Today, the biggest news comes from the Russian Federation.

Here, Russia, with its vast oilfields and long-standing resource-export economy, has now become an importer of refined fuel, buying gasoline to fill holes in a domestic system that can no longer turn crude into petrol and diesel. The heaps of damaged refineries have led Russia to impose emergency tariff changes, seize oligarch’s energy assets, and overall move to last-resort measures.

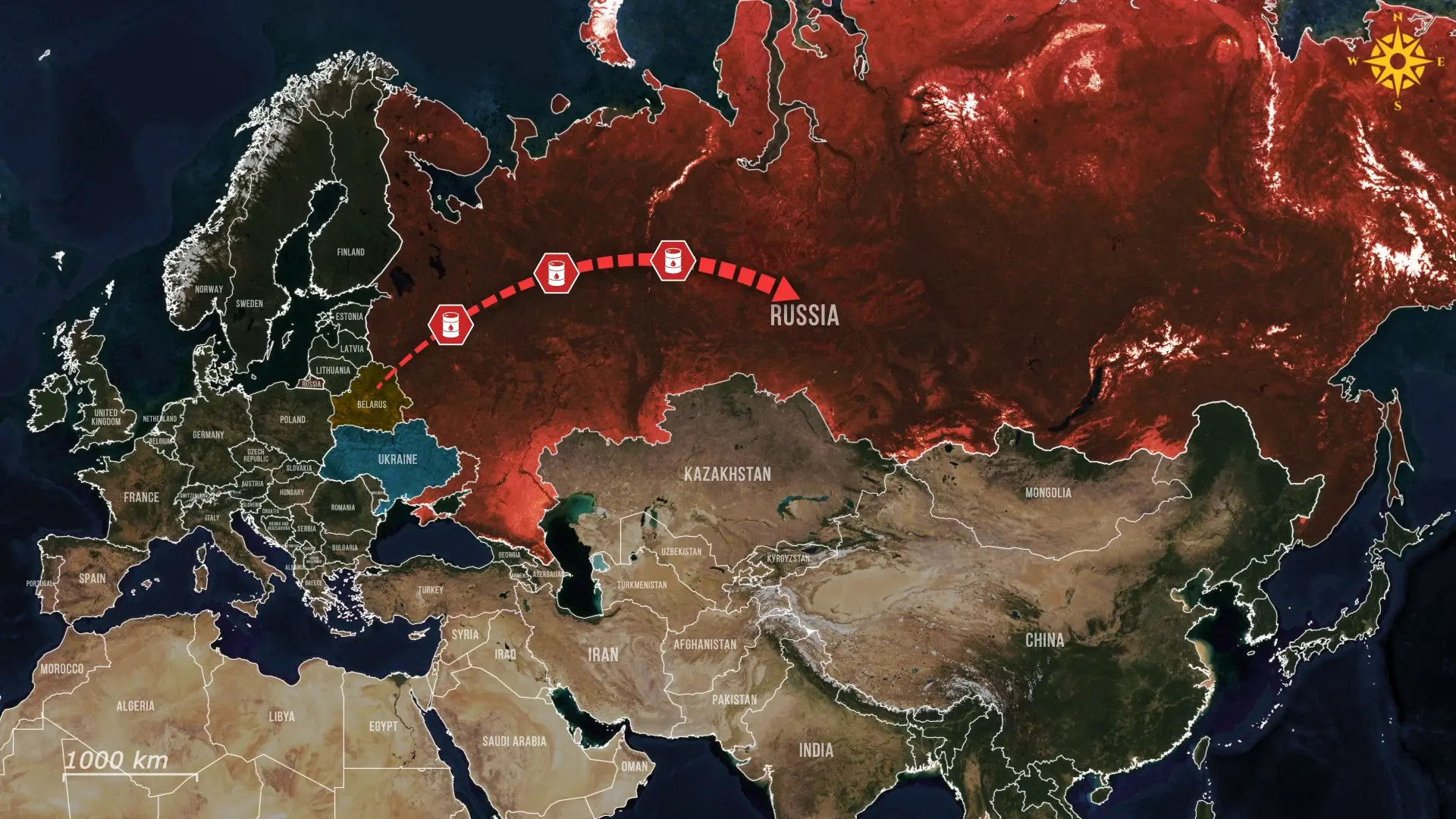

Russia’s slide into dependence began with a simple, uncomfortable fact that refined product flows are collapsing. In September, Belarus ramped rail deliveries to Russia roughly fourfold, sending about 49,000 tons of gasoline into Russian markets as Kremlin officials scrambled to plug holes left by repeated strikes on processing hubs.

Those Belarus rail shipments and other short-term imports blunt immediate shortages at pumps, but they do not replace lost refining capacity, as once again, regional storage and processing gaps widen, even large imports only stack over shortages and leave systematic shortfalls in place. With those emergency imports temporarily in place, Moscow took the next set of extraordinary steps. Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak publicly backed removing or cutting import duties on gasoline brought in from Asia and elsewhere, as abolishing import duties was a deliberate move to speed private gasoline into Russian markets. The policy move lowers the price floor for private importers and accelerates private-sector shipments into Russian distribution channels, but it also signals a loss of confidence in the country’s refining base and a willingness to use the market to mask a strategic shortfall.

As imports and duty changes failed to stabilize supplies quickly, and market fixes did not restore steady supplies fast enough, Moscow moved to more desperate political measures, forcibly seizing Oblkomun-energo from two billionaire oligarchs and reassigning the company to state control. The giant previously specialized in the dealings and maintenance of the Russian energy market based out of the Urals, providing electricity to civilians, businesses, and organizations alike. Seizures and leadership changes are presented as emergency fixes, and a part of the Russian state’s desperate attempts to gain a more direct grip on the problems the country faces, but they carry a dangerous precedent. More importantly, oligarchs are not mere businessmen but part of the behind the scenes network that run Russia; forcing them to surrender assets is politically risky, since those networks will only tolerate so much pressure before they slow cooperation or push back.

