Today, the biggest news comes from the Russian Federation.

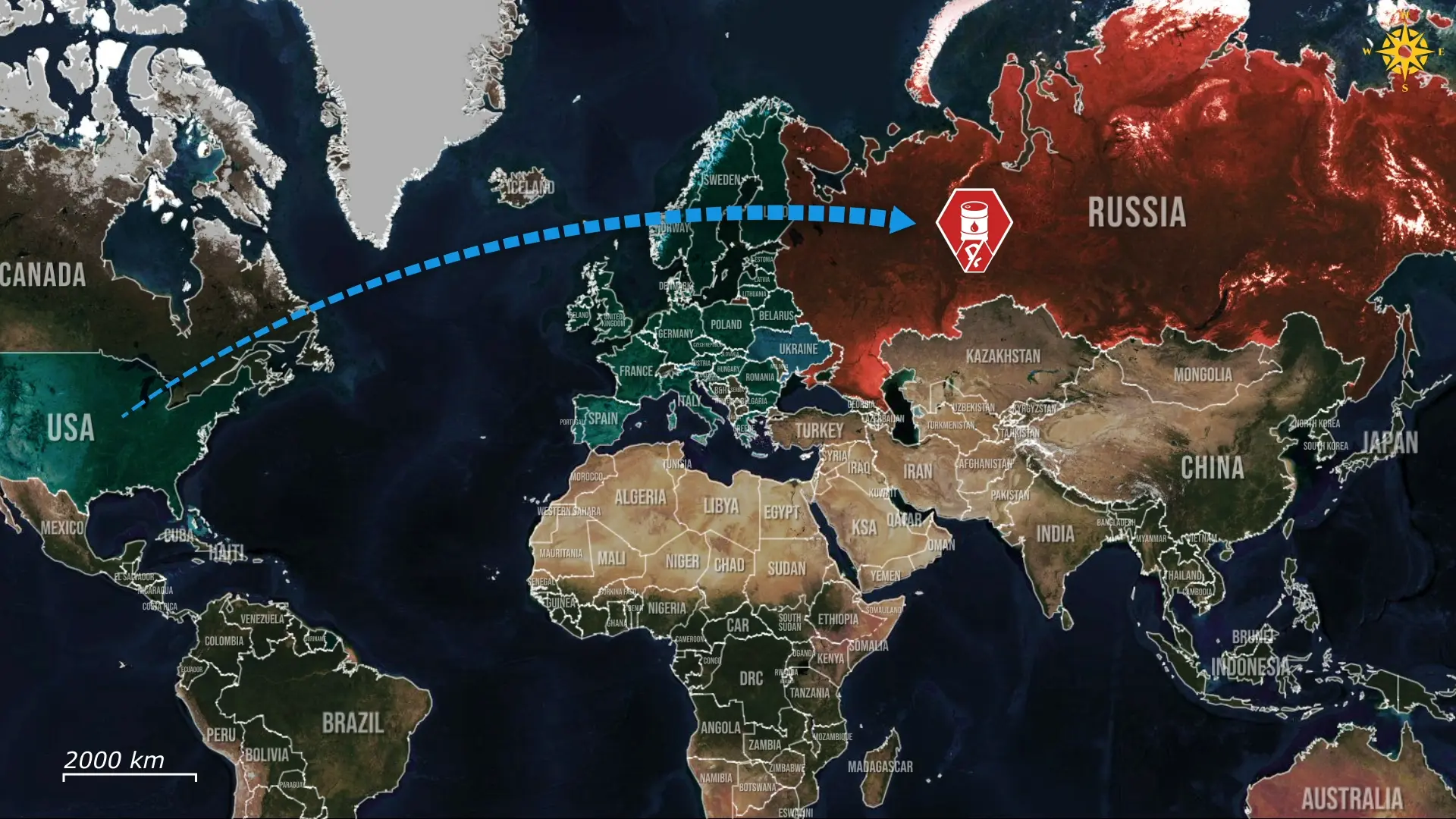

Here, Russian biggest oil companies have given up, with Lukoil announcing it will sell all of its foreign assets after fresh United States sanctions made continued operations abroad impossible. The decision, made within a week of new blocking measures, shows how even Russia’s largest privately run oil major can no longer shield itself from the tightening ring of financial restrictions.

