Today, the biggest news comes from the Russian Federation.

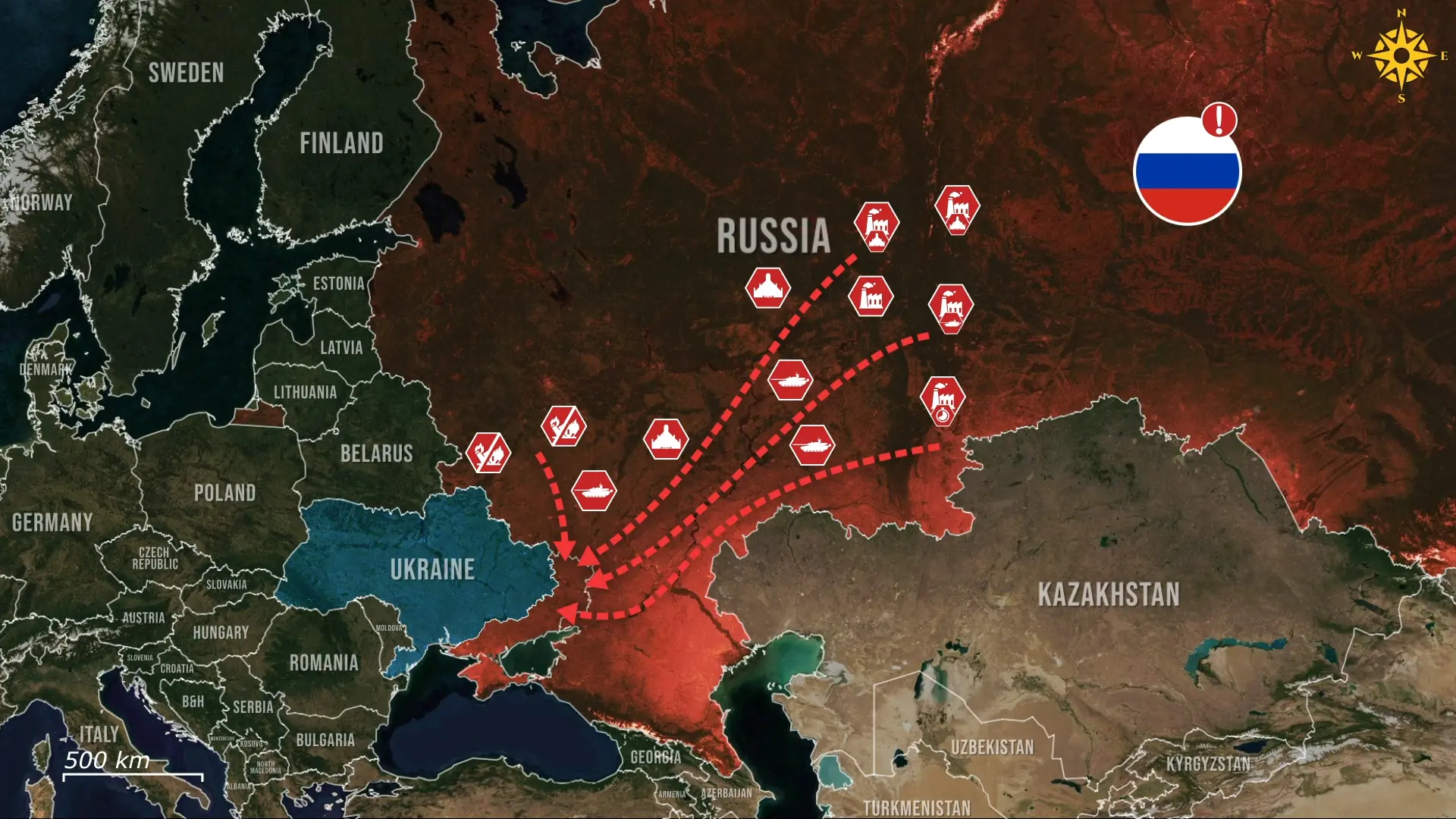

Here, Russia’s largest tank producer has begun mass layoffs, a stunning reversal for a nation that claims to be building a war economy capable of outproducing Ukraine and the West. The move signals deep strain at the heart of Russia’s defense industry and raises doubts about how long it can sustain large-scale production.

