Today, the biggest news comes from Ukraine.

Here, the flow of intelligence decides whether Ukraine reacts in time or gets hit blind and the cut off of its main source is becoming increasingly likely. Europe now claims it can take over the intelligence role, a shift that could redefine how this war is fought and how much risk Ukraine is forced to absorb.

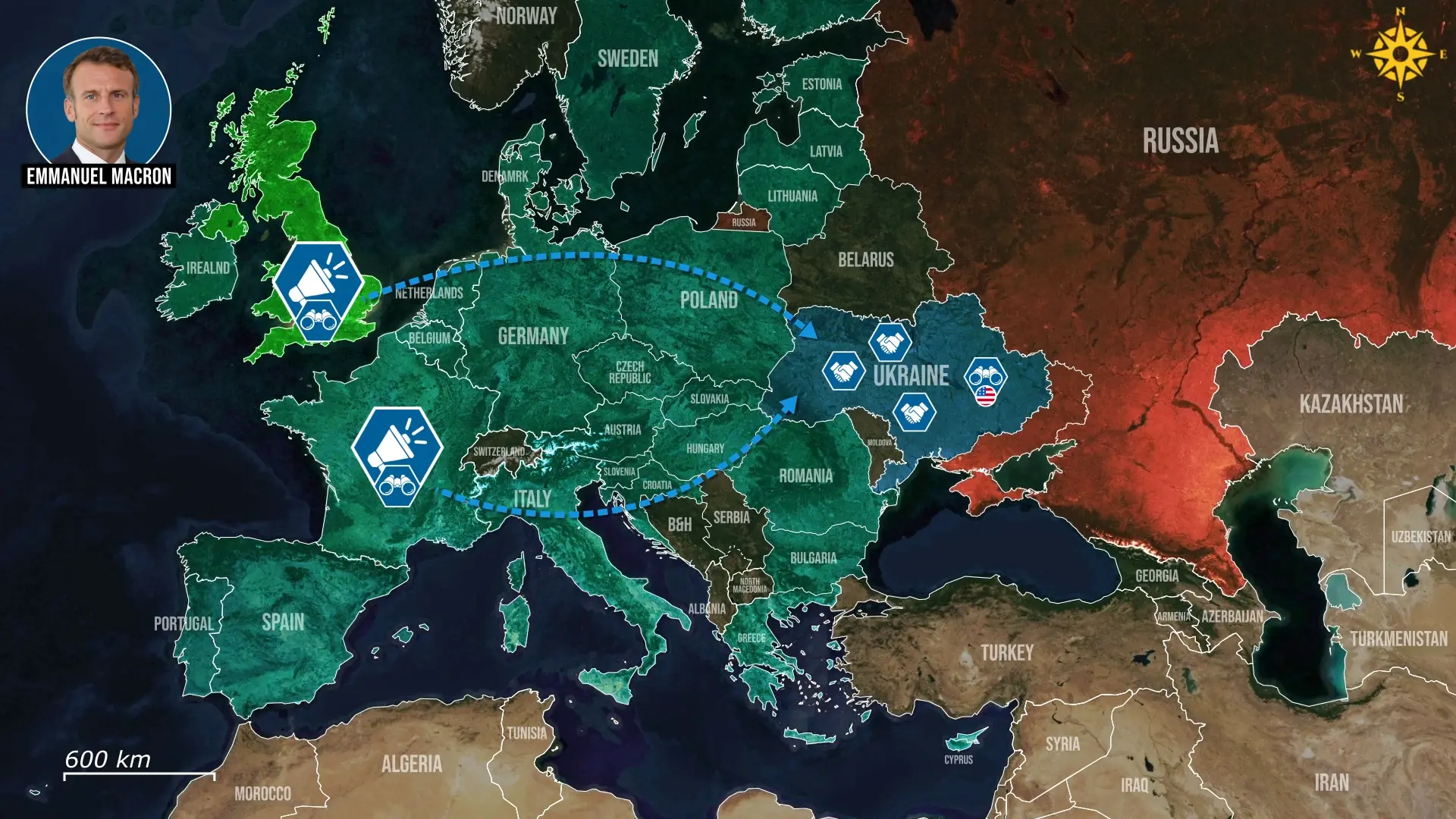

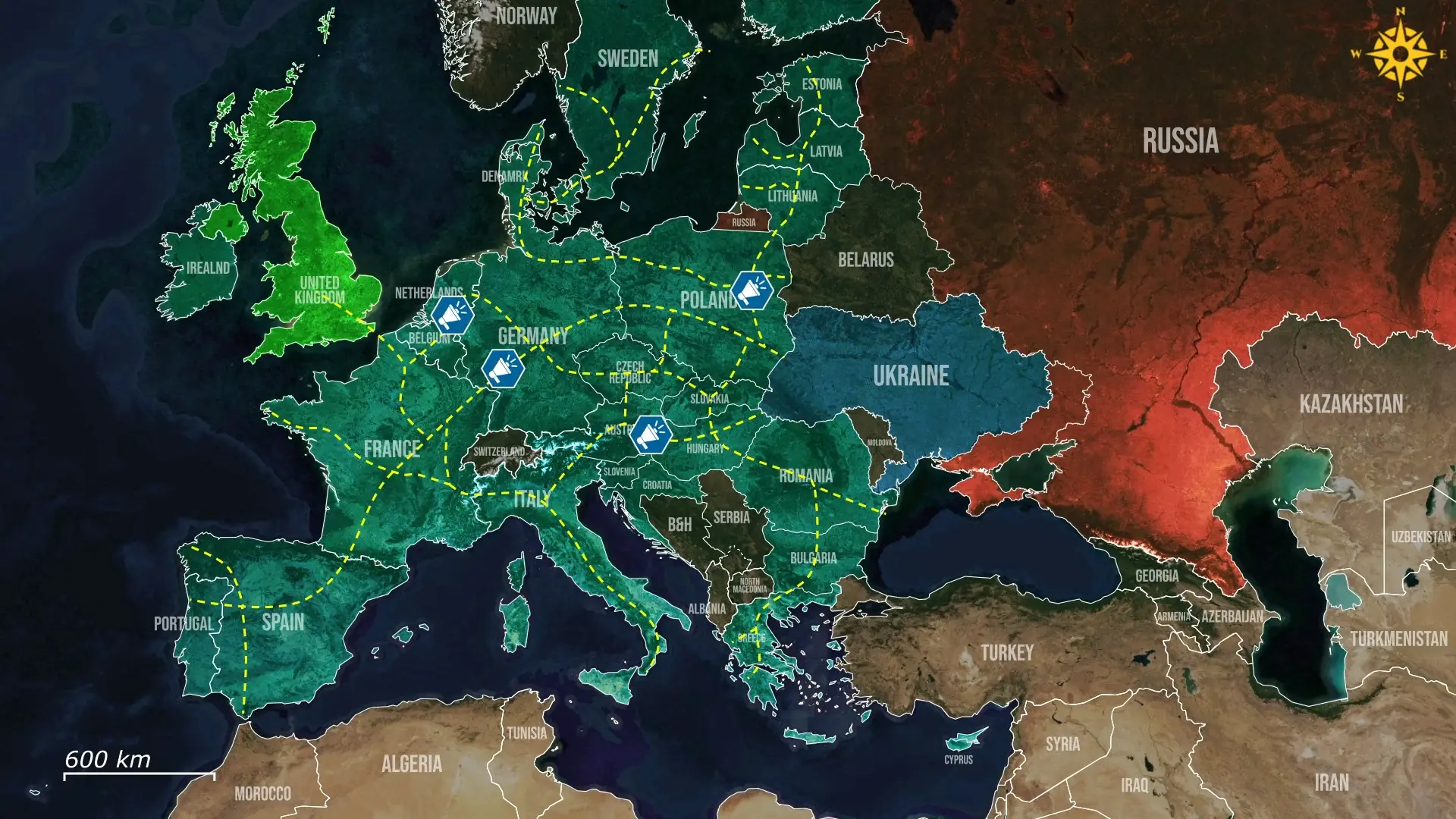

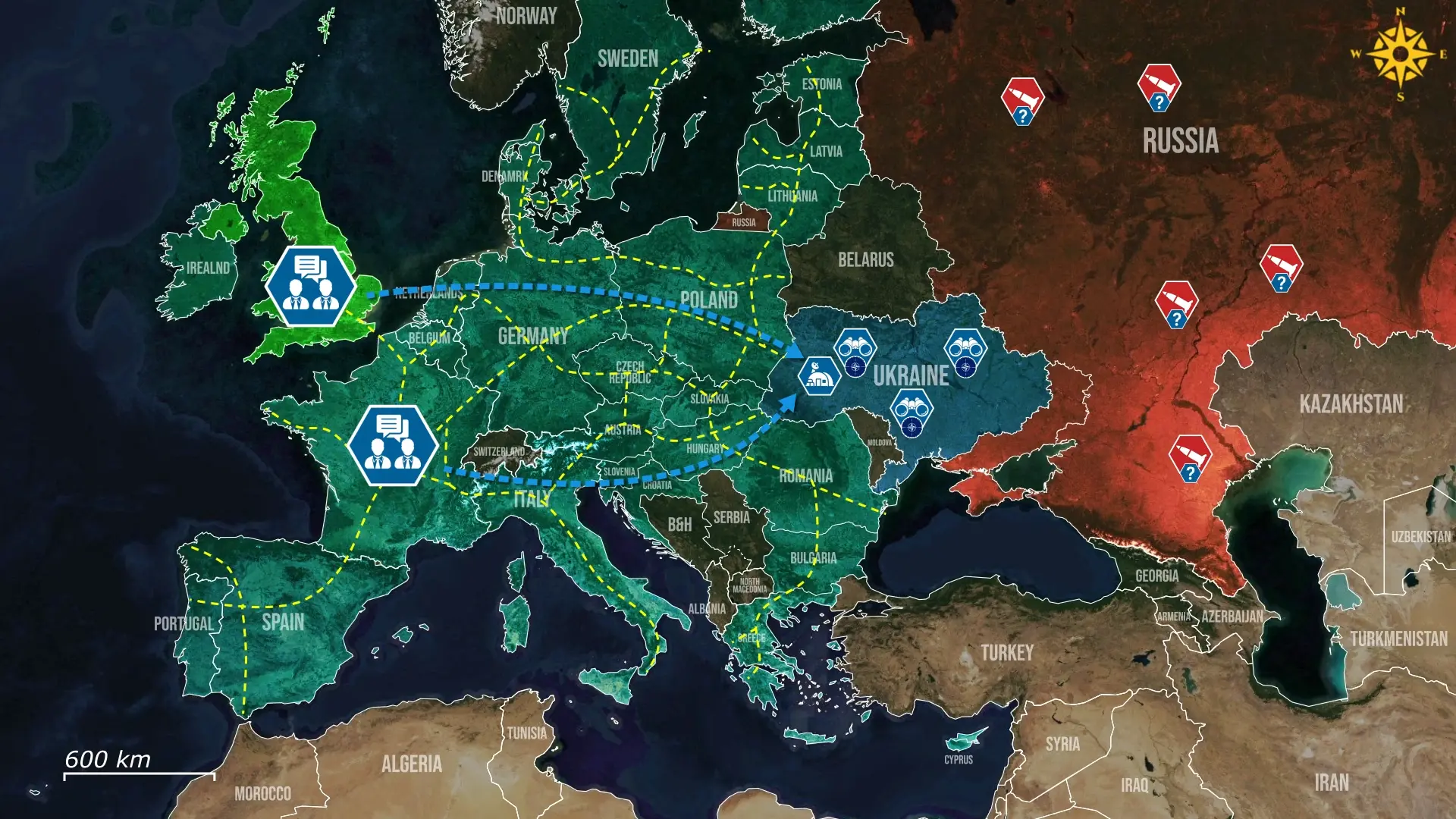

France and the UK have announced that they could take over the intelligence-sharing role for Ukraine within a matter of months. This claim comes as uncertainty around continued American support has pushed European governments to prepare for a smaller US role. France’s president Emmanuel Macron reinforced that position by stating that France alone is already providing roughly two-thirds of the intelligence Ukraine receives. Some officials also warn that dependence on external intelligence could be treated as leverage in negotiations, turning what is meant to be wartime support into a vulnerability that others may seek to exploit. This shift is presented as part of a broader European Coalition stepping into a role that was once dominated by the United States.

