Today, the biggest news comes from Europe.

Here, officials are openly acknowledging that the oil price cap on Russian exports is no longer shaping Russia’s behaviour in any meaningful way. What is being framed as a narrow policy change is actually the first indication that Europe is preparing to change how enforcement works at sea.

The European Union is now openly discussing a shift away from the oil price cap and toward a full ban on maritime services supporting Russian oil exports. The focus is no longer on adjusting thresholds or refining compliance rules, but on replacing the price cap framework altogether. In policy terms, this signals that the EU no longer sees the cap as a tool that can be fixed through small changes.

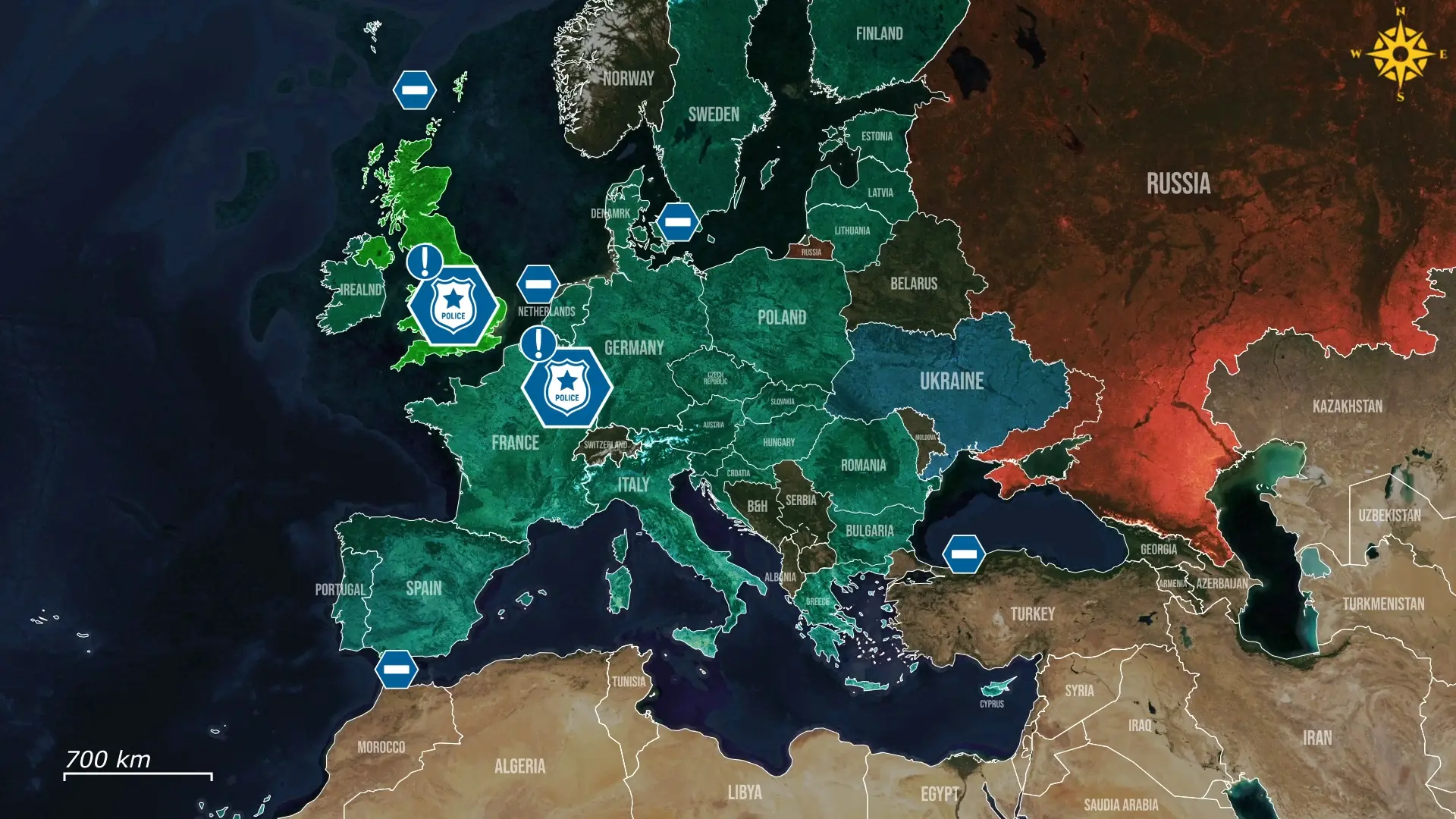

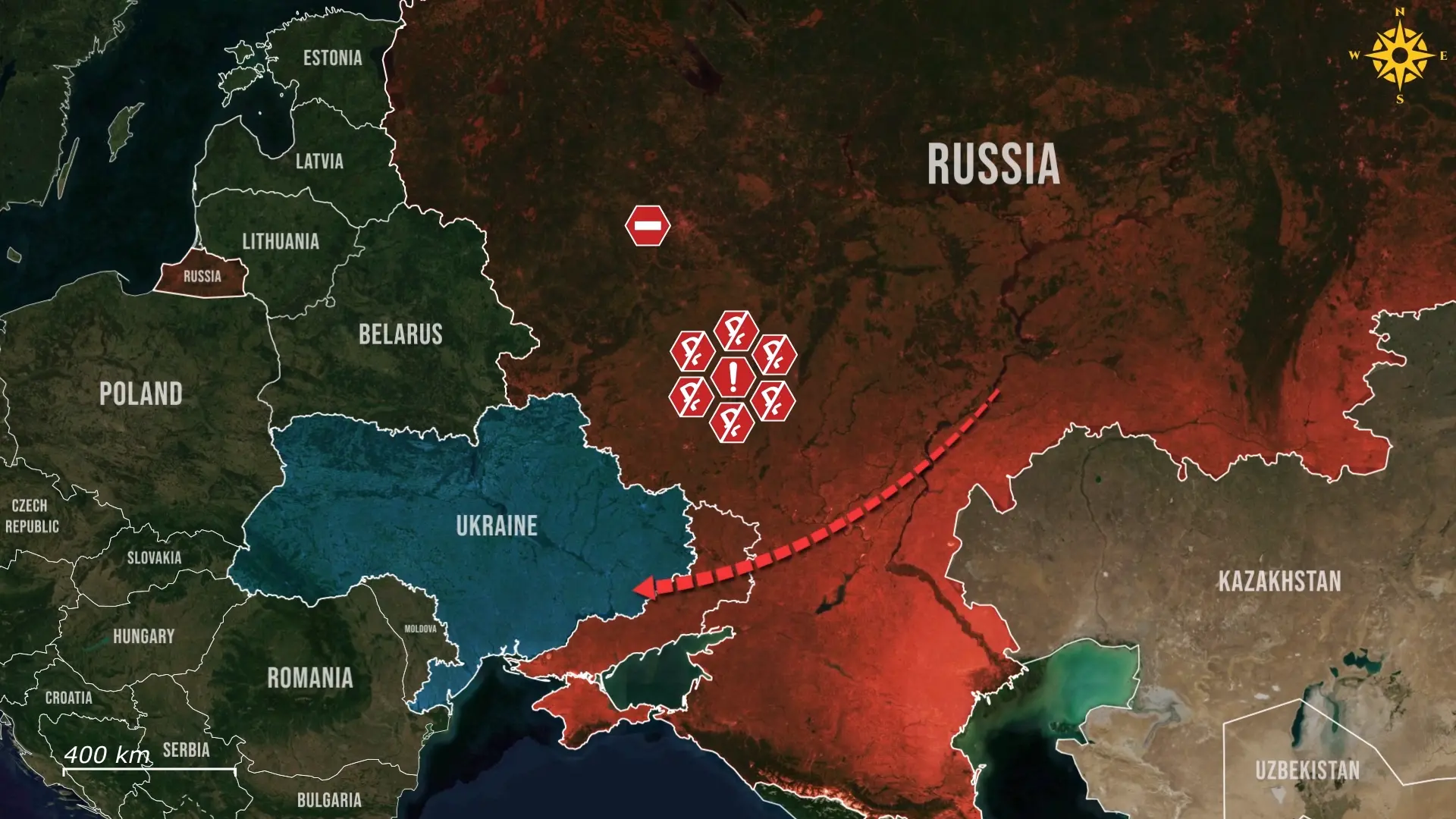