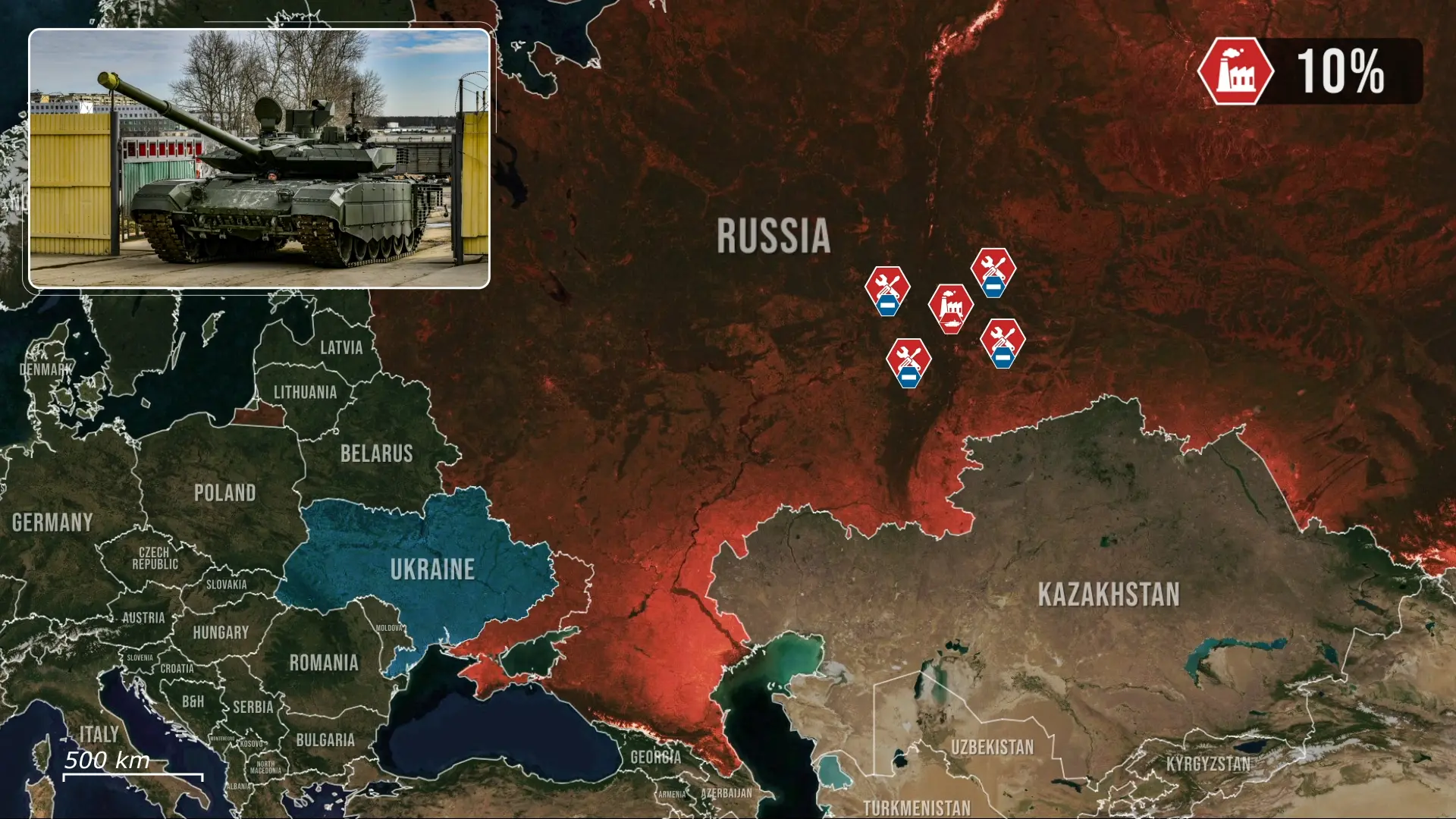

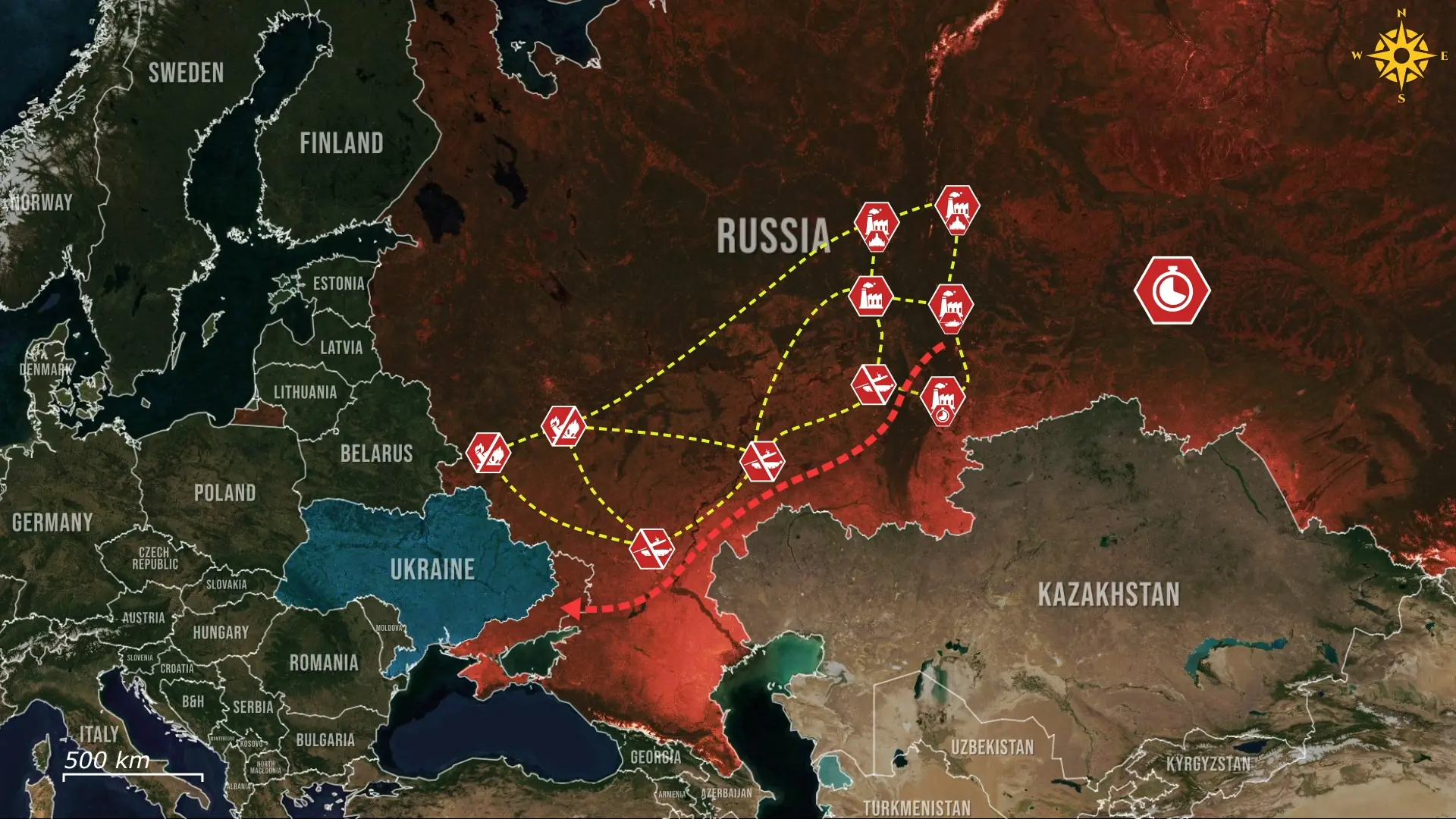

Russia’s main tank manufacturer, Ural-vagon-zavod, has announced layoffs of roughly ten percent of its workforce and a freeze on new hires until February, with some internal divisions reportedly losing up to half their staff. The cuts go far beyond administrative reshuffling, as insiders cite a combination of crippling factors: sanctions that block imports of Western optics and fire-control systems, exhaustion of stored spare parts, and delayed state payments for ongoing contracts. The company is already behind on deliveries of T-90M and T-72B3 tanks, with workshop activity down by nearly 33% compared to last winter. It’s a chain reaction: without foreign components, upgrades stall; without upgrades, contracts shrink; and without new contracts, entire divisions begin to shut down.