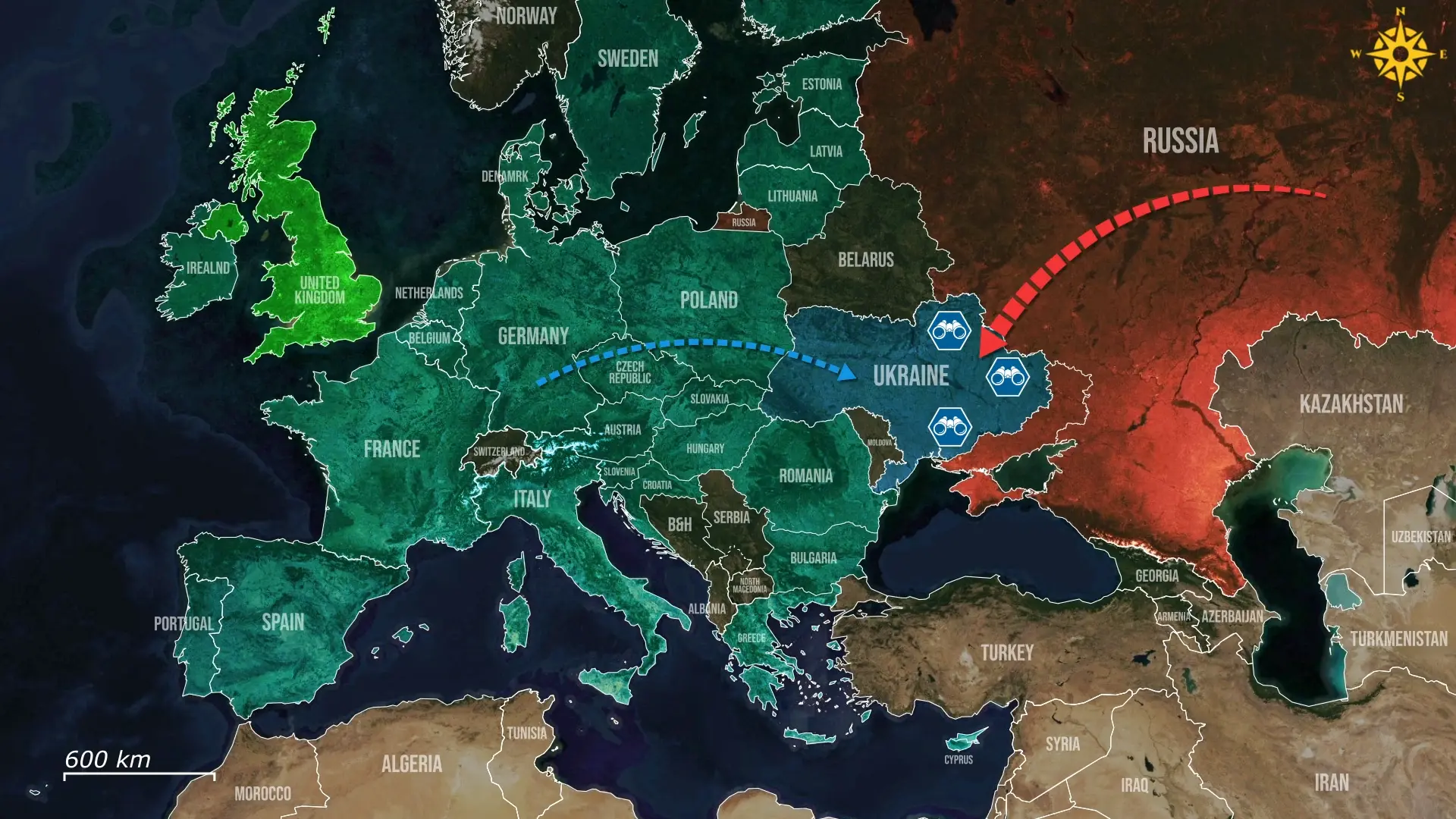

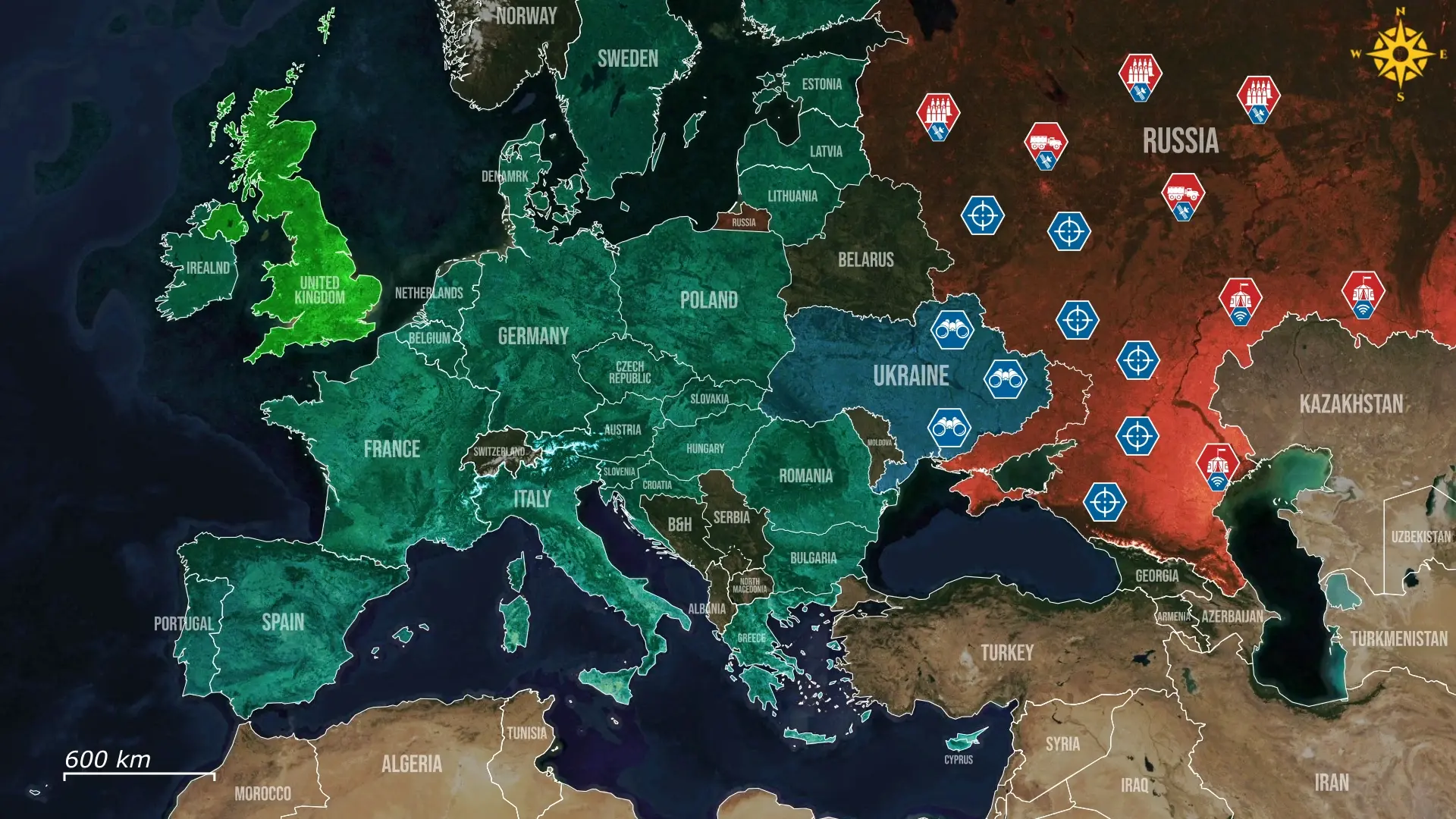

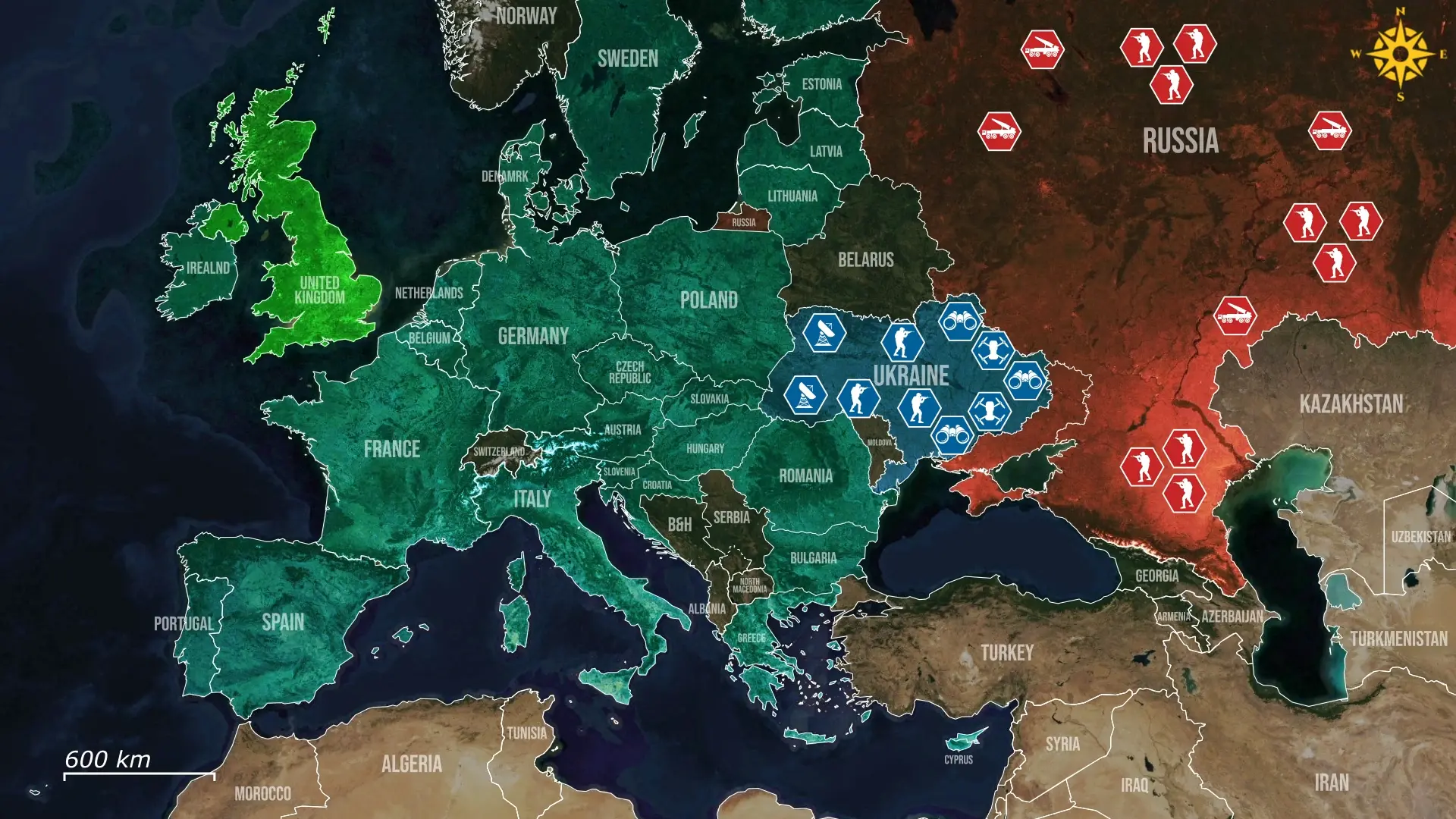

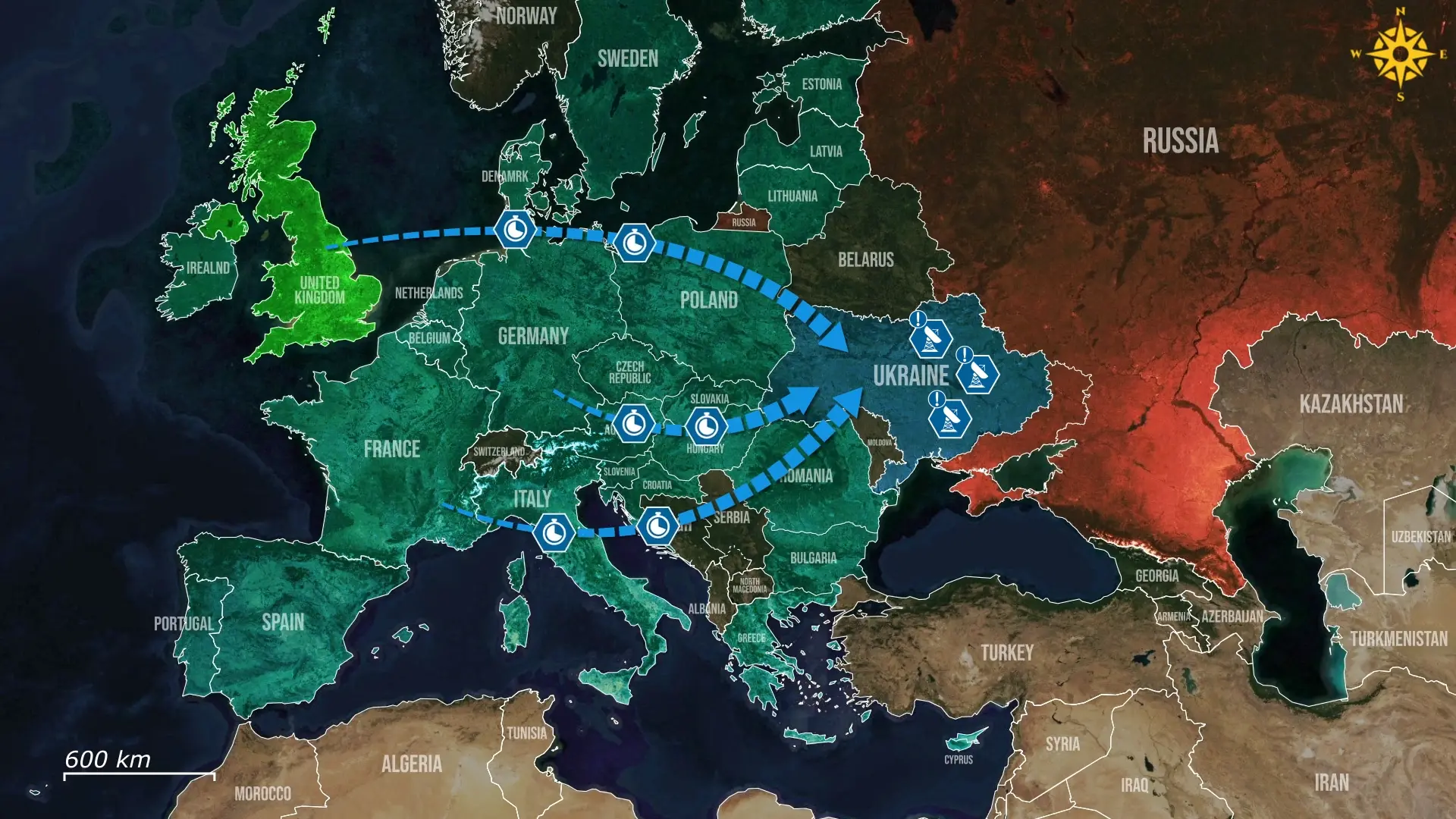

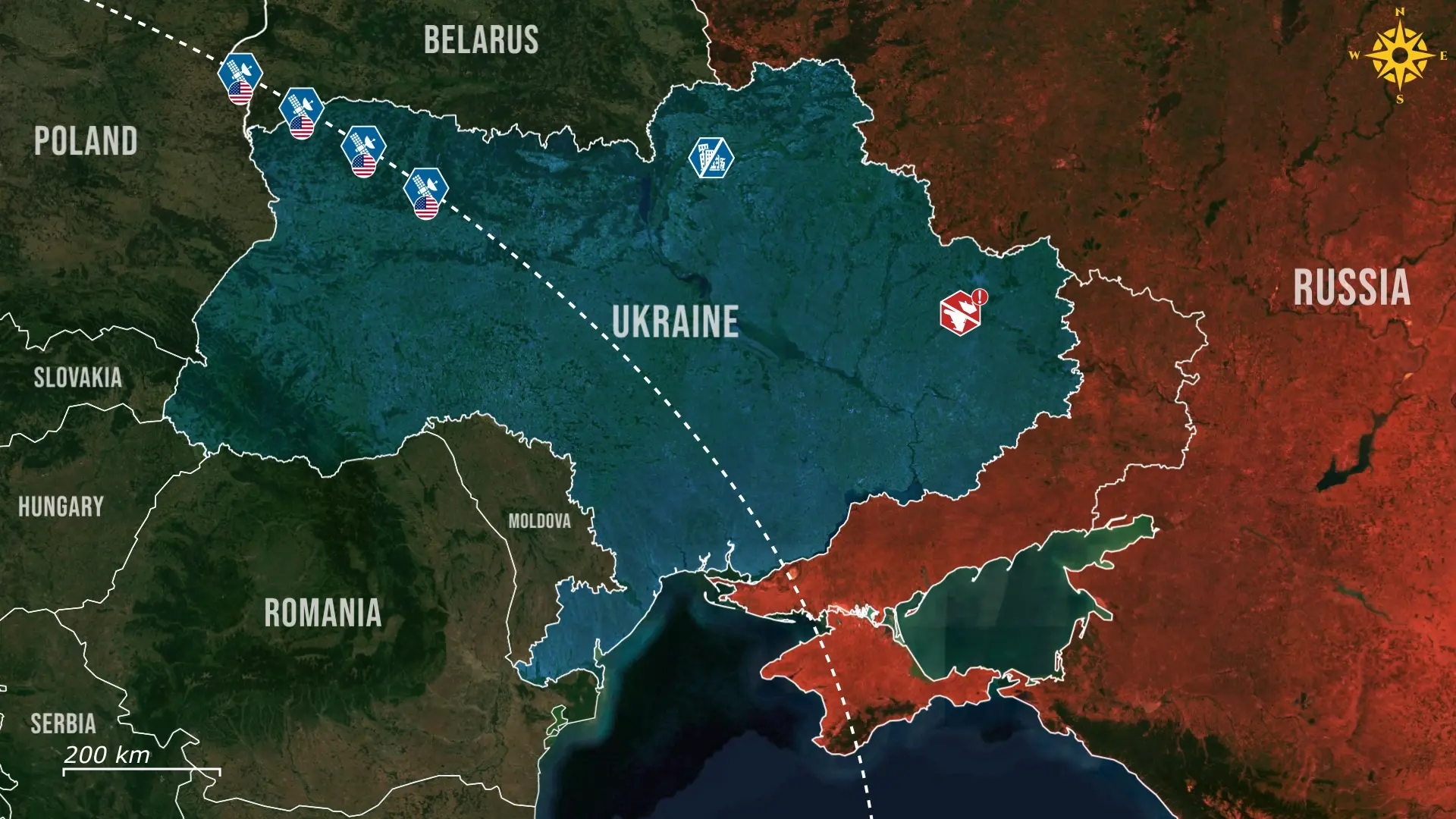

American intelligence support connects long-range sensing with operational decision-making, translating raw data into usable battlefield information. Satellite observation repeatedly scans areas far behind the front, helping analysts detect force build-ups or logistics changes that warn Ukrainian commanders where and when a Russian operation may be forming. Signal monitoring helps identify active command centers by detecting military communications, creating opportunities to disrupt coordination ahead of major operations.

The same monitoring can map active air-defense radars, allowing planners to route drones or missiles around protected areas and reduce exposure. Troop and targeting intelligence narrows this picture to specific locations and timing so Ukrainian forces can plan strikes or avoid threats. Early air-threat warning alerts Ukrainian forces for incoming missiles or drones, giving air defenses and civilians time to react.

