Today, the biggest news comes from Europe.

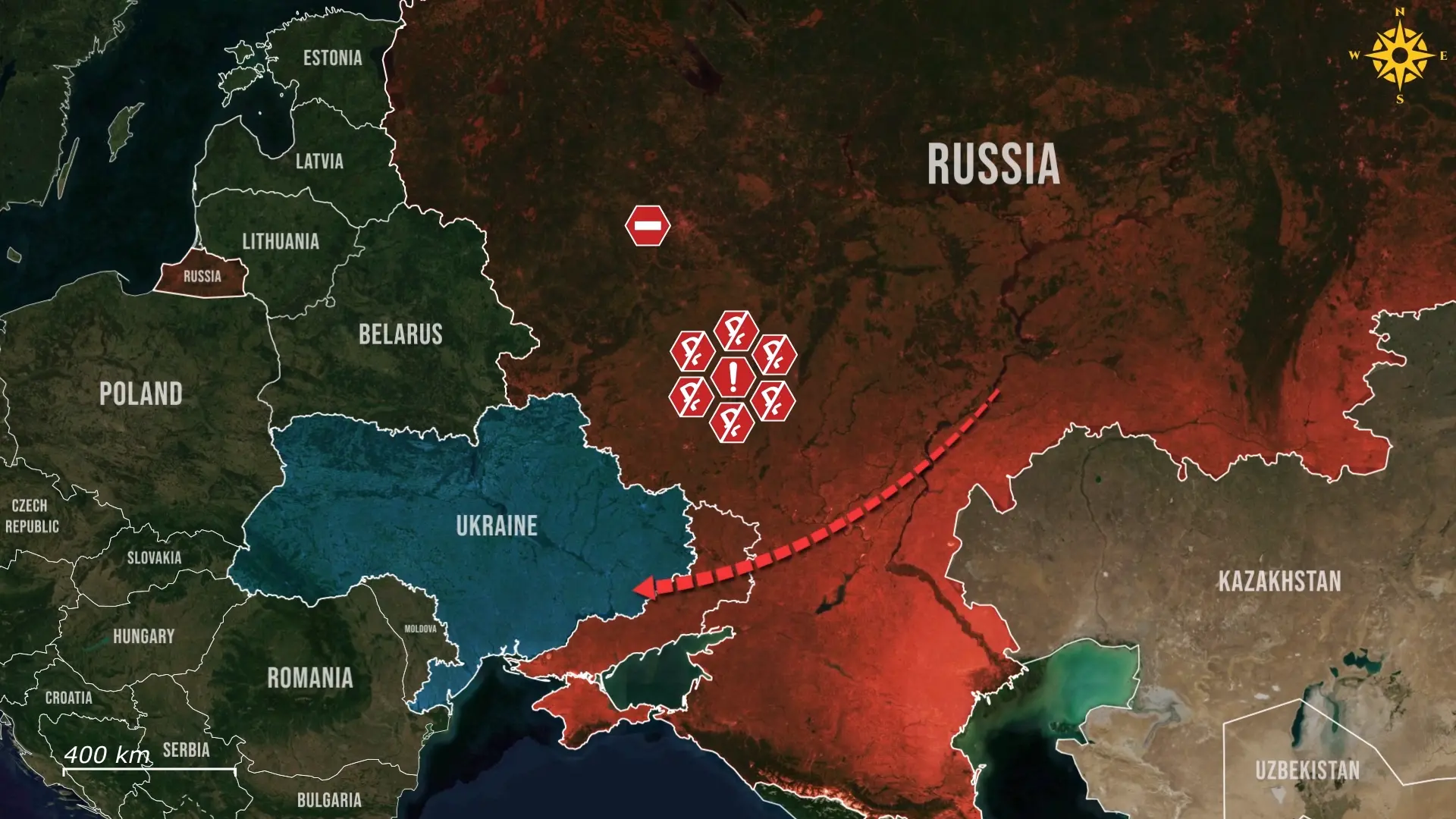

Here, governments across the continent are preparing to seize or nationalize Russian-owned energy assets after new U.S. sanctions forced Lukoil to liquidate its foreign holdings. What began as one company’s retreat has escalated into a continental shift, with governments from Berlin to Belgrade facing the same question, whether to risk sanctions or expropriate Russian fuel infrastructure outright.