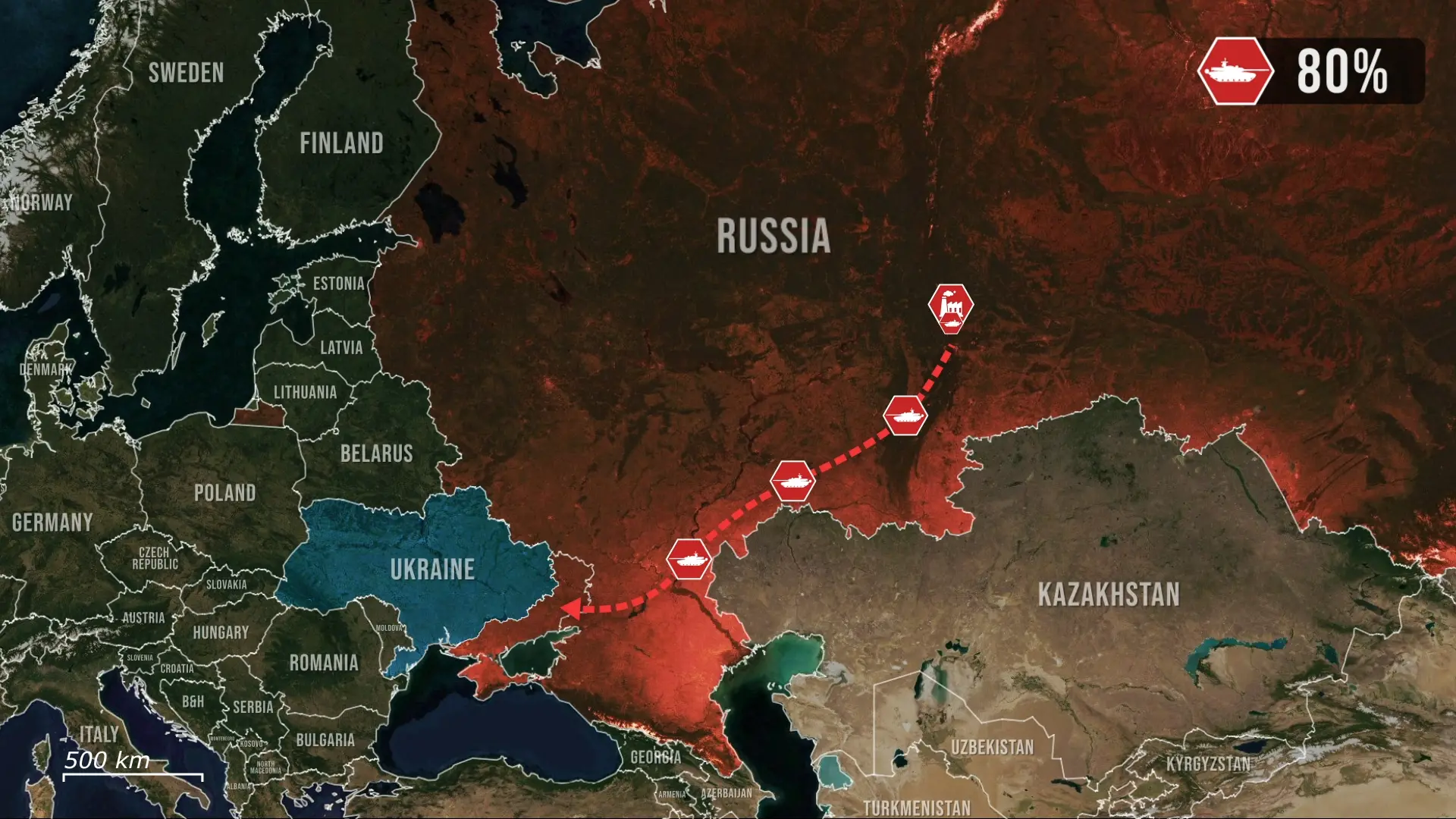

The consequences reach far beyond one factory, as Ural-vagon-zavod, builds and repairs most of Russia’s main battle tanks, including the T-90M and T-72 series that form nearly 80 percent of its active armored fleet. Even a modest ten percent reduction in staff could mean 25 to 30 fewer tanks repaired or produced each month, enough to reduce frontline availability by hundreds over a single year.

The reported 50 percent layoffs in some divisions would push output back to pre-war levels, erasing two years of industrial mobilization. Russia has already been losing armored vehicles faster than it can replace them. What is changing now is that they lose the ability to rebuild reserves for massed assaults altogether.

