problems than it solves for the Kremlin.

Overall, Russia’s options are shrinking just as Ukraine’s maritime strategy begins to show results. If Moscow targets commercial shipping, it risks dragging neutral states into the conflict, and if it attempts to cut Ukraine off from the Black Sea, it faces another costly military failure. Meanwhile, shipowners are stepping back, insurers are tightening requirements, and the Black Sea corridor that once carried a major share of Russia’s exports is becoming increasingly unreliable. At the current pace, Russia is on track to lose much of its Black Sea export capacity long before it can mount an effective response.

.jpg)

Comments