The new sanctions from Washington are among the most consequential to date, as they target any European entity still cooperating with Russian oil subsidiaries, making continued operations legally risky and financially impossible. If you remember from previous reports, Lukoil was the first casualty, forced to sell its refineries in Bulgaria, Romania, the Netherlands, and the US. The company’s European footprint once accounted for billions in revenue, but its rapid withdrawal set a precedent; every Russian-controlled refinery and distributor in Europe is now under review. To avoid secondary sanctions, governments are drafting emergency measures ranging from nationalization to forced sales.

Germany is the most consequential case, as Berlin is considering full nationalization of Rosneft Deutschland, which controls the Schwedt and Karlsruhe refineries, facilities responsible for roughly one-fifth of Germany’s fuel supply.

The company has been under government trusteeship since 2022, but the new sanctions are prompting the government to consider permanent state ownership. Officials argue the move is necessary to protect security and prevent a key node in the supply chain from falling into financial paralysis. Schwedt alone fuels the capital and large parts of Eastern Germany. Any disruption there would risk shortages, protests, and political backlash.

In Serbia, the crisis is even more severe, as the national oil company NIS remains 56 percent owned by Gazprom-linked entities and now faces U.S. secondary sanctions. The Treasury Department suspended its access to international banking and warned that supplies through Croatia’s Janaf pipeline will stop unless Russian ownership is resolved. President Aleksandar Vucic has acknowledged that nationalization is a last resort but admits he may have no choice. NIS provides nearly ten percent of Serbia’s budget revenue, and its refinery in Pancevo will run out of oil within weeks unless a deal is struck. A shutdown would leave the country without fuel by winter, forcing Belgrade to choose between economic survival and its political ties to Moscow.