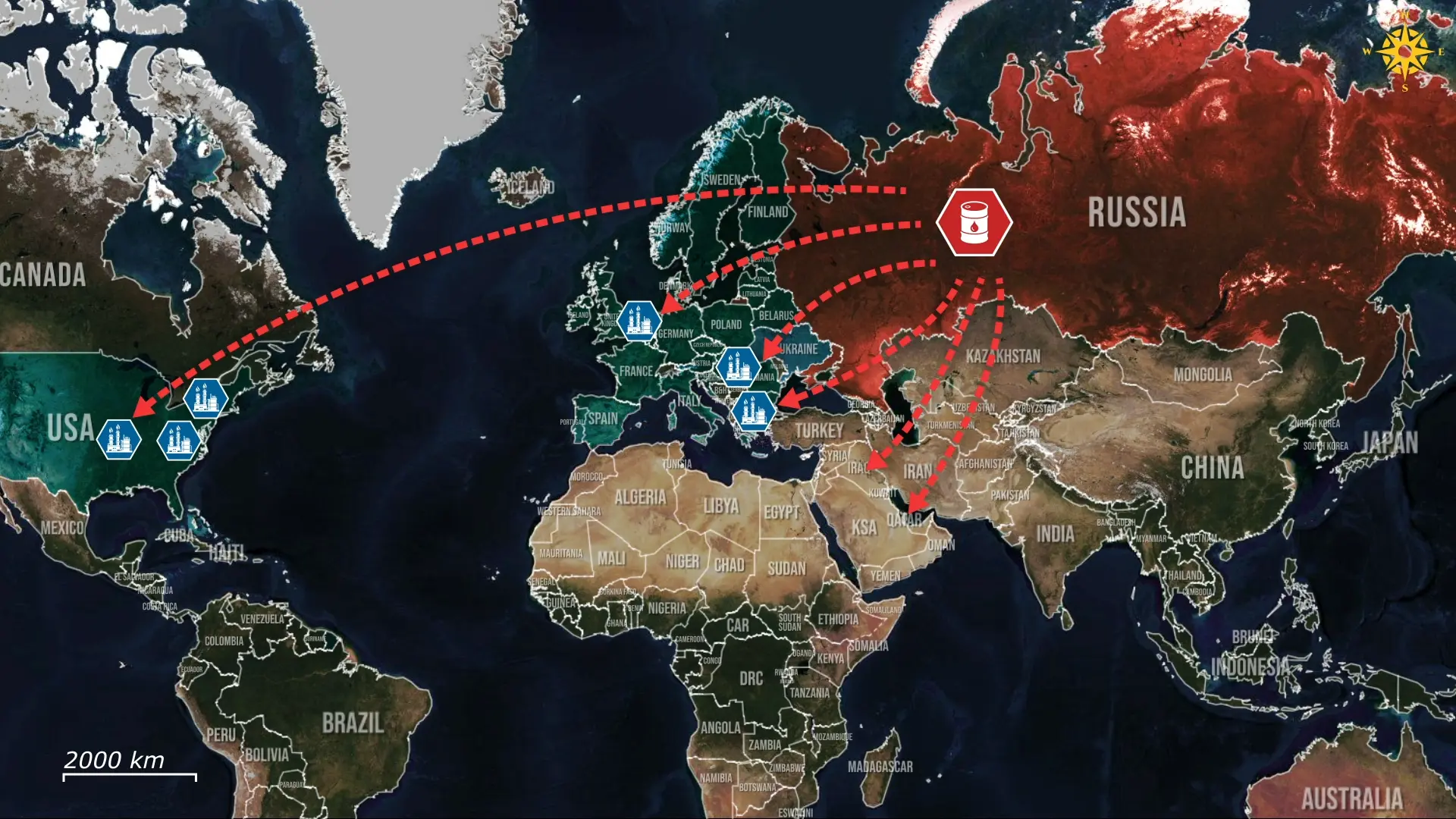

For Lukoil, this marks the end of three decades of global expansion, as the company will offload its service and distribution networks in the United States, its refining assets in the Netherlands, Romania, and Bulgaria, and its oil production ventures in Iraq and the United Arab Emirates. The scale is enormous, as the Neftochim Burgas refinery in Bulgaria alone handles close to ten million tons of crude a year, while the Petrotel plant in Romania and the Zeeland refinery in the Netherlands bring the company’s total European capacity to nearly fifteen million tonnes annually, giving Lukoil one of the largest foreign refining portfolios of any Russian oil major, giving Lukoil one of the most extensive refining footprints of any Russian company in Europe. In the United States, Lukoil built a sizeable network of stations in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania that generated stable dollar income even as sanctions hit other sectors.

Together, these assets formed a hard-currency lifeline that helped the company sustain production and modernize refineries inside Russia.