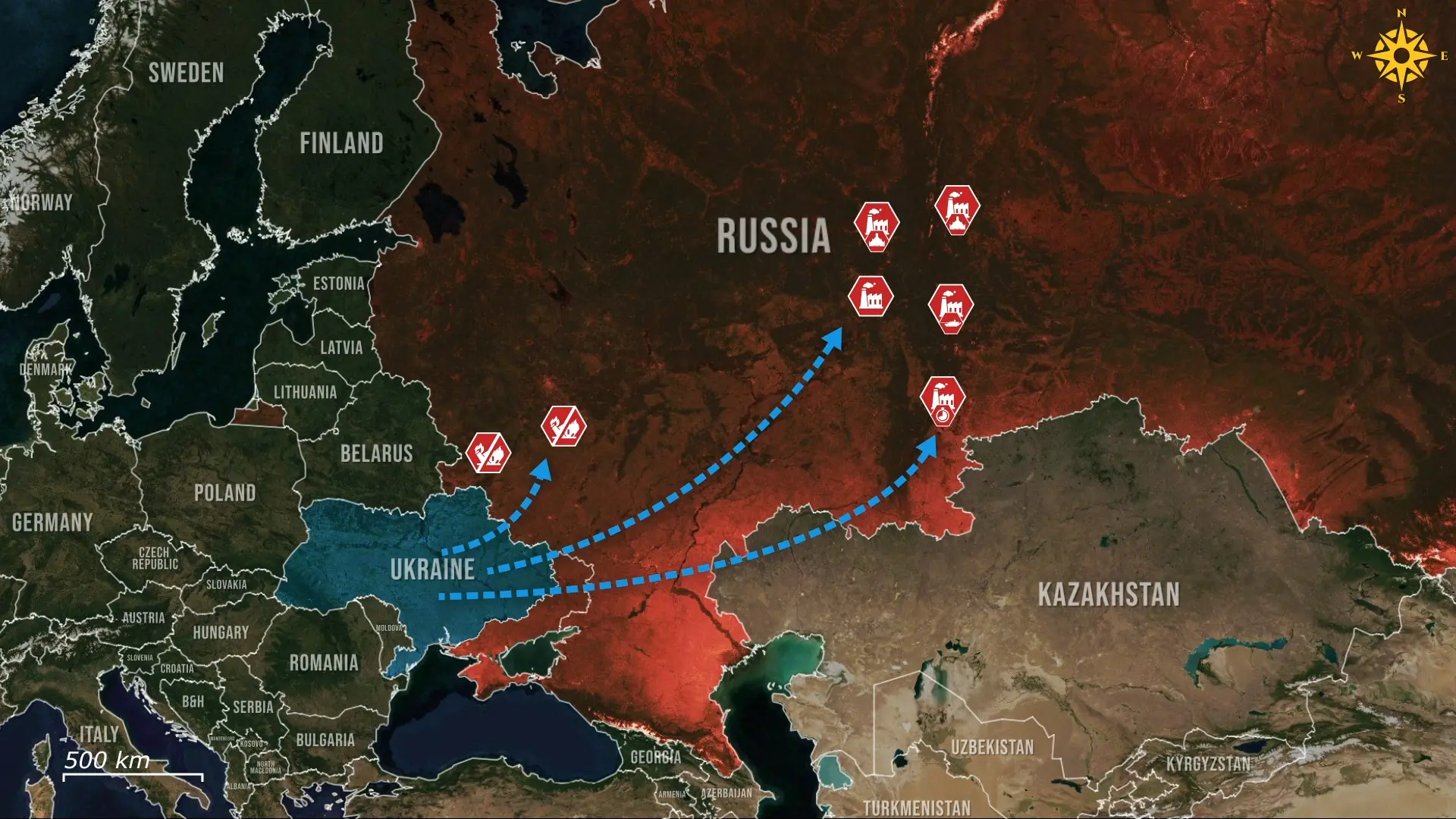

The layoffs also highlight a problem at the core of Russia’s war economy, as Moscow is short nearly 5 million workers across key sectors, according to official estimates, and defense plants are among the hardest hit. Skilled welders, machinists, and engineers have been drafted or have fled abroad, while those who remain are aging and overworked, with Russia not having enough to fill the heightened demand. Entire industrial regions from Nizhny Tagil to Ufa now offer 40 to 60 percent wage bonuses and still fail to fill vacancies. The fact that Ural-vagon-zavod is cutting jobs instead of hoarding them shows the problem is not labor, but resources: a major red flag, as it signals that Russia’s production system is running out of both money and metal.

The plant may have workers, but without imported electronics, high-grade alloys, or Western machine tools, those workers have little to build. As sanctions continue to bite, the cost of replacement parts and foreign components has skyrocketed, forcing factories to idle production lines they can no longer afford to operate. In many cases, layoffs are a disguised form of shutdown, a way to quietly freeze activity without admitting bankruptcy.