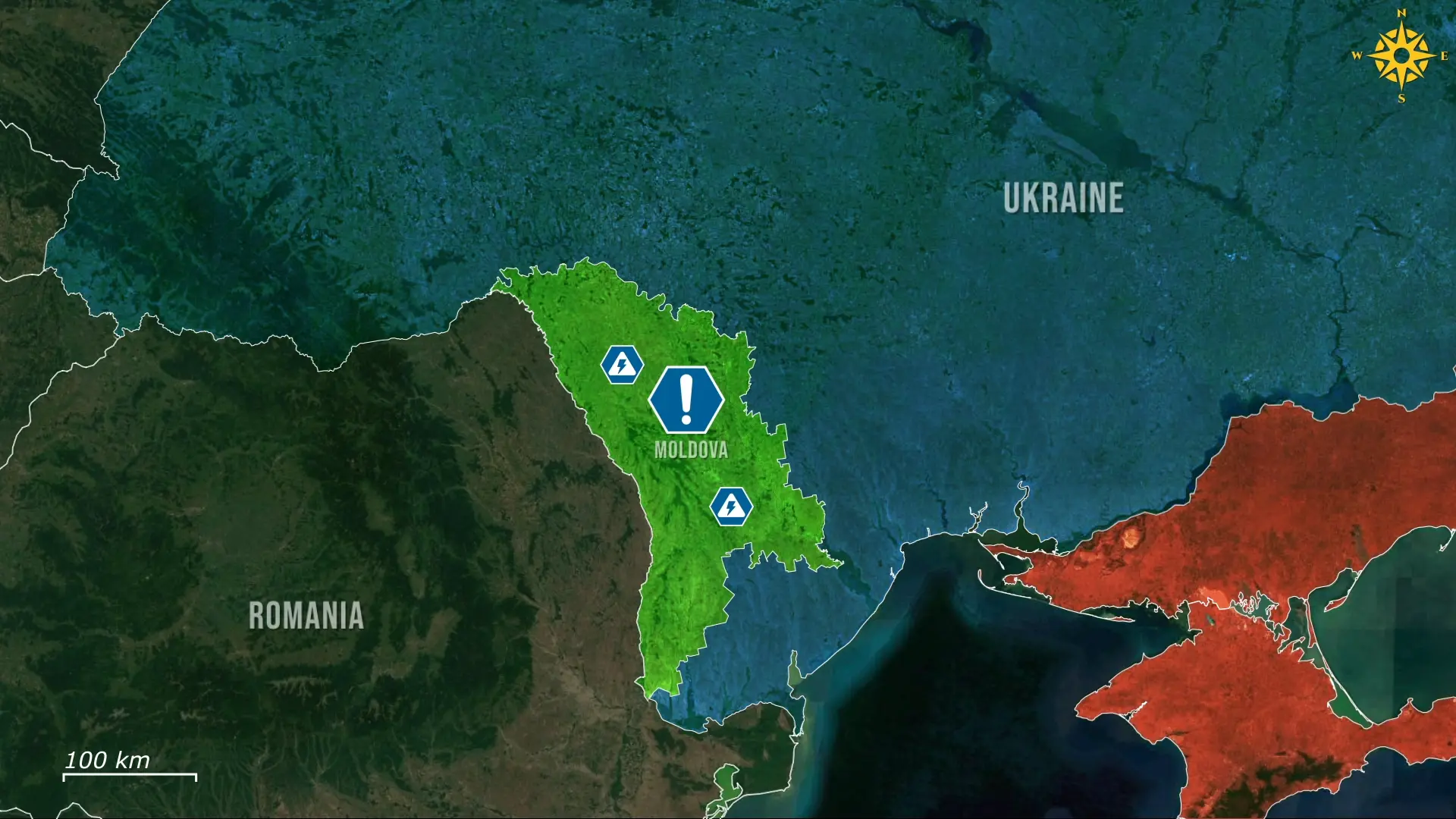

Bulgaria’s case follows a similar trajectory, with a strategic twist, as the Lukoil-owned Burgas refinery, which supplies about 80 percent of the nation’s fuel, was already being prepared for sale as part of Lukoil’s broader withdrawal from foreign assets.

Now, Sofia is moving to take advantage of the situation, positioning itself to buy the refinery, potentially at a steep discount, before new US sanctions freeze the deal entirely. The government has asked Washington for a temporary exemption to keep operations stable, warning that any halt could spark shortages and unrest. For years, Burgas symbolised Moscow’s economic foothold inside the European Union. Now it may become state property, acquired on Europe’s terms rather than Russia's.

