Today, the most significant developments come from Ukraine.

Here, the air war is increasingly shaped not only by missile batteries or fighter jets but by the expanding network of special drone factories that Ukraine and its Western partners are rapidly building. This growing industrial effort is focused on producing thousands of interceptor drones that can counter Russia’s massed aerial attacks and redefine the future of European air defense.

The meaning of this shift becomes clear when we watch the footage of an interceptor drone rising to meet a Russian Shahed. The attacking drone rushes toward a residential high-rise, its engine echoing across the city as it drops to strike at the lowest possible altitude. Then a small Ukrainian interceptor climbs, collides with the intruder, and sends debris falling short of the buildings below. The clip illustrates why these systems are becoming essential, as Ukraine regularly endures nights with more than one hundred incoming drones and must stop them affordably and repeatedly.

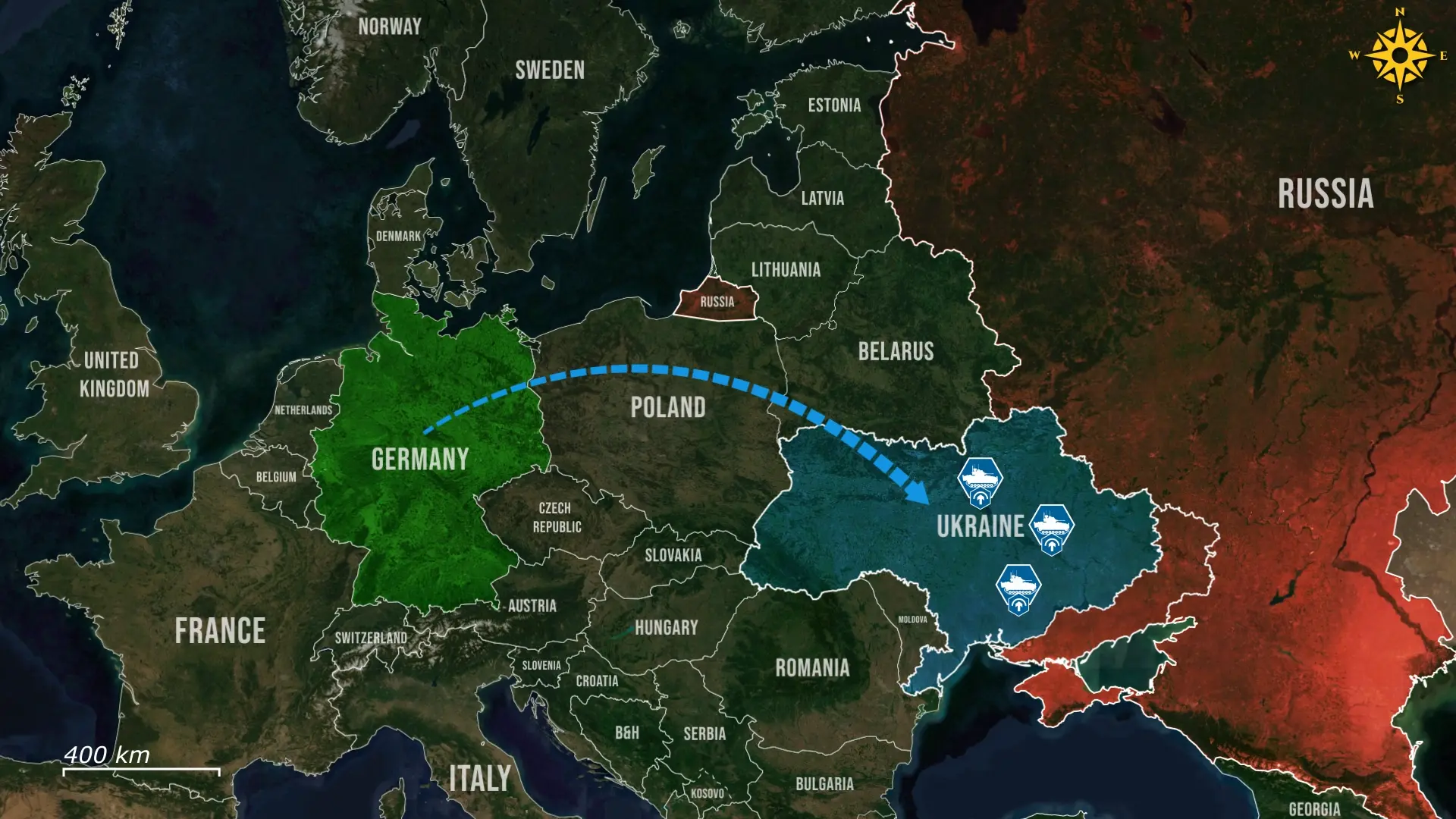

To support this new approach, Ukraine and its partners are rapidly expanding manufacturing capacity. Ukraine needs a constant flow of interceptors to withstand large-scale attacks, while NATO states recognize that similar threats may one day reach their own borders. For that reason, production is spreading beyond Ukraine, with new facilities being prepared in the United Kingdom, Romania, and France. What began as a wartime improvisation is turning into a joint European production base that strengthens Ukraine now and builds long-term defense for NATO.

The partnership between London and Ukraine has become the most advanced element of the international effort. Britain is preparing large-scale production of an interceptor based on Ukraine’s Octopus design, a system proven effective against Shaheds even under jamming and at night. Once the new lines are fully active, the United Kingdom expects to turn out about 2,000 of these drones each month, with early batches delivered directly to Ukrainian air-defense units. This work is supported by major British defense-industrial investments, including a reported 267 million pound investment by a Ukrainian drone manufacturer in UK facilities and a broader UK commitment of more than 4 billion pounds to drone and autonomous-systems manufacturing.

Romania’s cooperation grows from necessity, after repeated incidents of Russian drone debris landing on its territory near the Danube River. Romania and Ukraine have agreed to launch joint production of defensive drones in Romania for Romanian forces, Ukraine, and NATO allies.