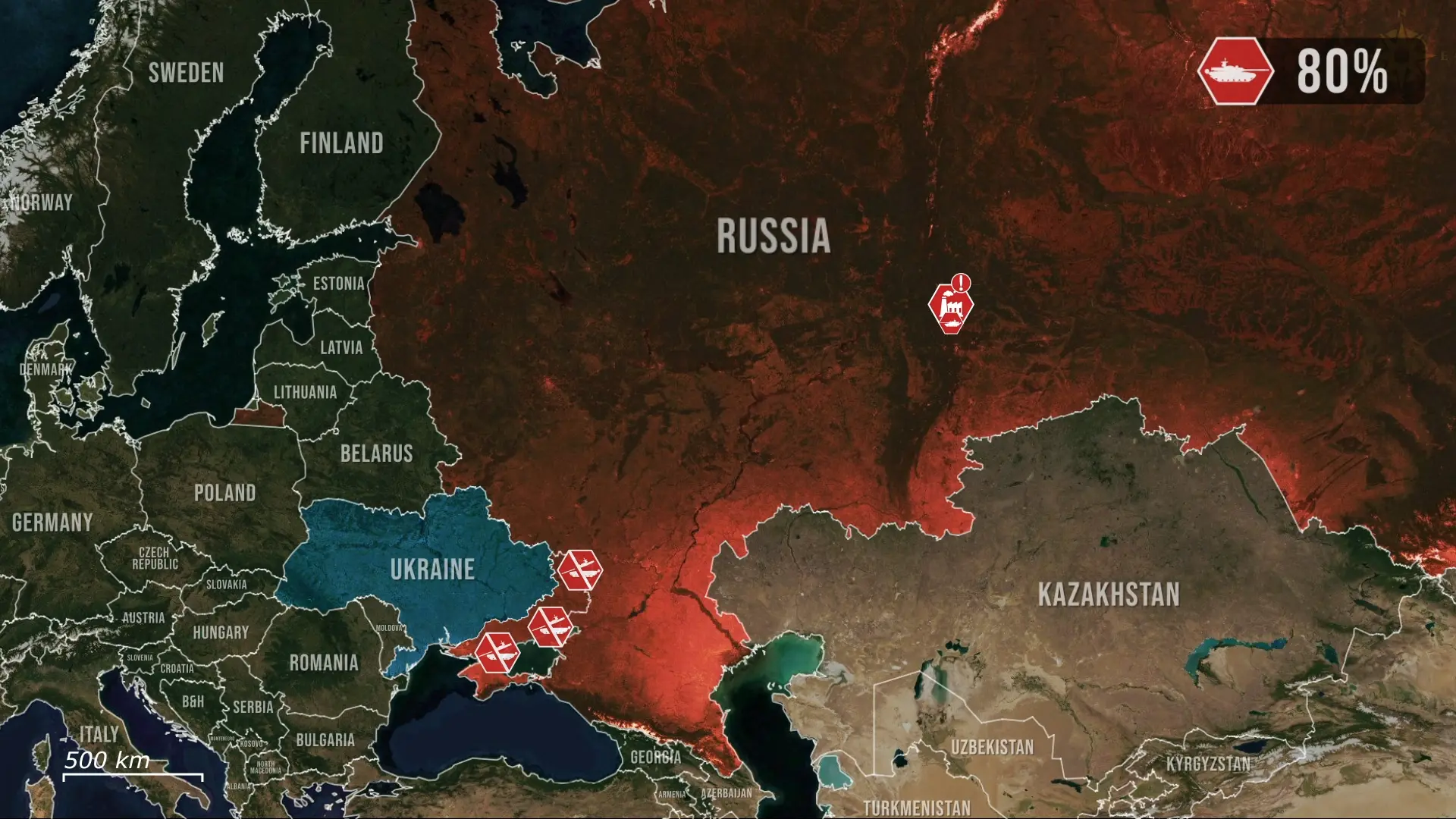

The same pattern is emerging elsewhere, as in Tula and Bryansk, small-arms and component plants have halted production several days each week due to missing parts and unpaid contracts. Workers in Izhevsk report wage delays of up to two months. Ammunition factories in the Urals, which had been running 24-hour shifts, are now cutting back to two. Even the aerospace sector, long prioritized for funding, is postponing engine deliveries for drones and cruise missiles because of alloy shortages. The once-overheated war economy is visibly cooling, showing what happens when political ambition outruns industrial capacity.

The slowdown in one sector ripples through others, as less steel means fewer tank hulls, fewer engines mean stalled assembly lines, and fewer optical systems means tanks that roll out incomplete. Russia’s defense industry is interconnected, so a failure in any major factory cascades across the supply chain. Ural-vagon-zavod’s cutbacks, therefore, hint at a broader production crisis, one that no emergency decree of forced overtime can fix.