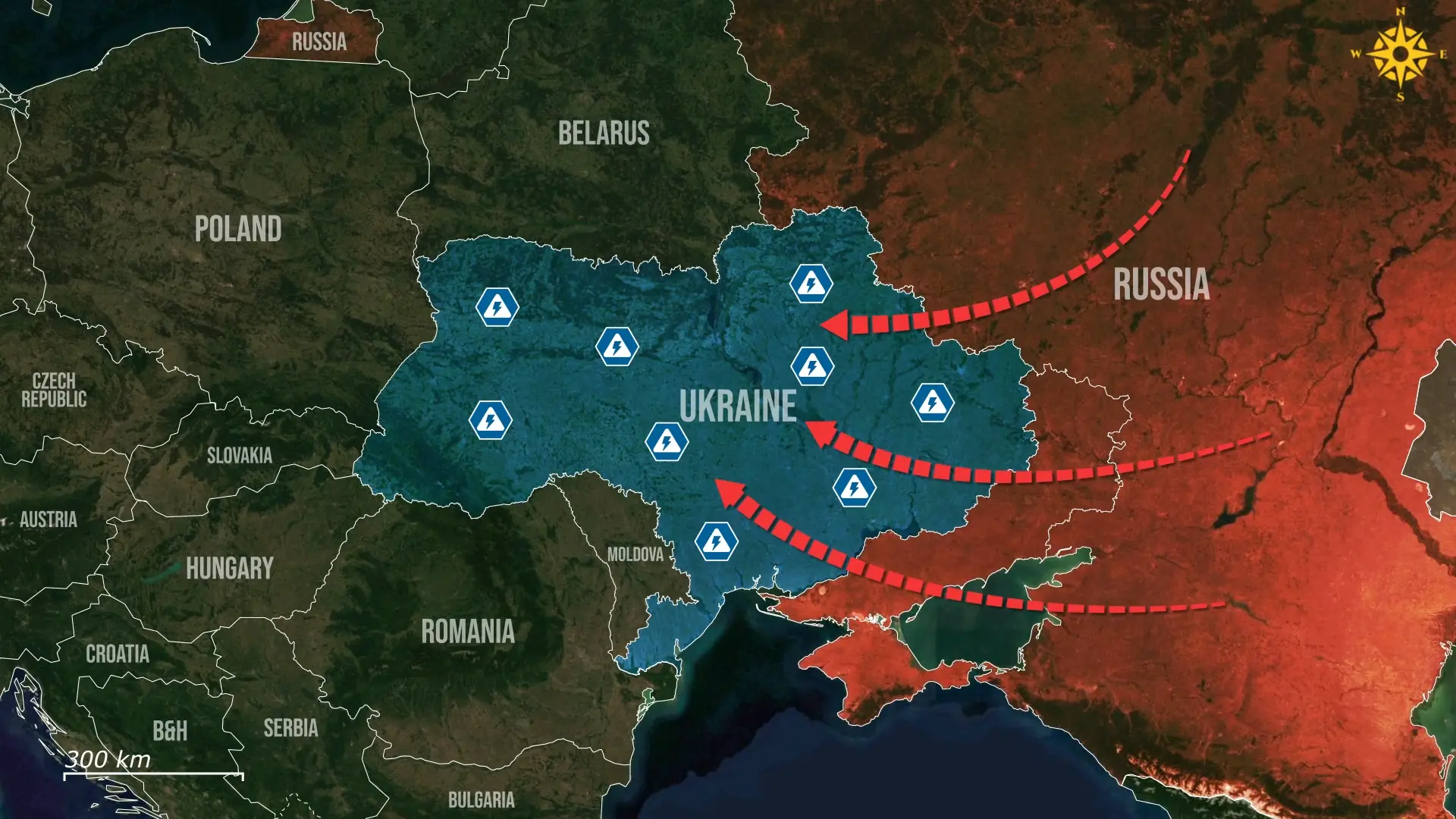

At home, Lukoil remains one of the cornerstones of the Russian oil industry. Its upstream fields in Western Siberia, the Tiam-Pechora basin, and the Caspian shelf feed five domestic refineries, Nizhny Novgorod, Volgograd, Perm, Ukhta, and smaller regional plants, that together process tens of millions of crude barrels each year. These facilities supply diesel, aviation fuel, and lubricants that directly support Russia’s wartime logistics. The loss of overseas refining and retail operations does not halt that output, but it removes an external cushion; fewer outlets abroad mean less flexibility to blend, store, and sell products in non-sanctioned markets, tightening the financial loop around the company’s exports.

The trigger for this sudden retreat was the new package of the United States Treasury sanctions issued in late October, which placed Lukoil and its subsidiaries under full blocking status. The order froze dollar and euro transactions and gave a one-month window for Western partners and counterparties to wind down contracts with Lukoil before sanctions took full effect. In practice, that deadline is meaningless, as Western bank insurers and shipping firms withdraw immediately once a company is blacklisted, leaving it unable to move funds, insure cargo, or even pay staff in foreign jurisdictions.