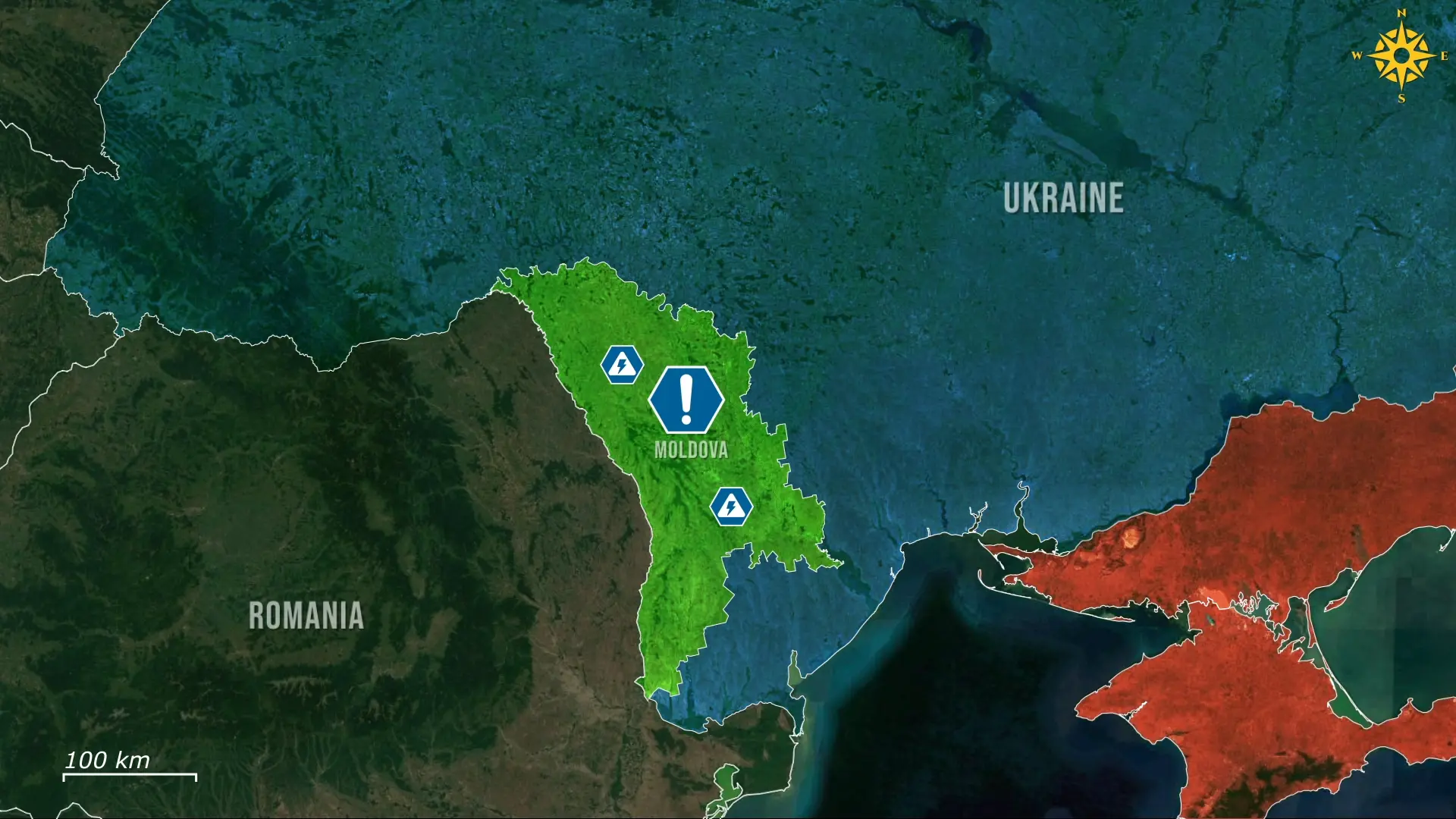

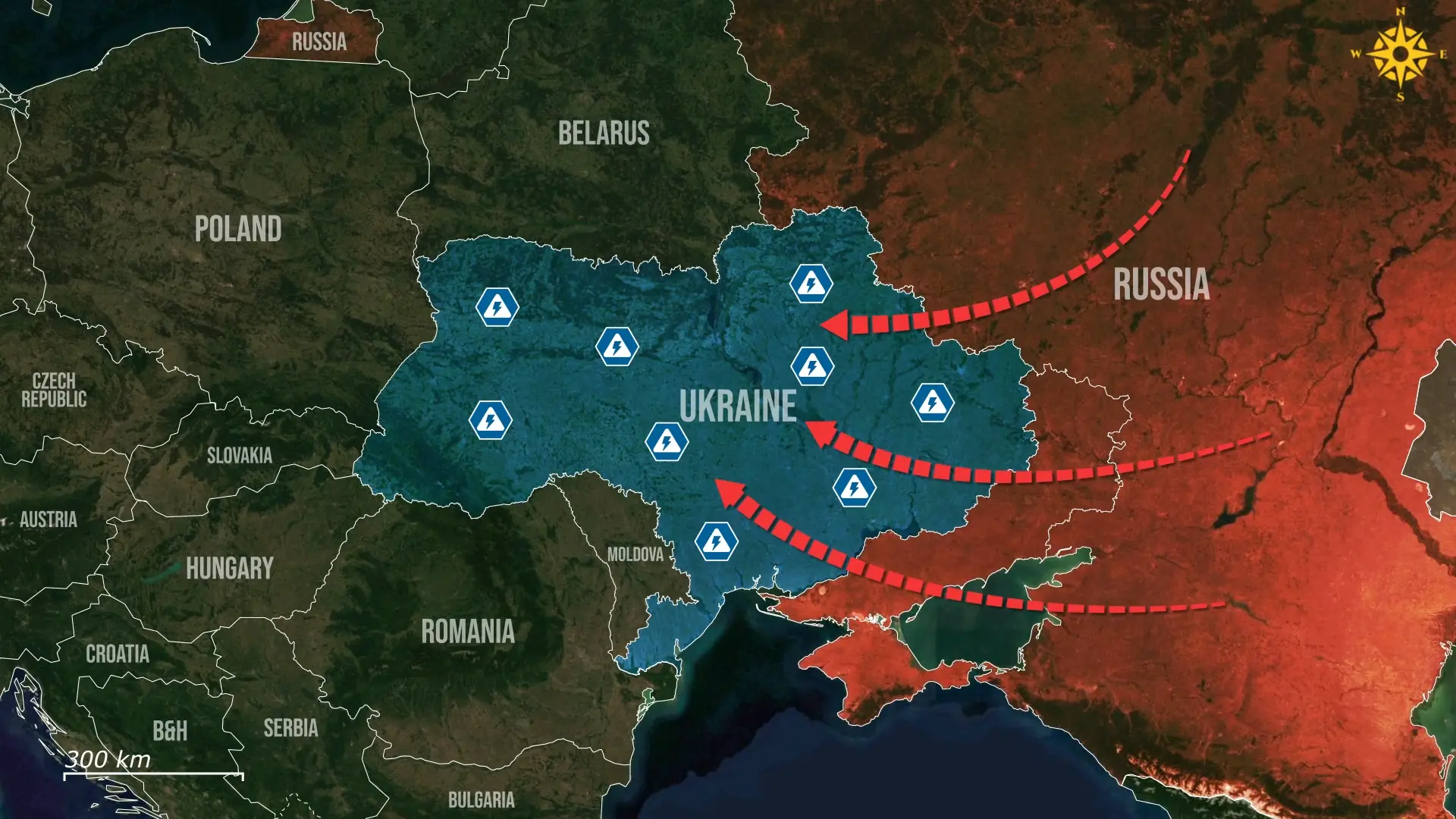

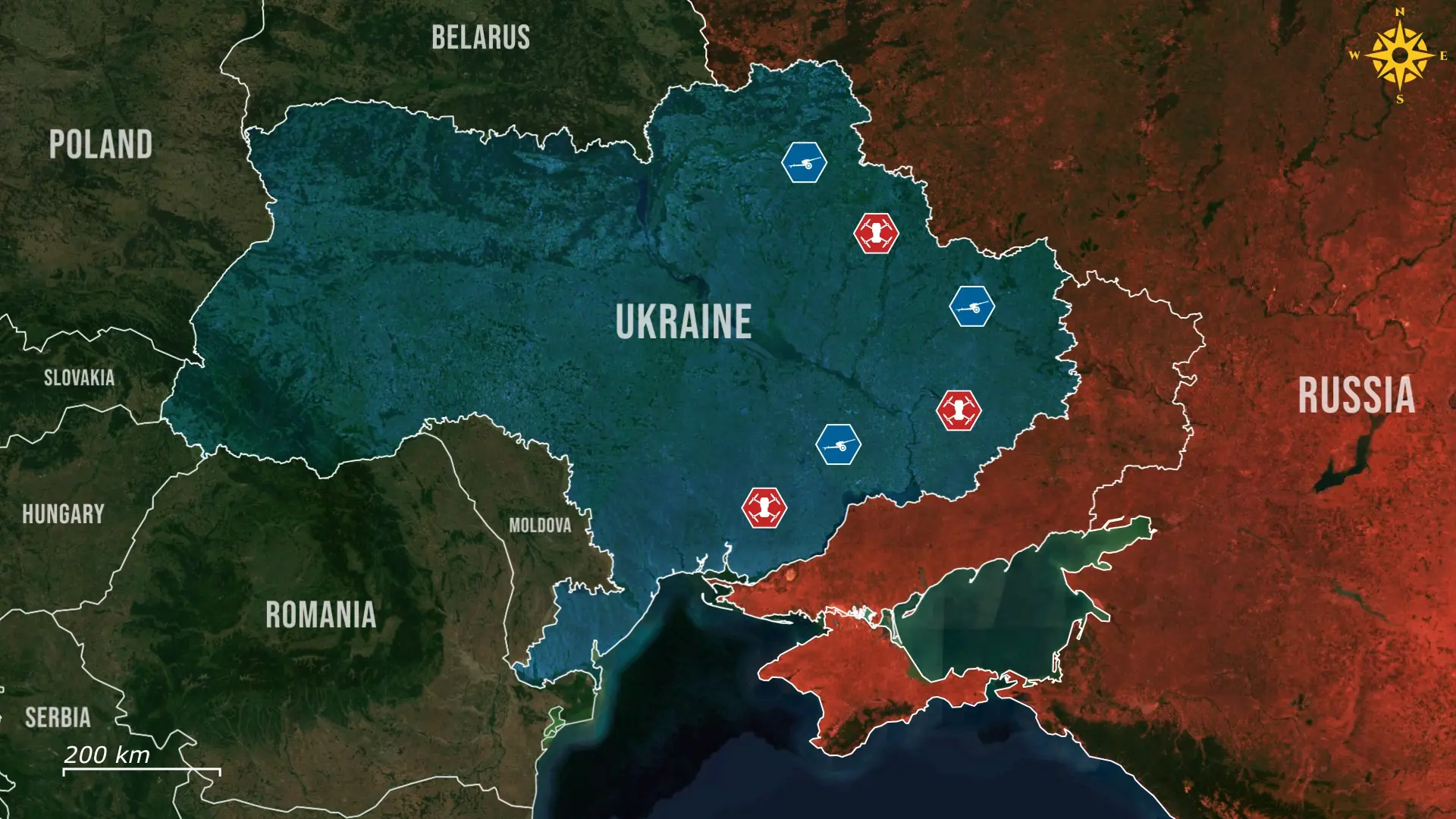

The pressure is growing because Russia’s oil exports are increasingly constrained by a small number of unavoidable sea routes. On paper, the enforcement picture already looks solid. Most Russian seaborne oil exports leave through the Baltic and Black Seas, which means tanker traffic inevitably concentrates into a small number of well-known sea routes.

The UK has said it has the legal basis to stop and inspect shadow fleet tankers transiting the English Channel, and EU officials have stated that if enforcement is activated there, they are prepared to intercept Russian oil shipments and close the Baltic Sea to Russian exports. In theory, this combination should leave Russian exports with few places to hide and give European states the tools to act decisively.

