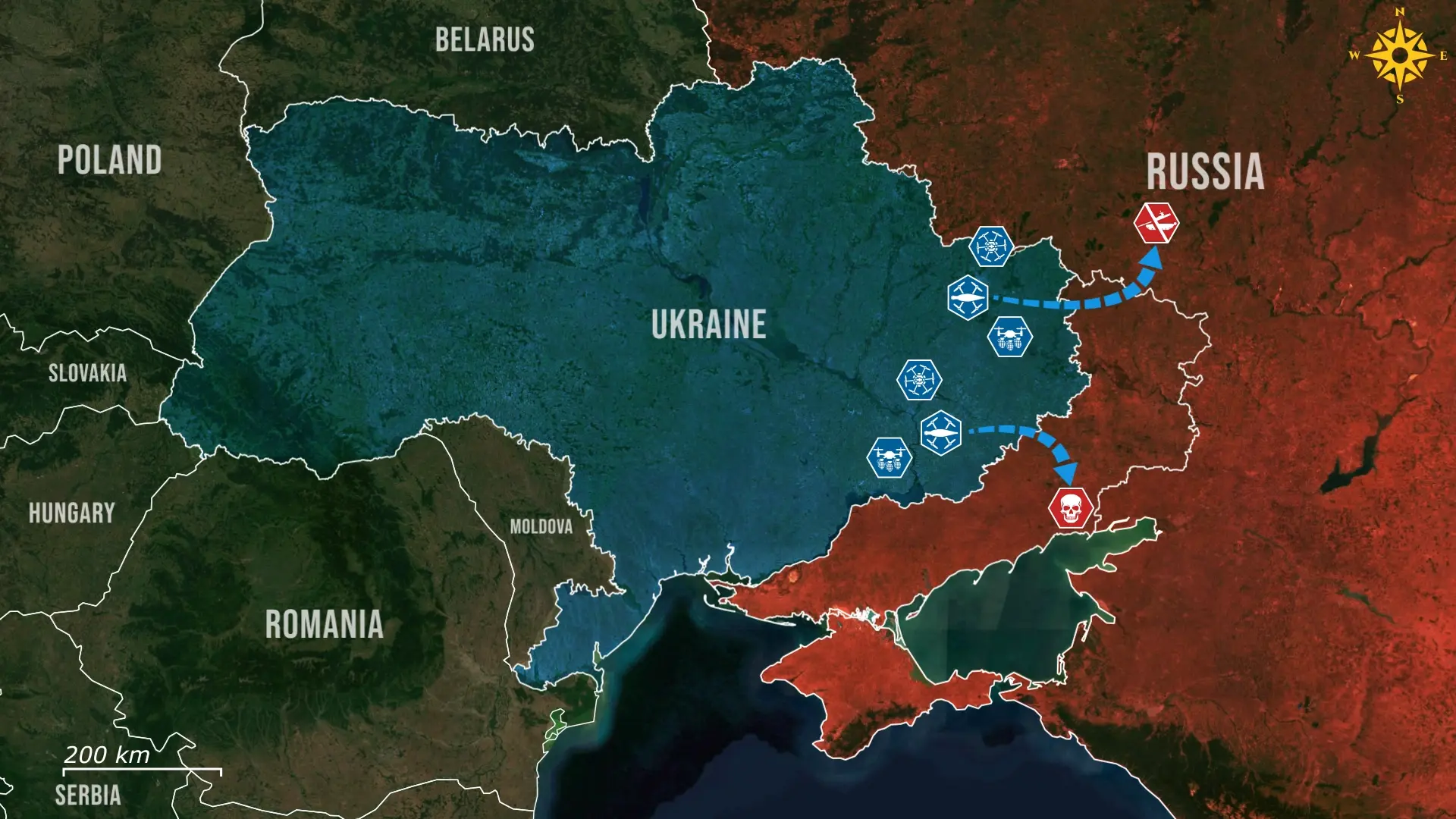

Recently, Ukrainian drone strikes have become more frequent, more coordinated, and harder to intercept. While Russian forces have used everything from small arms to advanced fighters to shoot them down, success remains inconsistent. But beneath that inconsistency lies a deeper problem: Russia’s fighter jets were never built or equipped for this kind of war.