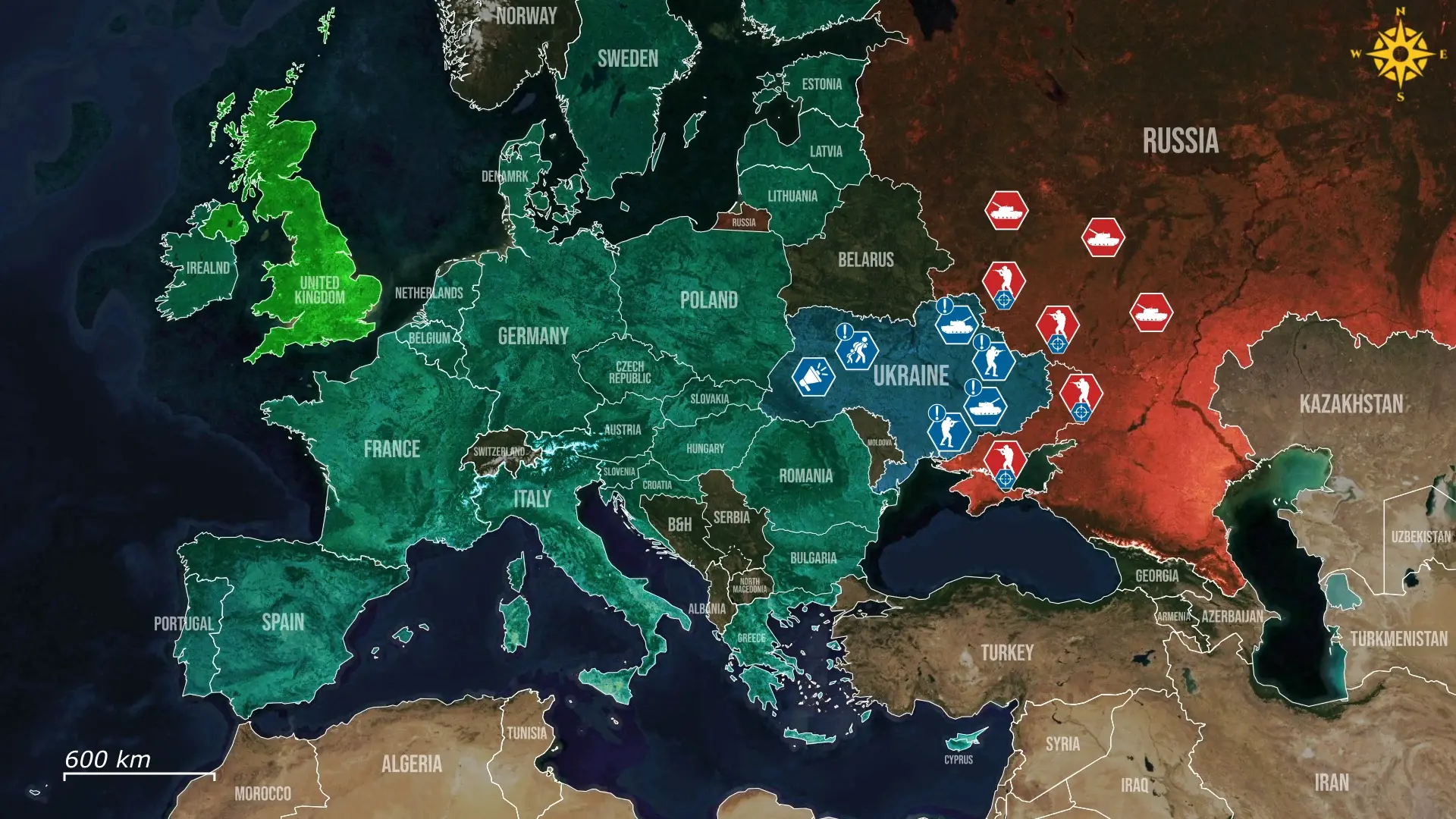

Ukraine already produces much of its own intelligence, especially close to the battlefield. Drones, local observation, and radars give Ukrainian forces a strong awareness of nearby threats. The limitation appears when Ukraine needs wide-area visibility from long distances, such as for detecting missile launches or troop build-ups behind the front, as those tasks depend on satellite networks that Ukraine does not fully have.

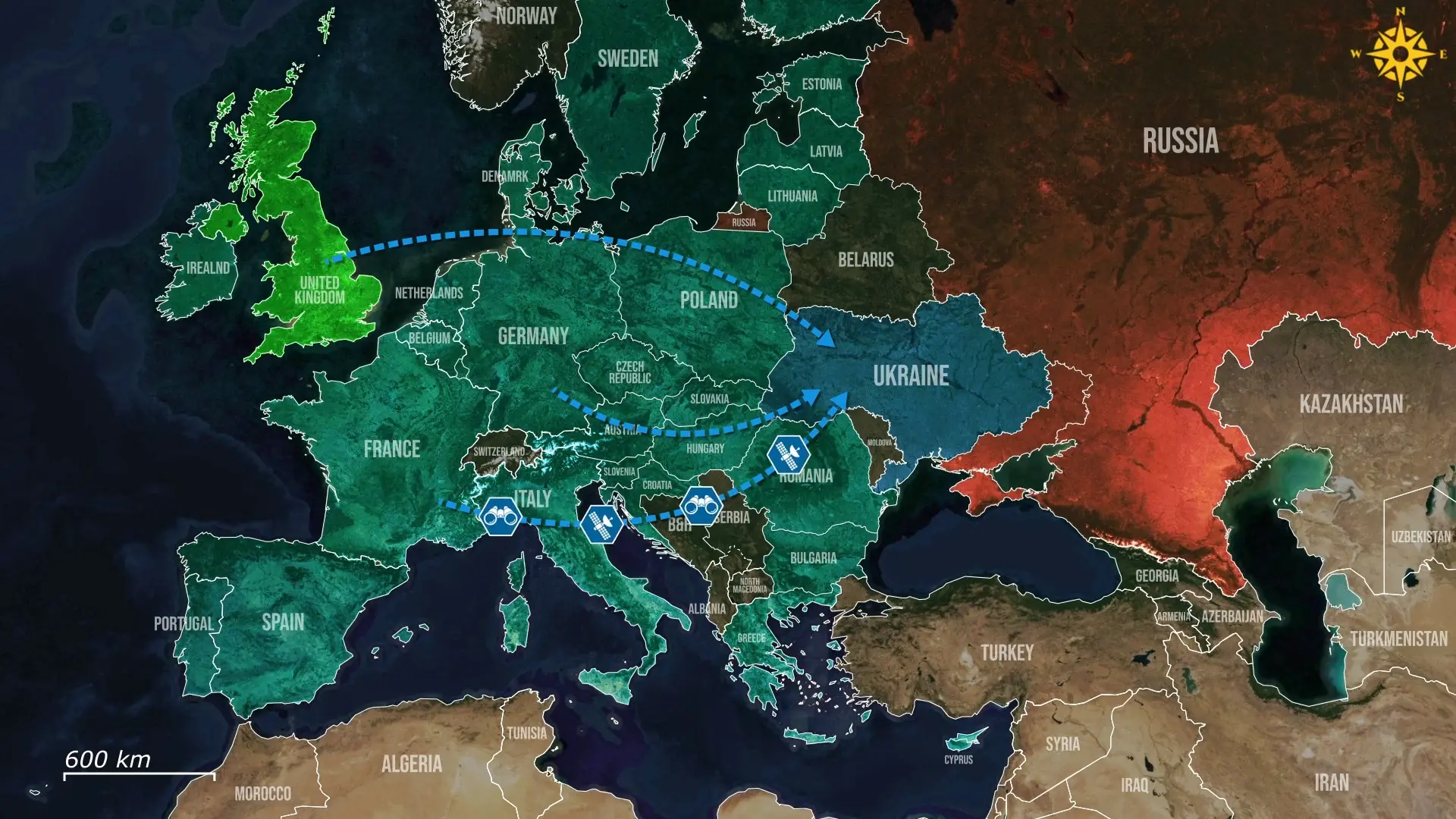

Europe’s ability to step in depends on covering enough of these same intelligence functions that the US provided. France contributes heavily through its intelligence-sharing infrastructure, providing satellite imagery and processed assessments that support Ukrainian planning. The United Kingdom adds strong signal monitoring and operational analysis, helping identify active radar networks and shifts in enemy communication patterns ahead of major Russian operations.