Because Romania aims to mirror the British model at a smaller scale and is preparing a single joint assembly line under the EU SAFE program, a reasonable estimate is that Romanian facilities could reach a monthly output of 500 to 800 interceptor drones. The program fits within Romania’s broader rearmament plan, which is backed by an estimated 16.6 billion euro EU safe-program allocation over five years.

France adds a high-tech layer through the X-Wing interceptor developed by Alta Ares with Ukrainian engineers. The system uses advanced AI guidance and has already demonstrated strong performance in NATO testing. It has also been tested by Ukrainian units against Shaheds, FPV drones, and guided bombs, proving it can handle a wide variety of threats in real combat conditions. Mass production has begun in France, with plans to localize part of the process in Ukraine. Although France has not released specific production numbers, the size of the Alta Ares facility and the company's stated shift to mass production indicate a likely output of 300 to 500 X-Wing interceptors per month.

At the center of everything lies Ukraine’s rapidly growing industrial base. Several domestic manufacturers are already producing interceptor drones, with more than ten additional companies preparing to join them. The goal is to reach 600 to 800 interceptor drones per day by the end of November 2025, and eventually scale toward 1,000 units daily, providing a sustainable supply to counter Russia’s large-scale drone assaults. At that pace, Ukrainian factories alone could produce around 30,000 interceptors per month. Russian Shahed output, according to Ukrainian and Western estimates, ranges from roughly 2,700 to around 5,000 per month, depending on the phase of the ramp-up.

If Ukraine reaches even half of its target, it would still generate several times more interceptors than Russia produces Shaheds, even before counting British, Romanian, and French contributions. As production accelerates, Ukraine is expected to provide the majority of its own interceptors, while allied output offers redundancy, surge capacity, and long-term security for both Ukraine and NATO.

Overall, this growing production network marks a major shift in how modern air defense is supplied and sustained. Ukraine and its partners are now building an industrial system that is fast, adaptable, and resilient enough to withstand large aerial attacks. The combined efforts of Ukrainian factories and Western production lines give both Ukraine and NATO the ability to meet future threats with confidence rather than improvisation. Each new interceptor emerging from Kyiv, Birmingham, Bucharest, or Bordeaux strengthens not only Ukraine’s defense today but also the long-term stability of Europe’s airspace.

.jpg)

Comments