Ukraine is ramping up drone strikes on oil infrastructure, airfields, air defense, and military factory across Russia.

To stop them, Russia scrambles fighters like the Su-30-SM and MiG-29 to intercept incoming drones. Jets are engaging targets at low altitudes with cannon bursts, but these improvisations reveal the underlying problem.

Unlike the United States, which arms its aircraft with Sniper Advanced Targeting Pods, or France with the Thales Damocles system, Russia lacks a widely deployed equivalent. A few pods were tested in Syria and exported to Algeria, but they are rare in domestic service. This leaves Russian pilots flying practically blind, especially at night or in poor weather.

A stark example is India, which operates Russian-made SU-30 fighter jets with Israeli Litening targeting pods, providing infrared sensors, laser designation, and night vision targeting.

By contrast, Russian pilots still often rely on helmet sights and visual contact, highlighting how Russia’s air forces are flying less-capable versions of the same aircraft than the nations to which they exported them to.

The shortfall stems partly from sanctions. Modern targeting pods require advanced microchips, thermal cameras, and stabilized optics. These are hard to produce domestically at scale. Russia has been able to evade sanctions and buy from Asian countries to fill some gaps, but not enough to support high-volume production, as these components are also critical for other weapon production. More importantly, Russia’s defense sector was not prioritizing pod development even before the war. Advanced kits like the Sapsan-E were shelved or delayed, resulting in limited production lines and jets taking off for high-stakes missions without modern sensor packages.

Another issue is Russia’s long tradition of choosing simple, rugged equipment over advanced technology. In Syria, Russian bombers dropped unguided munitions from high altitudes, often with little accuracy.

This was not due to necessity; they could have used better targeting kits, but because their doctrine favors durable, low-tech solutions. That same mindset appears in Ukraine. Russian jets have reportedly missed drone targets in broad daylight.

One example is a 2023 incident near Berdyansk, where a Su-30 repeatedly failed to intercept a quadcopter loitering over an airbase.

Faced with these limitations, Russian pilots rely on weapons like the R-73 missile. This is an infrared-guided missile designed for short-range dogfights. To use it, the pilot must visually acquire the target, line up the seeker, and lock on. Without targeting pods, the engagement range shrinks dramatically. Jets have to fly dangerously close, giving drones more time to evade or complete their mission. This wastes time, fuel, and ammunition, making each interception far more expensive and inefficient than it should be. Even if the missile connects, it is an expensive trade, firing a 250,000 dollar weapon at a 20,000 dollar drone.

However, there are no indications that Russia is about to start mass production of these targeting pods. Instead, Moscow appears to be investing in ground-based electronic warfare, radar-guided guns, and layered air defense networks. These systems are more cost-effective and do not rely on restricted technology; however, they do not fulfill the role of fighter jets in air defense. Drones operating at treetop height can slip through radar gaps, and ground teams are often already the last line of defense.

Overall, Russia’s failure to equip its fighter jets with targeting pods exposes a dangerous vulnerability in modern Russian warfare and air defense. The problem is not just about drones getting through; Russia exports combat platforms that are more capable abroad than at home. It speaks to a deeper issue, not just technical, but strategic. A military that builds for durability and ignores sophistication in its weapon systems may win conventional wars by brute force, but the modern reality of drone warfare demands something else: vision, adaptability, and efficiency. If Russian jets cannot reliably stop Ukrainian long-range drones, then even the most expensive fighters become reactive platforms, chasing shadows. And in a war of attrition, that is not only inefficient, but also unsustainable.

.jpg)

Comments