However, enforcement has not crossed that line in practice. The UK, although no longer part of the EU, remains closely aligned with it on sanctions policy and often mirrors EU diplomatic and enforcement positions, yet it is still limiting itself to tracking and monitoring shadow fleet movements instead of routinely stopping vessels in transit.

Spain’s recent actions illustrate the same hesitation, after escorting the sanctioned tanker Chariot Tide out of Spanish waters and into the Moroccan port of Tanger Med instead of detaining it. The ship had lost propulsion near the Spanish coast, and authorities handled the situation as a maritime safety issue instead of using it to enforce sanctions.

This gap between stated authority and actual behavior is precisely why the EU is now considering a more drastic measure, because on paper the tools exist, but in reality states often choose not using them.

Governments are holding back mainly because of legal and financial risks, even though they already understand how Russia is getting around the rules. Boarding or detaining a tanker raises complex questions about maritime law, flag state responsibility, and whether a vessel qualifies as effectively stateless. Detention also exposes governments to lawsuits from ship owners and insurers, as well as liability if an incident leads to environmental damage. In that environment, monitoring feels safer than action, even when enforcement tools technically exist.

This legal hesitation is why the EU and the UK are now moving toward a full ban on maritime services supporting Russian oil exports. The problem with the current system is that enforcement depends on checking prices and paperwork, which gives shadow fleet tankers time to keep moving while authorities hesitate. A full ban cuts through that complexity by setting a simple rule where Russian oil shipped using Western insurance, shipping, or related services is illegal. Under the current system, countries can keep delaying action while they review paperwork and assess compliance.

Under a full ban, that option disappears. If a tanker carrying Russian oil is allowed to pass through their waters without action, authorities are directly allowing illegal activity under their own rules. That flips the pressure completely, because doing nothing becomes the violation. In simple terms, interception stops being a political choice and becomes the basic way governments prove they are enforcing the ban.

Overall, what matters now is less about how the rules are written and more about whether European countries are willing to enforce them. If a full maritime services ban is introduced and followed by the UK, the result will not be an immediate shutdown of Russian oil exports, but growing delays, insurance problems, and higher risks for each shipment.

Over time, that pressure would leave exporters with fewer workable options, either accepting higher costs and exposure or cutting back volumes. The idea is that once ignoring violations becomes costly in its own right, stopping ships becomes the normal response rather than the exception.

.jpg)

Comments