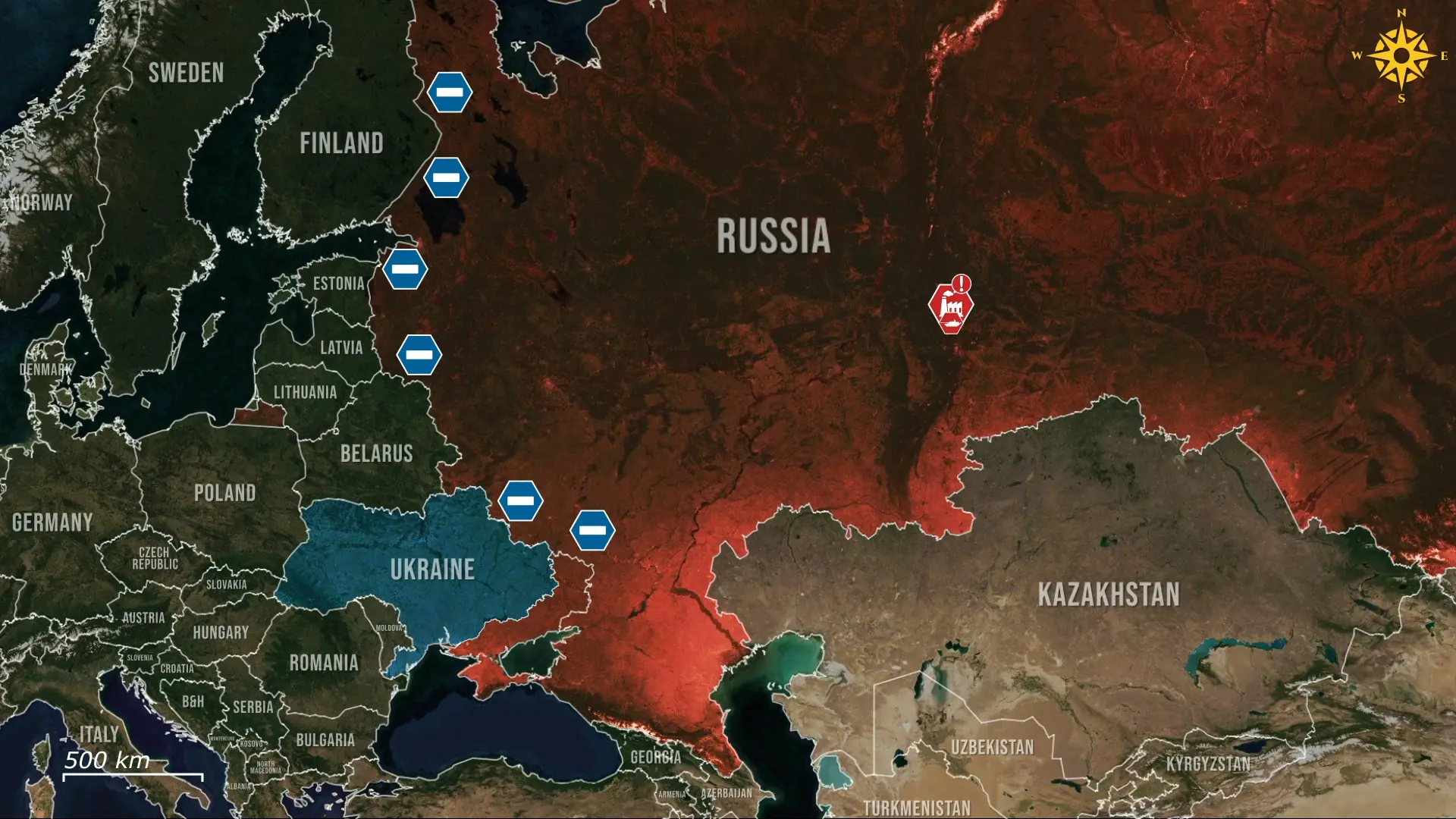

Overall, the layoffs at Ural-vagon-zavod are not just an economic footnote; they are a warning sign that Russia’s industrial war machine is reaching its limits. What began as a mobilization boom is turning into a contraction driven by exhaustion, shortages, and overextension. For Ukraine and its partners, this is a strategic opening; a weakened Russian industry cannot sustain a prolonged war of attrition.

The Kremlin can order new offensives, but if it cannot decree new factories or resurrect a workforce that no longer exists. The tanks that may keep rolling right now, but behind the frontline, the engine that builds them is beginning to fail.

.jpg)

Comments