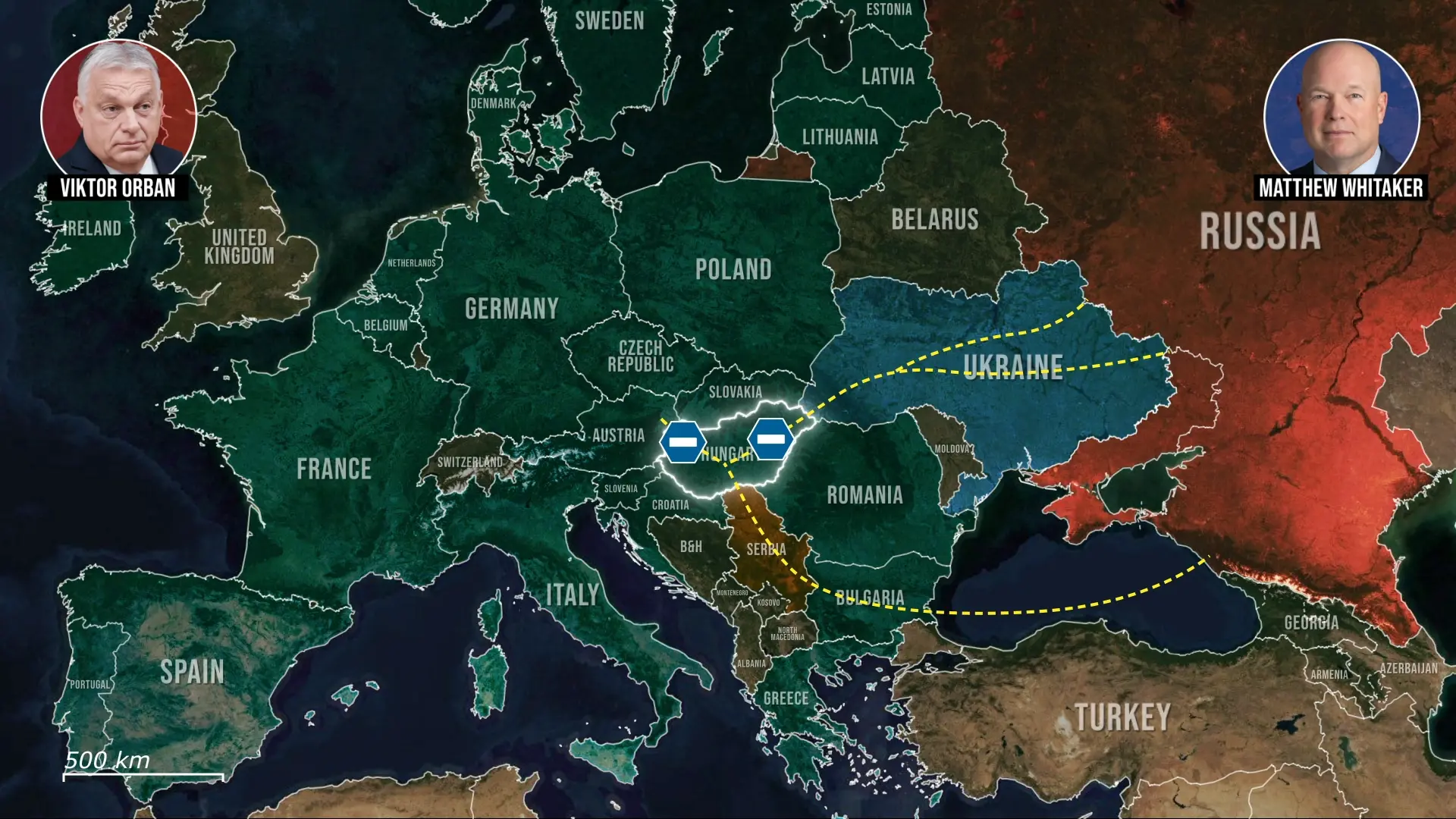

Hungary, by contrast, remains the most reluctant to act, because Prime Minister Viktor Orban continues to deepen energy ties with Moscow despite repeated warnings from Washington and Brussels. US envoy Matthew Whitaker stated that Budapest should not receive exception on the sanctions as pushed by Hungarian officials, noting that Hungary has taken no active steps to reduce dependence on Russian crude. Officials had even warned that the pipeline supplying Hungary with Russian oil will not remain open indefinitely. Instead of adjusting course, Oban’s plan was to meet Trump in Washington to seek protection from the sanctions regime, an appeal that highlights Hungary’s growing isolation within Europe’s energy policy.

For Europe, the wave of nationalizations represents a strategic consolidation of energy sovereignty. The last remains of Moscow’s energy empire, its refineries, storage sites, and retail networks, are being dismantled. Once viewed as vital links in a shared energy market, they are now treated as risks to national security. For Russia, the consequences are lasting, as companies like Lukoil, Rosneft, and Gazprom Neft spent decades expanding across the continent to gain political leverage and hard-currency revenue. That influence is evaporating almost overnight.

Overall, Europe’s nationalization drive marks the end of Russia’s decades-long dominance in its energy sector. Each seized refinery and dissolved partnership further isolates Moscow, transforming sanctions from financial pressure into a structural realignment, as Europe’s dependence has turned into control, while Russia’s former assets are becoming symbols of its retreat from the continent.

.jpg)

Comments