Nato contributes a broader surveillance framework that improves regional situational awareness and helps coordinate information flow among allies. Together, these capabilities allow Europe to deliver crucial information that supports Ukrainian planning and air-defense decisions, preserving many of the early-warning and assessment functions Ukraine relies on.

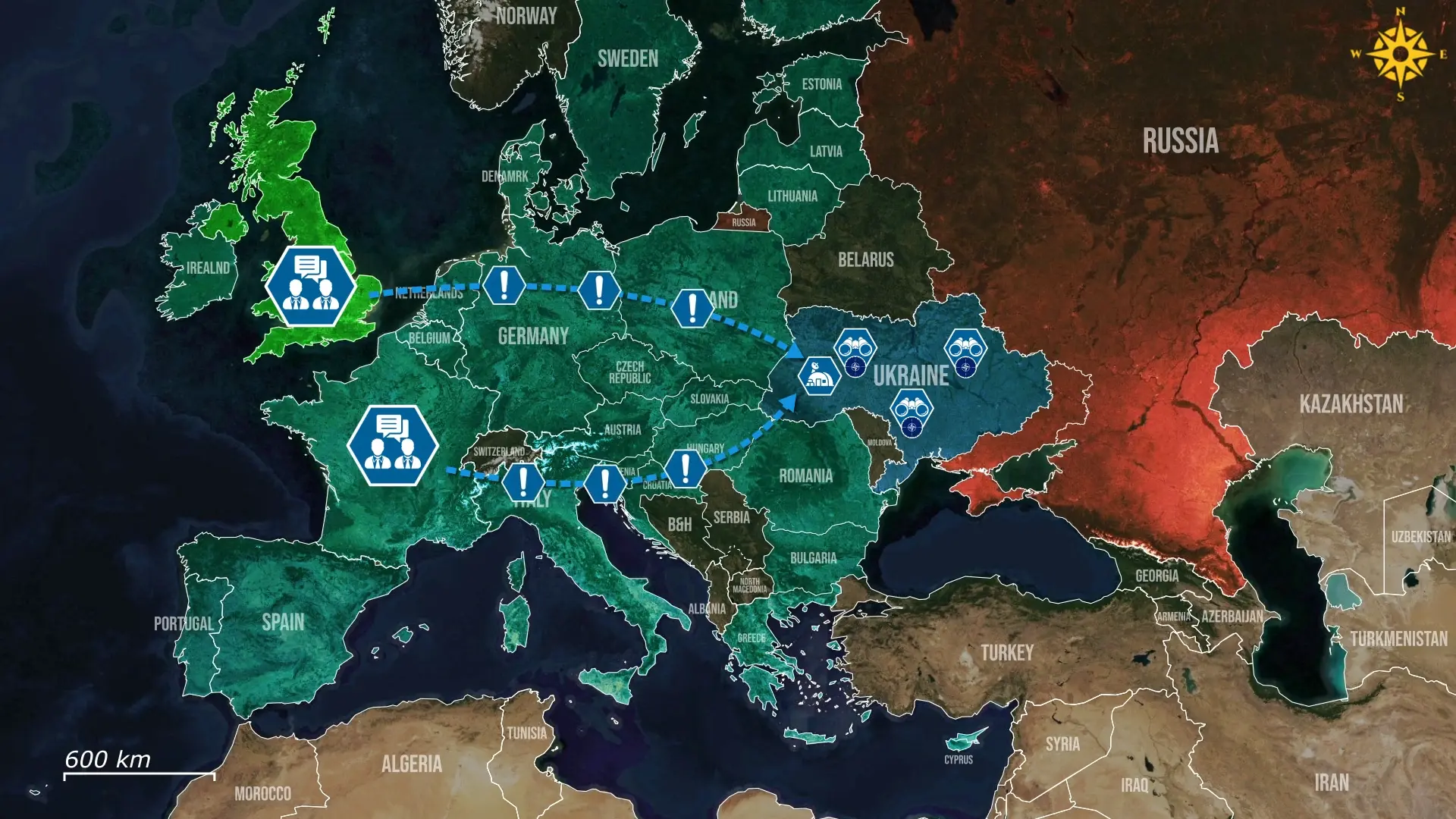

Replacing the US role therefore means rebuilding the same intelligence chain step by step rather than simply copying American infrastructure. Europe can expand satellite tasking to maintain coverage beyond the front, but satellite up-time and processing capacity are limited, which affects how quickly imagery becomes usable. European signal-monitoring assets can track active radar and command emissions, yet those inputs must be coordinated and fused across partners before they translate into operational insight.

Shared analysis teams convert that data into clear assessments, but this depends on secure exchange, trained personnel, and rapid interpretation under pressure. Delivery channels must then move those assessments into Ukrainian command posts quickly enough to influence interceptor timing, force positioning, and civilian warnings.

The hardest gap remains early missile warning and rapid data fusion, as those systems rely on constant sensor coverage and processing that cannot be expanded quickly. Taken together, these steps show that replacing the US role depends on sustaining a coordinated intelligence chain where timing and integration determine real operational effect.

Overall, the core issue is whether Europe can sustain the intelligence flow that Ukraine relies on in combat. Europe already has enough capability to assume a larger role through coordinated sharing, making a transition within months realistic if the goal is to keep core functions running rather than recreate the full American system. If the United States withdrew completely, the greatest strain would fall on early-warning systems that determine Ukraine’s reaction time to incoming missile strikes. The outcome depends on whether Europe can integrate and deliver intelligence fast enough to preserve that reaction advantage.

.jpg)

Comments