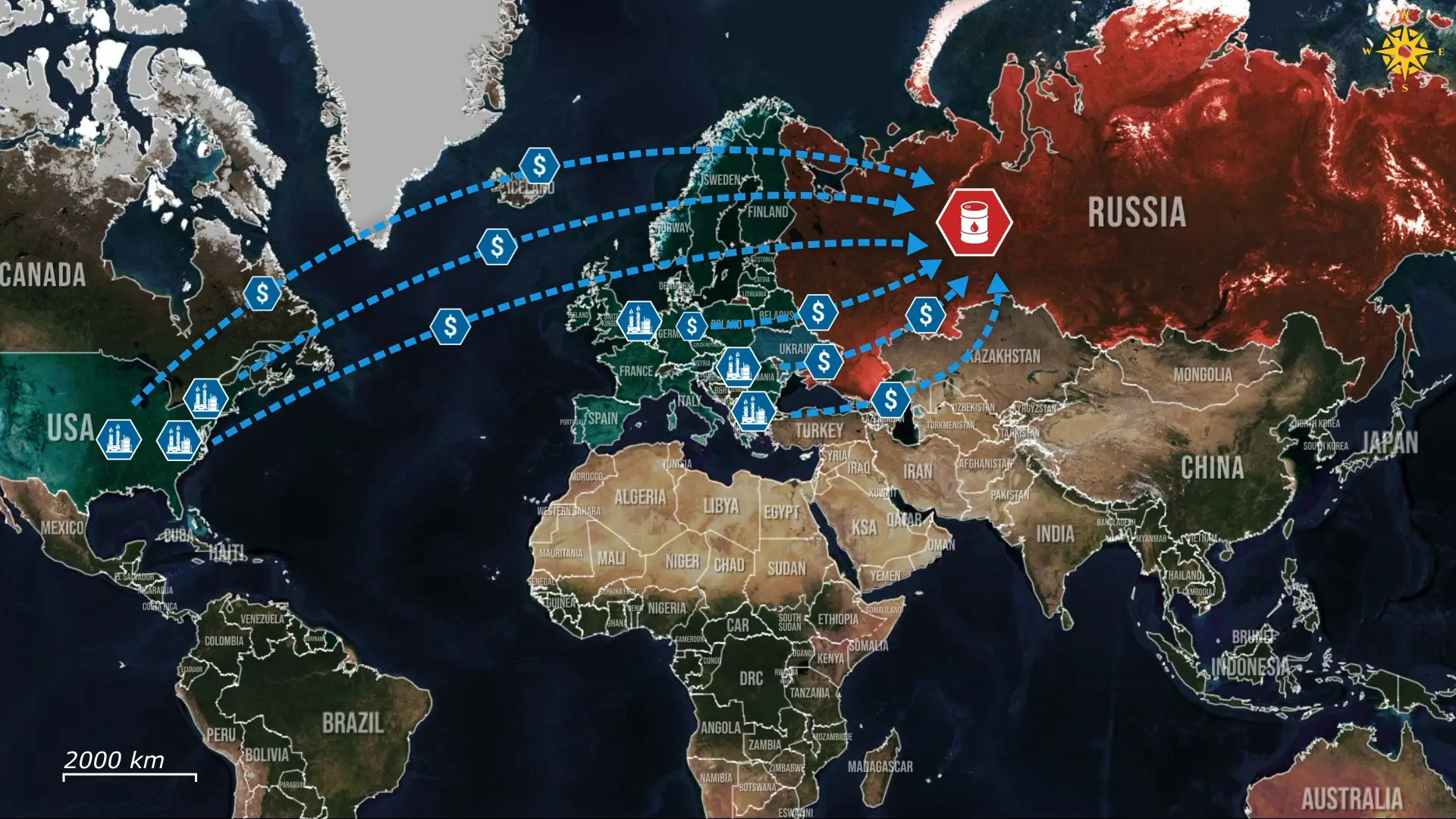

As a result, the share price fell more than twelve percent in four trading days, and potential buyers are well aware that the company must sell at a discount, leaving it little leverage for negotiations. For a refinery such as Burgas, a typical margin of ten dollars per barrel on roughly sixty million barrels a year implies over half a billion dollars in annual gross profit. Factoring in all of Lukoil’s foreign assets, from its retail networks in Europe and the United States to refining and upstream projects in the Middle East, the company has lost access to an estimated four to five billion dollars in revenue almost overnight.

The sale’s aftermath will ripple through the Russian energy system, as losing its Balkan and European hubs means cutting off billions in export income and forcing fuel exports onto longer, riskier routes through intermediary traders and the shadow fleet, where freight and insurance costs can rise by 30 to 40 percent.

Fuel once refined and sold in Europe now has to be processed and marketed domestically, pushing already strained plants in Nizhny Novgorod, Volgograd, and Perm to their limits. The disappearance of steady hard-currency revenue from foreign retail and storage networks leaves a cash shortfall that may reach four billion dollars a year, even as maintenance costs for complex refineries climb. Lukoil will likely redirect parts of its capital toward new ventures in the Gulf and Asia, but those projects are years from profitability and operate under different political and logistical risks.

Overall, Lukoil’s decision captures how far sanctions have eroded the foundations of Russia’s private oil sector. The company is not collapsing, but it is retreating into a smaller, less connected one that relies on barter deals, longer supply chains, and domestic financing. What once was Russia’s most globally integrated energy major is turning into a regional operator constrained by liquidity in the short term, but it strips away its international footprint that gave Lukoil resilience and reach. In the long run, this retreat signals a shrinking Russian energy sphere, one that is less competitive abroad and more dependent on state backing at home.

.jpg)

Comments