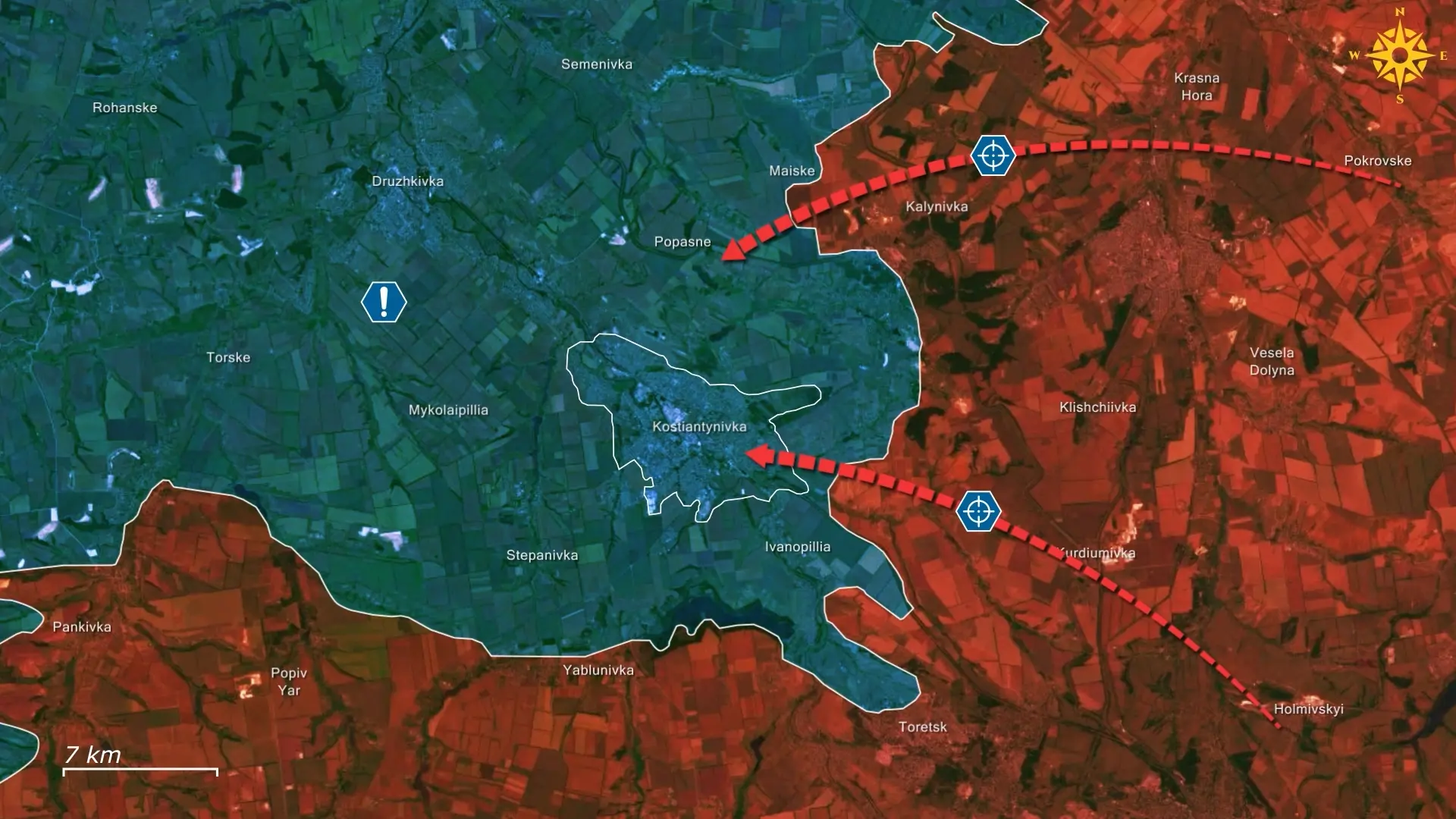

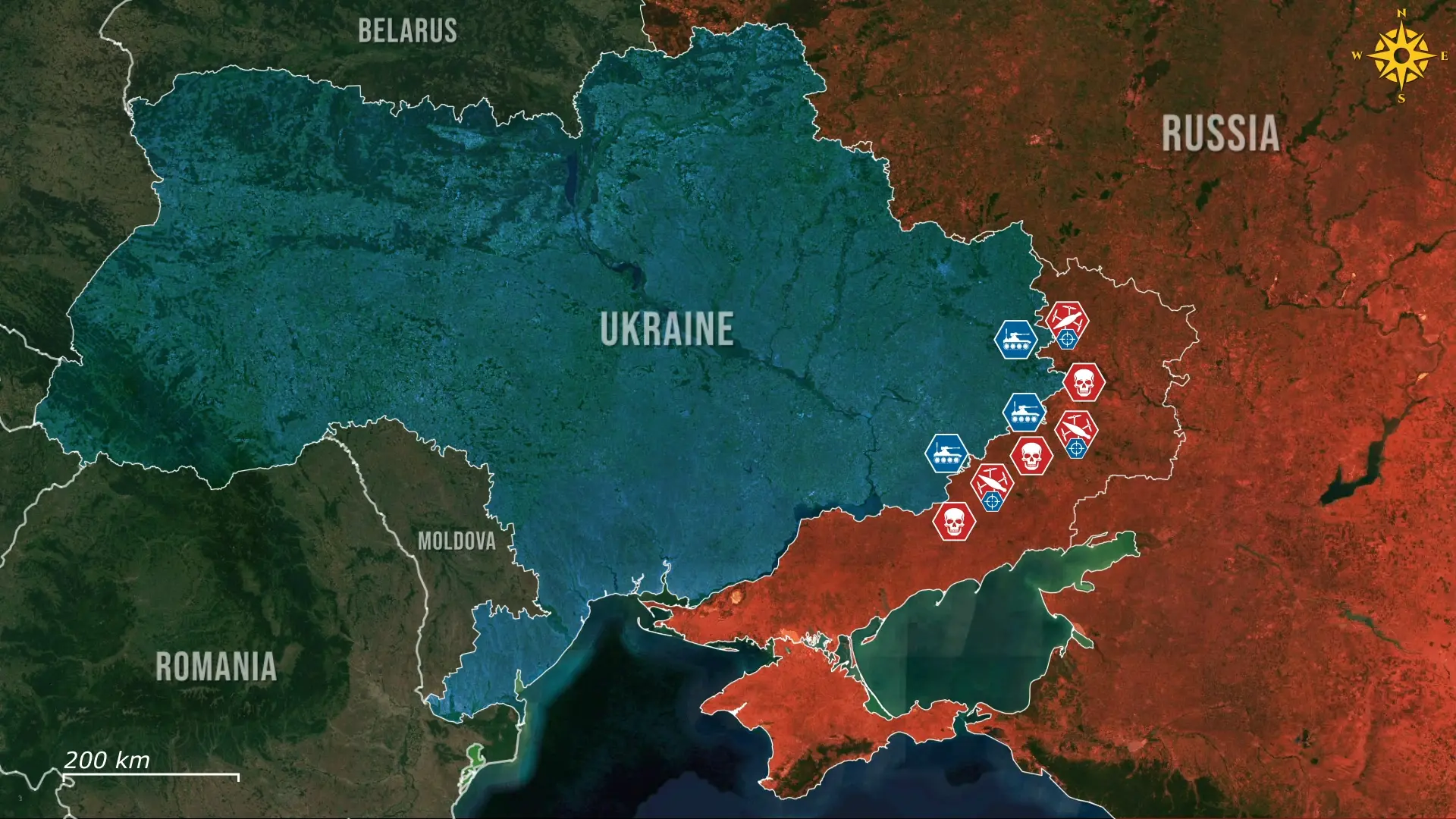

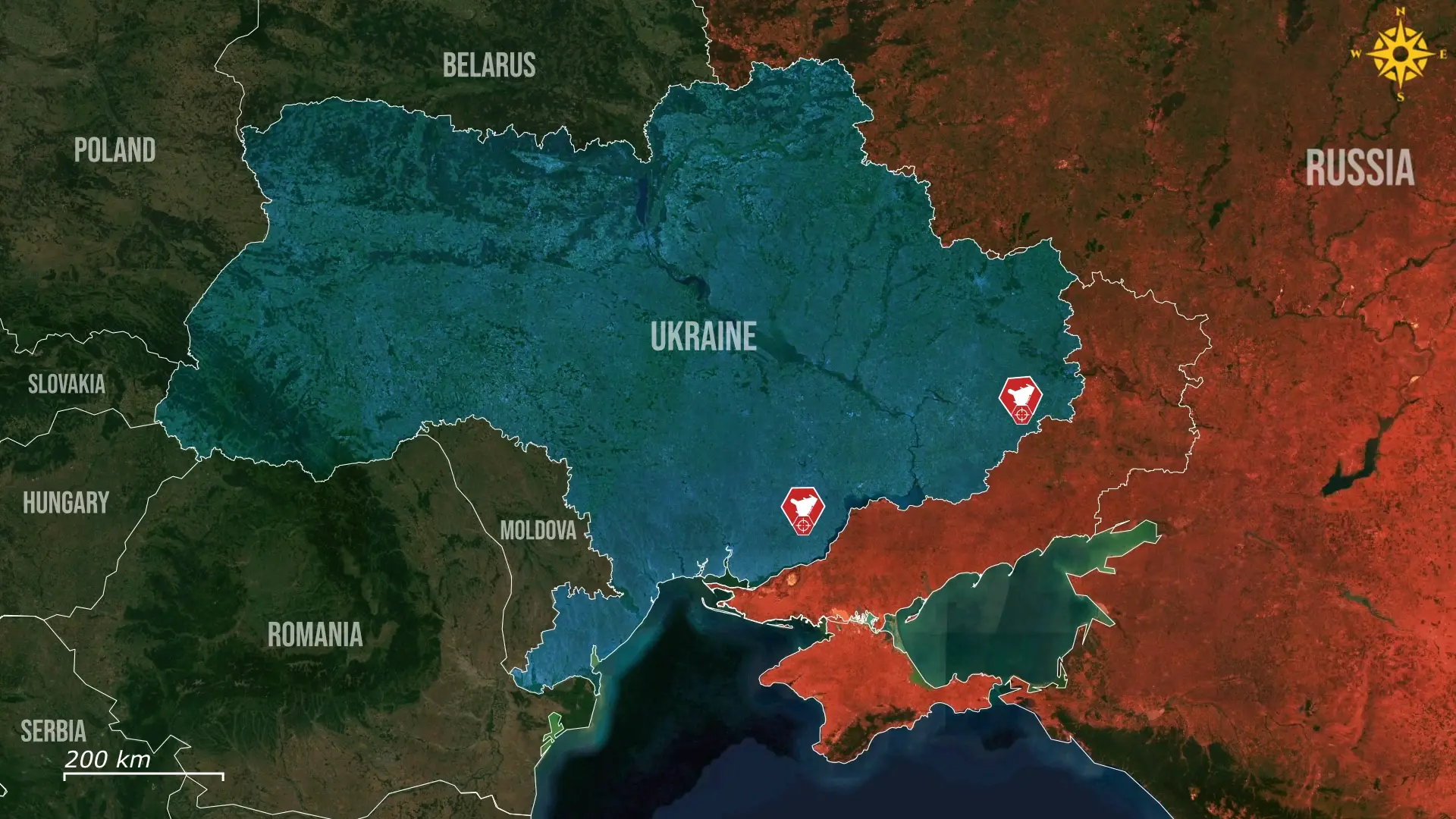

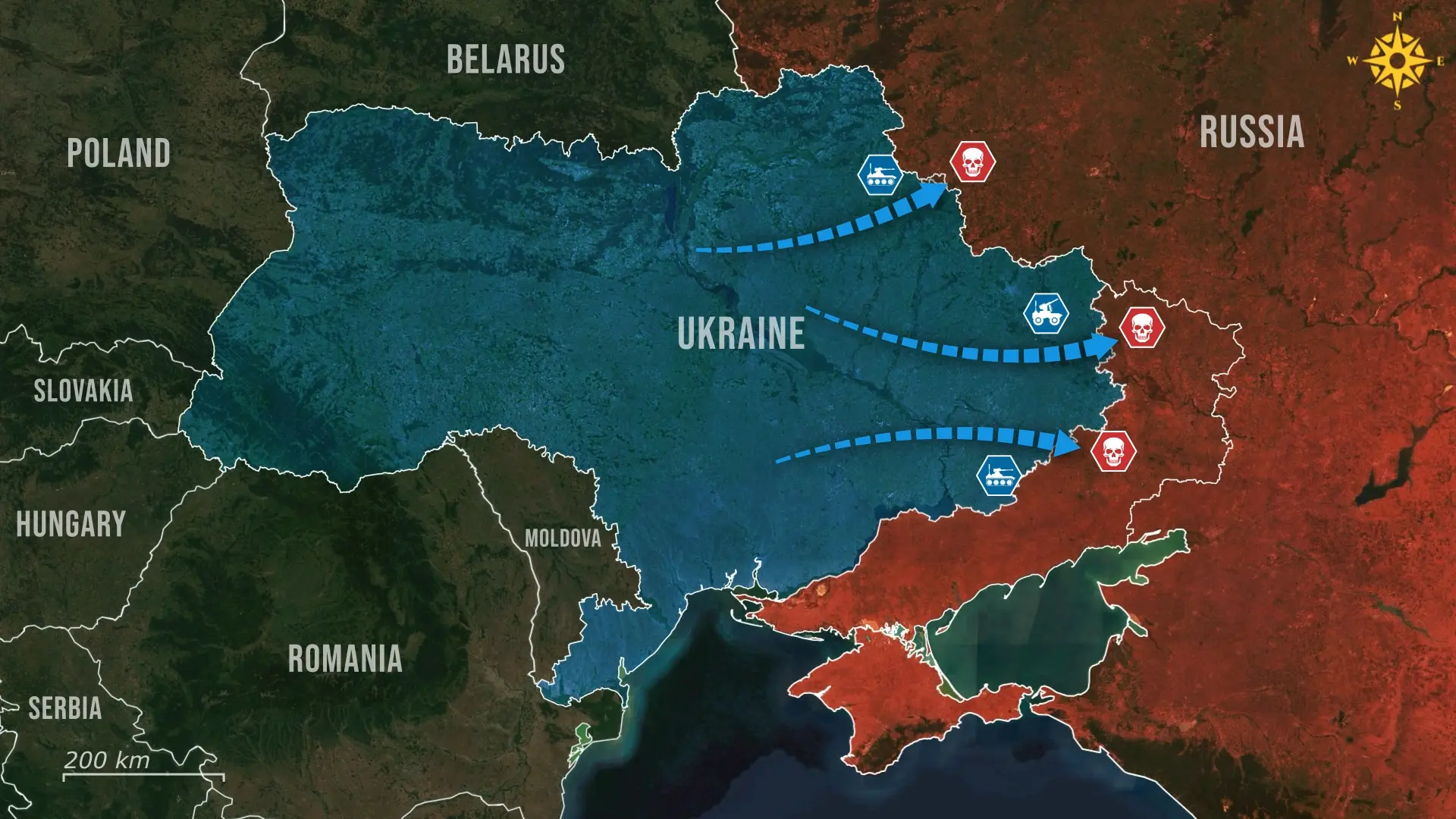

Russia, the world’s energy superpower, has quietly become a buyer of refined fuel, as Belarus rail deliveries surged to roughly 49,000 tonnes in September to plug holes at regional pumps, a stark reversal for a nation built on vast oil fields. The cause is a stepped-up strike campaign: officials, including Rustem Umerov, say Ukraine will scale attacks on logistics and fuel infrastructure and open reporting now records hits on oil facilities every one to two days.

The effects are visible on the ground, as Belgorod gas stations ban jerrycans so residents cannot refill generators, Gazprom pumps in Volgograd reports no supply, while Yar-Neft and Volga-Neft are out of gasoline, and occupied Donetsk shows long queues as 92 and 95 octane fuels disappear. With 16 of Russia’s 38 refineries hit in recent weeks and refined-product export down by about 170,000 barrels per day, pipelines, rail, and port schedules cannot be rewired overnight, and imports only paper over lost processing capacity. For the policy gambit to work, seized companies must deliver spare parts, engineers, and sustained maintenance. If they do not, ownership changes will be cosmetic, and Russia will face a prolonged fiscal squeeze and deeper rationing at home.

Overall, these emergency measures read less like clever policy and more like the last stage of crisis management: a market patch, a tariff lifeline, then direct state control when both fail. That sequence shows the Kremlin’s shrinking toolkit, and it raises an uncomfortable question for policymakers and markets alike: if physical refining capacity stays impaired, short-term fixes will keep costs high and revenues low, and Russia’s role in global refined-product markets will be fundamentally altered.

.jpg)

Comments